'META-BIOPIC.' In fascination, Mike Hoolboom reframes the late Colin Campbell.

Daniel Barrow is one of the rising stars of the Canadian art world, a young man from Winnipeg who has been regaling audiences across North America with a miraculous form of quasi-cinematic storytelling that is both old-fashioned and innovative. Barrow’s delightful and wistful performances find him sitting behind an overhead projector, spinning wry, decadent, enchanting and often grotesque yarns while drawing on and manually animating acetate transparencies before a live audience.

Barrow’s protagonists are melancholic innocents searching for understanding. In The Face Of Everything (which Barrow brought to Images two years ago) a poor boy becomes consort to a Liberace double, even enduring plastic surgery to more closely resemble the rhinestoned and ruffled deity (as one Scott Thorson did in real life). Barrow taps into the intense, often hyperbolic feelings of tumultuous youth, leaving you not knowing whether to laugh or cry. Barrow’s writing, delivery, evocative drawings and endearingly lo-fi animation style contribute to a sense of longing and a nostalgic tone that is never arch or insincere.

While Barrow’s stories are not overtly autobiographical, he says he tries “to recreate specific images from the television and movie screens of [my] childhood.” He resurrects obsessions and touchstones from those lonely years spent in solitude with treasured objects and images. “Queer children, especially sissies, at least of my generation were taught to isolate themselves from other fruity kids. I personally couldn’t relate to the straight dynamics on the playground, so I spent most of my time watching TV. I think that’s how I developed such a strong relationship to story.

“My parents would beg me to go outside. But the outside world was fraught with complications and danger.” This inside world also meant collecting dollar store colouring books by unknown auteur Ken McDermid, Québécois CB radio business cards and documents discarded by a bitter preteen girl.

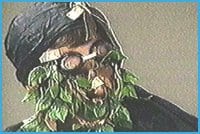

This profound interest in rejected ephemera finds new shape with Barrow’s jaw-droppingly entertaining project for this year’s Images Festival — an annotated compilation of the best and strangest examples of Winnipeg public access television entitled Winnipeg Babysitter. This beguiling selection rejoices in the creative wonders of free and democratic TV. “Public access television by its very nature, even when it’s camp or ridiculous, has a level of authenticity,” says Barrow. “Often the only incentive is exhibitionism and I can relate to that more readily than I can to the motives of commercial media and culture.”

The process was a labour of love. “I’ve spent the last two to three years searching for these tapes. The entire program was curated from childhood memories. The local public access archives were destroyed when larger cable companies bought the small ones and so the programs could only be found in the VHS collections of the original producers. When [they] didn’t save their own work, I had to rely on television collectors.”

The show will be presented on two adjacent screens, one with about 90 minutes of clips and the other with Barrow’s projected, scrolling text commentary. “I wanted to preserve the purity of the ’80s formalism — the various ’80s video toaster effects and text generators.”

The smorgasbord of pleasures includes: three contributions by the acclaimed Royal Art Lodge posse; a bevy of charmingly lumpen entertainers on the exceedingly egalitarian Pollock And Pollock Gossip Show; a Crimestoppers reenactment with a teenage rapist in a bad wig and music lifted from Hitchcock; two puppets named Desmond and Forgetful who sing about saying no to sniffing glue; a satirical take on post-nuclear cataclysm survivalists who adhere to the motto “The milksop whiner of today is the mutant of tomorrow,” starring filmmaker Guy Maddin; The Cosmopolitans, two old ladies on the organ and drums playing requests (turns out they were lesbian lovers!); two black balaclava and sawblade-decked dudes who perform a self-deprecating paean to the unholy awesomeness of heavy metal; the Silver Persian [Cat] Extravaganza; and more New-Wave interpretive dancing than you can shake a stick at.

Even though Barrow’s speech and drawings are absent, his voice is still clearly apparent in the affectionate, witty text commentary that fills us in on the secret history of the shows and their stars.

Barrow’s new collaged drawings and video sketch currently on view till Sat, Apr 29 at Jessica Bradley Art And Projects (1450 Dundas St W) make a nice introduction to his work, and they are accompanied by typically strong sculpture, prints and drawings by Shary Boyle and a fantastic new video by Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby in the group show Fantasia. Barrow’s drawings are related to an upcoming overhead projector performance titled Every Time I See Your Picture I Cry, and the manually animated video on display is a sort of rehearsal for the final show. The story concerns a garbage man who suffered through a childhood of constant eye infections, forcing him to wear a blindfold. The influence of comic books and the florid sentimentality of Victorian illustration are clear — both key gloom-grounds for the sad young man.

And while the narrative is fragmentary here, the bits are quintessential Barrow: “I’ve found the beauty in dullness,” reads the handwritten text carefully scrawled on Garbage Man. This suite of work is considerably darker in tone, provocatively juxtaposing murder scenes and ruminations on evil with Barrow’s characteristic damaged, fantasy-inhabiting fops, who occupy eerie and hazardous craft rooms and rubbish-strewn hopscotch courts.

In Toilet Brush, a man gazes at his impression in a commode’s reflecting pool while it is a garbage bin that returns his image in Path. Features are distorted and faults exaggerated, rendered with a rainbow of sickly-bright pencil-crayon colours.

The impermanence and decay of beauty is a prevalent theme in Barrow’s work. Many of his characters are reminiscent of earlier generations of gay men who shrouded themselves in glamour and a quixotic outlook to help sweeten the pathos and hardships of a wretchedly criminalized life. Perhaps the greatest influence on his sensibility is the dandy Quentin Crisp, who represents an ostentatious demimonde of homosexual aestheticism and camp, sophistication and wit that has sadly all but evaporated from the commercialized and mainstream gay world.

“I am drawn to people who romanticized faggoty personal style when everyone in their world tried to vilify it. I definitely have fantasies of being born in the early part of last century and lounging in Berlin cafés in the ’20s.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra