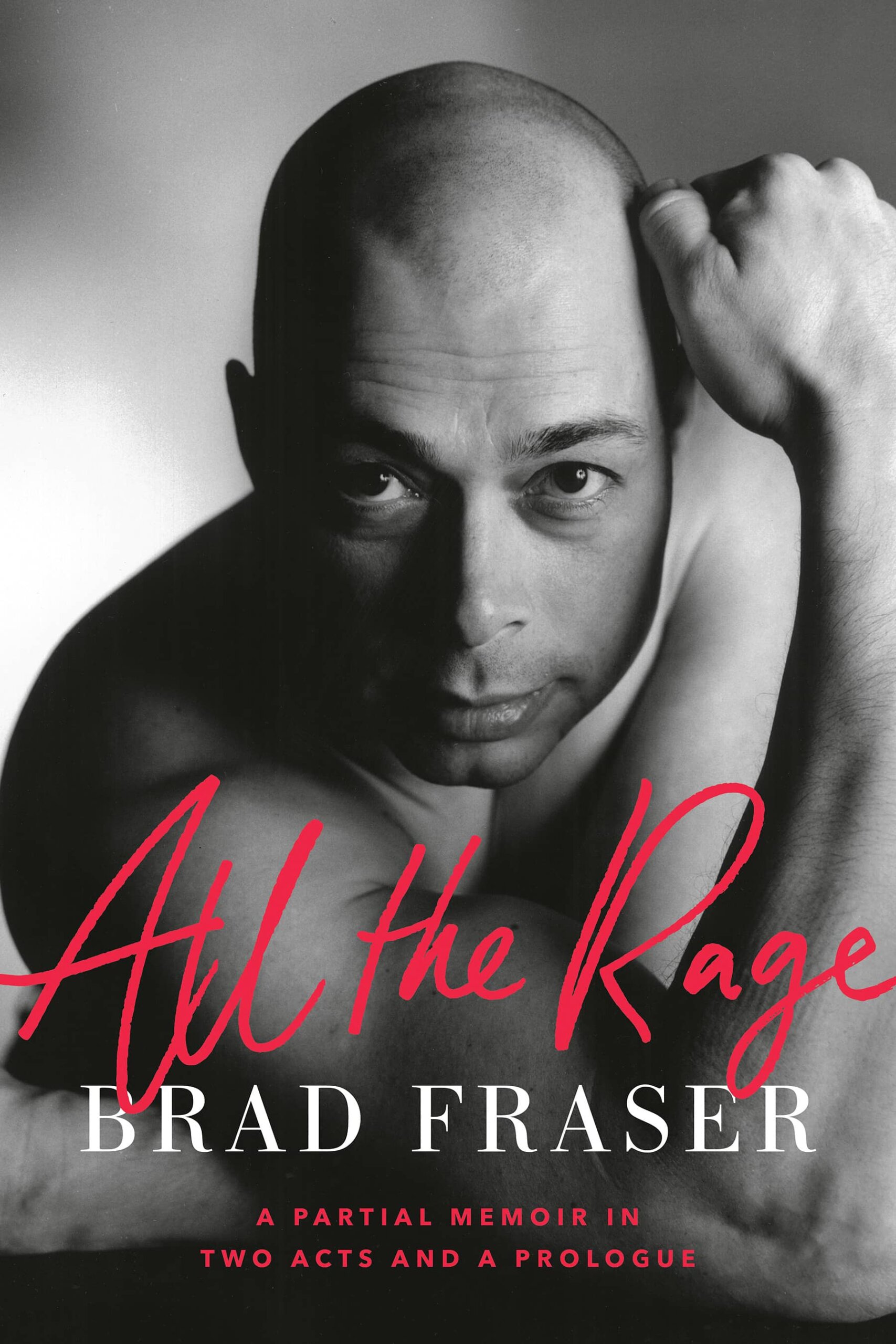

Brad Fraser had long resisted the idea of writing his memoirs. Despite a string of noteworthy theatrical hits over 30 years—including such landmarks as 1989’s Unidentified Human Remains and the True Nature of Love, 1994’s Poor Super Man and 2015’s Kill Me Now—the Toronto-based playwright and screenwriter didn’t see a line of connection.

But every year on World AIDS Day, Fraser would post photos of people he knew who had died of HIV/AIDS on social media. “I felt it was important for younger people to be reminded of all the people we had lost,” he recalls. It was on Facebook that literary agent and publisher Bruce Walsh saw the photos and Fraser’s accompanying texts; Walsh reached out.

“Bruce told me I should really tell my various stories of working in the theatre and the media through the lives of people I had lost,” Fraser says. “That had a lot more appeal. It became interesting to me because I wasn’t just writing about myself. If I could frame it through the AIDS crisis and the people I lost and the impact it had on me, that would be far more intriguing.”

The result is All the Rage, a book that begins with Fraser’s harrowing childhood in Edmonton, a life that began with physical and sexual abuse, and one that would change when teenaged Fraser would win a youth playwriting competition. The book takes us through lots of sex and drugs and multiple theatrical productions across Canada and around the world. There are intense highs—like when Fraser learned one of Canada’s most celebrated filmmakers, Denys Arcand, would adapt his most famous play Unidentified Human Remains for the big screen—and the harrowing lows of repeated losses of friends and lovers to AIDS. There’s a lot of pain in these pages, but there’s also a great deal of humour, like when Fraser describes having a sexual awakening while watching three men dressed up as rats on an Edmonton stage (their outfits were skin-tight and surprisingly sheer).

I spoke with Fraser from his home in Toronto’s Gay Village about his rocky childhood, the trauma of AIDS and his advice to young writers now.

What was the most emotionally difficult part of writing this book?

The childhood part was very difficult. When I did the first draft, I didn’t include the stuff about my childhood, I just started it with me going to high school and kind of obliquely referred to my family life and my father later on because I didn’t want to go there. I felt like I had dealt with that stuff some time ago and moved on. But then I chose to include it. So writing about that was damaging. I’m still healing from having to write that; it pulled the scab off a lot of old wounds. I haven’t talked to my family and found out who has read it and so forth, but it was very… you know, even when you have horrible parents, they’re still your parents and you have that feeling that you’re supposed to protect them. It was really hard. Writing about a couple of friends in particular who died of AIDS, that was very painful.

So you don’t know which family members have read this?

No, I don’t. But my mother sent me a note the day the book came out and said “I accept responsibility for what I did in your life and I know this was a very difficult thing to write, and I really appreciate it.” So that was helpful.

You deserve not one but a slew of medals for chutzpah for writing a racy play for the Walterdale Theatre when you were 21. People who don’t know the Edmonton theatre scene won’t know it, but that was one intensely blue-rinse theatre, run mainly by older people and catering to their tastes.

And it was the bestselling play of the season. It brought in a whole new audience. It was like the Flashback [an Edmonton gay club] was coming to the theatre. It sort of set the tenor for the rest of my career, because I was doing a variation on that for the rest of my career in various Canadian theatres. The show was Mutants and if you go to the Walterdale web site you can see photos of it there. It was really a trip to go back and look at that stuff. Having to go in and face the board of old white people was intense, and telling them I was going to sue them if they pulled the show, if they cancelled the contract. I couldn’t believe my nerve.

I love that you were the first person to get naked on the Walterdale stage.

Yes, during a production of [George F. Walker’s] Zastrozzi. And that was after they told me I couldn’t do it—I just took my underpants off before going on stage.

You’ve said that your queerness saved you.

Well, I come from a particular class of people: people who work road construction and do manual labour, and don’t have much education and often have a lifestyle that matches those things. And I didn’t want to lead that life. The theatre is a very classist construction. It really is there for the elites and people like them. For me to go in there and kick down the doors and say, “Fuck that. We’re going to tell some stories that are going to bring other people into the theatre.” That was a necessary thing for me to do, because I wanted people who come from where I come from to know that the theatre can work for them too. That’s always been my objective with what I’ve created: to bring people into the theatre who don’t normally go. That’s how [queerness] saved me. The trauma that I experienced and the unfairness, I think if I hadn’t been gay, I wouldn’t have found the way to do things differently. Gay kids were rejected if you were in [the working class]. For some who got rejected, it was actually a blessing in the long run.

“That’s always been my objective with what I’ve created: to bring people into the theatre who don’t normally go.”

But you have also said your queerness has held you back in the theatre.

In some ways. I wouldn’t say it’s my queerness so much, because we know lots of queer people in the theatre who have done very well. It’s my kind of queerness, which is confrontational, which didn’t apologize, which didn’t ask for anyone’s tolerance—it’s just an extension of who I am. I wasn’t writing plays like a lot of other people were. The gay plays in the ’80s, the characters were dying or were coming out to their parents or begging the world for tolerance. My plays were more fuck-you, this is who I am, this is how I function and these are our stories.

When AIDS hit the community, there was a sense there was nothing left to lose.

I was already like that before AIDS happened, and for the years that I thought I was positive—I figured I had to be, because everyone I had fucked was positive—that that was an incredible freedom. The stuff that I did with Remains, I don’t know that I would have done that if I hadn’t had the fear of HIV hanging over my head. I really felt like I had nothing left to lose.

You’ve changed some names in the book. Did you ask for anyone’s permission before the book came out?

In the first draft, I didn’t change anything. It was 150,000 words longer than it is now. I let a few people read it. The person I call Randy in the book said, “Look, I work in the Middle East, I work in Russia, I work in places where I can’t really be known to have gay friends.” So I changed his name for that reason. A lot of the people I’m writing about who I was intimate with are now dead, so I didn’t worry about changing their names. Some asked for their names to be changed. I respected that. At the same time, I didn’t want to have to ask people for permission to tell certain stories in my life.

I remember you came to Concordia University in Montreal once and spoke, and a young woman got up to the microphone and said, “Brad Fraser, you rock my fucking world!” I don’t recall anyone in the Canadian theatre inspiring that kind of response before—or since. You really were a rock star. One critic said you were the future of Canadian theatre. Others said, because you were bringing younger audiences in, that you were going to save the theatre. That must have been a lot of pressure.

I never felt that. I didn’t feel pressure in those years. I felt a sense of exuberance that, wow, I can finally do what I want to and say what I want to, for the few years it lasted. I never really felt like, “How can I live up to this?” I never doubted that I could, quite honestly. I didn’t doubt that I could do it.

I love the Canadiana of the book. You talk about doing theatre in Edmonton and Saskatoon and places that aren’t considered cultural centres. Theatre is supposed to be something that can happen anywhere, not just on Broadway or the West End.

I wanted to give a taste of that. I loved these cities across Canada. I’ve worked in these cities, I’ve had great times in them and horrible times in them. I wanted to give a flavour of them in the book. There was more about the cities in the original draft. I wanted to give a sense that in the theatre, your home is everywhere, and my childhood really prepared me for that because we were moving constantly.

You have been happy to remain in Canada, when so many gauge success by leaving for the U.S.

I could have made that leap, I could have had the green card. But I didn’t want to live in George Bush’s America. I didn’t even want to live in Obama’s America. There was a point where there was talk of me going to Manchester for a few years to do a residency, but I would have had to put my cats into quarantine for six months. So I chose to stay. My friends are here, my chosen family is here, but the work isn’t here. When Queer As Folk was done [Fraser was a writer and showrunner for the Showtime series for three years], I couldn’t even get arrested in Canada. Everything I was doing was in the U.K. or U.S. or some other part of the world. I haven’t had a production in Toronto in 12 years.

“I really believe that if Remains were written today, it would not get produced.”

You’ve railed against the Canadian theatre establishment, which you’ve said is safe and risk-averse.

And spineless. It’s only gotten worse. I really believe that if Remains were written today, it would not get produced. Not by the snowflakes who run the theatres now. They’re so afraid of offending anyone; they are so connected to government funding, and if anyone complains they’re afraid that will dry up. Right now, it seems our theatre is just aimed at other theatre people, and that’s the death of theatre.

What advice would you have for young creative writers today?

Probably the same advice I’ve given all along, which is don’t write for approval. Don’t let someone else water down your vision. Write to tell the truth. And if that’s not strong enough, then maybe this vocation isn’t for you. Because it takes a lot of courage, fortitude and strength to buck against the prevailing system and to try to do something different.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

All the Rage: A Partial Memoir in Two Acts and a Prologue by Brad Fraser is published by Doubleday Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra