Internationally acclaimed Canadian bad-boy puppeteer Ronnie Burkett laughs when the discussion turns to Madam, the outrageously camp puppet creation of 1970s-era ventriloquist Waylon Flowers. “I loved Madam,” he exclaims. “At a certain point I contemplated going the Vegas route. I actually stood at the threshold – can you imagine? By now my face would be all pulled up and I’d look like Siegfried or Roy.”

There are so many roads one can take. But that was definitely not the route for Burkett, who has been dedicated to refining his craft for more than 30 years, ever since he was 14.

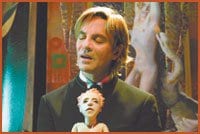

With his theatre company Ronnie Burkett Theatre Of Marionettes, the artist has created a series of full-length, adult puppet performances aimed at returning the puppet to the legitimate stage.

His long list of shows, including the early Fool’s Edge and Virtue Falls, all the way through the Memory Dress Trilogy (Tinka’s New Dress, Street Of Blood and Happy), have been critically successful around the world, and have garnered too many awards to list, including a special Obie and a GLAAD Media Award.

Burkett has carved a unique niche, and has earned the reputation for being one of the world’s leaders in puppetry.

Provenance, which has played several Canadian and European stages before its Ottawa engagement, opened Jan 13 at the Great Canadian Theatre Company.

“Provenance is a great word that’s used mostly in the art world now,” says Burkett. “It means ‘history of ownership.’ It sounds kind of religious, it has some mysterious import to it.”

The show is an exploration of beauty and objectification. “Everybody objectifies,” Burkett says. “And people who say they don’t are lying.”

When Burkett first began writing the piece he thought that the opposite of beauty was grotesque. But he came to understand that, instead, plain was on the other end of the spectrum.

“I think most of us on the planet are plain. We’re not grotesque, and we’re not so jaw-dropping beautiful that when we enter a room everyone gasps,” says Burkett, “even though that’s everyone’s fantasy. It’s certainly been mine.”

But he says that in all that plainness is actually where all the beauty can be found.

The idea for Provenance came in part from Burkett’s growing fascination with paintings. “If I could have my dream fantasy I would run away and be a painter.

“The story of Provenance revolves around a painting of a boy in green stockings leaning against a tree, with a swan. It’s a take on St Sebastian and Leda and the swan.”

The plot concerns a plain-Jane Canadian art student named Pity Beane who travels to Vienna, obsessed with the painting, which hangs in the brothel of an aged madam named Leda.

“So we have a static image, a two-dimensional thing, as the central character,” Burkett says. “And we have these two women on opposite ends of the age spectrum who are both obsessed with this thing for different reasons.”

In the play, as Pity learns more about the story behind the painting, her feelings toward it are changed. “A lot of times knowing the back-story of the thing or the person we are objectifying is detrimental,” Burkett says. “Knowing too much can interfere with your fantasy.

“On the other hand, if I knew the person who painted this thing,” says Burkett, gesturing to a bad painting on the wall, “was blind or dying of leukemia, I might like it more.” He sighs. “Or maybe not.”

Of course, Provenance is also populated by a colourful cast of Burkett-esque characters. It has elaborate settings, costumes and lighting, and an innovative head rig that allows the artist to move characters in new ways.

“This is the most exhausting piece I’ve ever done, and I’m quite surprised,” he says. “There aren’t more characters or props or costumes than usual. It’s just emotionally exhausting.”

He describes a long section that happens near the end of the show that is the revelation of Tender, the boy in the painting.

“It’s his entire story in eight single-spaced pages of text, and it’s in verse,” Burkett says. “Once I start, I must be totally committed, without stopping to wink or nod to the audience. It’s relentless and it’s brutal, and it’s amazing to do.”

Burkett trusts the good will of his audience to go with him for the ride.

“After they’ve come with me to that point, I think they know I won’t leave them in the dark,” he says. “There is a little arc to hope, but before we get there we must see things that happen in the world. That’s the journey I want to go on with the audience.”

And he is aware that people are not only watching his puppets, but that they are also watching him.

“I’m not a TV set, so I hear them out there in the dark, whispering,” he says. “I don’t know if an audience realizes that the person on stage can see them, too.”

Burkett believes the audience thinks he is more clever than he actually is. “They think my puppets are thinking and breathing,” he says, “but really the audience breathes for them.”

He recalls that after Street Of Blood a colleague remarked that, after so many years of work, Burkett seemed to be on top of his technique.

“You spend the first half of your life or career learning how to master playing the oboe or learning to dance or how to make this fucking thing walk across the stage,” he says. “And then you get to a certain point where you ask ‘What’s it all about?'”

For Burkett it is all about the process. The answers haven’t come in a flash.

“I wish there was one and I could say, ‘Hallelujah,'” Burkett says. “But about five years ago I started to realize there was something above the technique. I have developed a vocabulary which is all about breath and focus.”

Amongst all the rave reviews already garnered by Provenance, a writer from Edmonton noted that the show seems to be a transitional piece. “And I find that really funny, because it would imply that that writer knows where I’m going,” says Burkett. “But I don’t even know where I’m going. And what if I died next week? What if I decide I’ve got nothing more to say? End of career, write the book!”

Burkett doesn’t feel that he has wildly departed from his style. But he is definitely moving forward, clearing out old material.

“I had seven and a half hours of text in my head at all times and I needed to clear the hard drive,” he sighs. “And the only way I could think of doing that was to retire those old shows. It was time to move on.”

One of his new projects is Billy Twinkle, inspired by the people he has met over the years in the vast world of the puppet business.

“I’ve tried desperately to write a show without puppets, but it’s all about puppeteers,” he laughs. “So, there will be puppets in Billy Twinkle, but only as props.”

Billy Twinkle is an aging, bitter cruise ship puppeteer. “And there’s a southern evangelist ventriloquist,” he adds, “and the European performance artist with a toilet brush named Umlaut.”

Burkett swears that these people exist.

“When you grow up in the puppet world you do meet them all, and you meet all kinds. I’m not making this shit up,” he says. “I’m just stretching it a bit.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra