Winning a short-story competition a decade ago changed John Patrick Gordon’s life. His story took top honours and the grand prize was a quarter ounce of pot.

“My story was about an average day in my life going to the Compassion Club,” he recalls. Back then, compassion clubs-which now legally grow and distribute marijuana to people with government-issued medical certificates-were still outlawed and all involved, from the grower to the distributor to the patient, were subject to arrest.

Gordon’s prize was waiting for him at the next marijuana rights rally: some primo BC bud. “They gave me a bunch of joints to smoke with my friends. It was the best pot I ever had.”

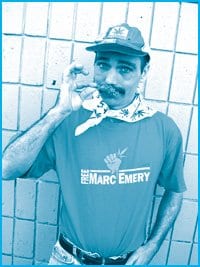

Now, “I guess I’m a full-time marijuana activist,” he chuckles.

“Being part of the pot-arazzi is really an exciting thing,” he continues. And he’s far from being the only gay man in the cannabis community, he notes. “I’ve found it welcoming to gay people.”

His history is one of seemingly insurmountable struggles, including sexual abuse by a priest as a young man. “I’ve had a difficult sexual history. When I left the seminary I had to expose the church for what was going on and deal with that. I realized I didn’t want to be another gay priest.”

Gordon went back to school and began volunteering with the Gay Games. But before the games could take place, he found himself in the Royal Columbian Hospital diagnosed HIV-positive and burned out by poor nutrition, lack of sleep and poverty.

Most of his friends disappeared. Gordon was hopeless. “I just wanted to lay down and die and get it over with. I was kind of wasting away. But I didn’t die and smoking pot is what got me out of the group home and the subsidized housing to live together with friends.

“Then I went into helping the mental health community, working with the West Coast Mental Health Network and serving on the board of the BC chapter of the International Association of Psych-Social Rehabilitation,” he continues.

Gordon soon co-founded the Unity Housing Society, a communal living space for 25 mental-health consumers living independently in five houses in the Downtown Eastside. Now he could finally smoke marijuana in the comfort of his own home, and in the years that followed he experienced a transformation. “I even found the strength to press criminal charges against the priest and civil charges against the church.”

Gordon feels he’s living proof of the benefits of marijuana use. “I’ve gone from taking antivirals to not, with marijuana. I’m a happy, more creative, active person.

“I don’t think that medicine has to be something that you take with a glass of water,” he says. “Medicine is something that can be enjoyed. I think that’s very important.”

His activism has meant coming out to his family on more than one level. “Because of prohibition, I had to hide my drug use and my sexuality from my mom. I knew she would have zero tolerance. When I said on the news, ‘I’m HIV-positive and I smoke marijuana for medicinal purposes,’ I didn’t even think about the HIV-positive part. My mom was freaking. I think it was easier for her to accept my sexuality than it was to accept marijuana-but now she’s come to accept both because she’s seen [the pot has] helped me physically overcome the HIV. You don’t know how many 40- and 50-year-old pot smokers are afraid to tell their parents, and that’s just bullshit.”

The laws have got to change, he concludes, and the gay community can help. “Marijuana and gay marriage bills were going to Parliament at the same time before the election,” he notes. “If we support each other we could get both bills passed and do a lot more.”

It takes many dedicated people to lead a political movement and Gordon’s writing is one way he contributes to moving cannabis culture forward. “Sometimes I think it would be nice to retire to the island and grow-but really? I enjoy the city and the pot culture here. I really feel that I’ve found my Tao.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra