Up to this moment I have only seen this room in pictures and movies sent to me over the net. I have traveled all night to get here from Vancouver; first a so-called “Quick” shuttle to Sea-Tac airport and then the red-eye to Minneapolis.

The ring sits square in the center of the room. Through the haze of my sleeping pill, it glistens in the sunlight like some far off fantasy. I feel like I have found my Shangri-La.

Terry Klinger pushes open a sliding wooden door leading into an adjacent room. “This is the changing area and screening room,” he says. A video projection of one of his wrestling shows dances against the wall. The room is bigger than my apartment and has nicer furniture.

Terry has personally trained two wrestlers on the WWE’s current roster: Ken Kennedy and Shawn Divari. This is his ring and three days a week it’s home to Midwest Pro Wrestling’s School of Professional Wrestling. Today, it plays host to the World Wrestling Academy, which Terry hopes will be the first wrestling federation and school targeted specifically at queer men. This is what has lured me for the weekend from Vancouver to Minneapolis.

Terry was trained by “the strongest man in the world,” Ken Patera.

“I tell my students what Ken told me,” recalls Terry. “Half the guys in professional wrestling are gay or bi, so you better get used to it.”

By the end of the day we are joined by Dirk Henry from Tulsa, OK and Scott McKewan from Toronto. I haven’t seen Scott since Easter of 2004 at an event called the Passion of the Pro in Louisville, KY. It is Scott who convinced me to make this pilgrimage.

“You’re almost 40,” he wrote via instant message. “There are only so many matches left in you.”

It was my own mortality that prompted me to enroll in professional wrestling school to begin with. I had always felt like I missed my calling as a professional wrestler. My fear of pursuing it summed up every self-doubt that has ever plagued me.

“What will people think?” I agonized and still do.

But in January of 2003 I didn’t know enough people to care what others thought. I had the money, I had the time, and I wasn’t getting any younger, so I gave it a shot.

At 35 I was then the oldest person in the class and the only one with a bald spot. In the following eight months I would learn how to bump, body slam, and suplex.

As exhilarating as it is, wrestling hurts like hell. A few months into my training, I found myself in a hot tub with a friend who I hadn’t told about my aspirations for the squared circle. I was afraid he’d think I’d lost my mind.

“What happened to your back?” he demanded, as if he’d discovered evidence of child abuse.

Unbeknownst to me, I had a red and purple bruise the diameter of a basketball spanning my shoulder blades. I don’t know what shocked him more, the bruise or the explanation.

As well as learning to give the appearance of choking another man unconscious without inflicting any permanent damage, I wrestled in my mind to develop my own ring persona-my alter ego.

In wrestling there are jobbers and heels. The jobbers are the good guys who wrestle by the rules; the heels lie, cheat and deceive to gain the upper hand. And as in life, the heel usually wins.

Your typical wrestling match works like this: the jobber takes the upper hand early in the match and then loses ground because of a mistake or a dirty trick pulled by the heel. Then the jobber makes a series of small comebacks. The advantage shifts between heel and jobber until one scores the a coup de grâce, or “hot comeback.” Either the jobber prevails or falls victim the heel’s underhanded tactics.

Tainted victories are the stuff feuds are made of. Feuds lead to an endless string of rematches, each more shocking than the next. It’s this ongoing struggle between good and evil that draws frenzied crowds to ringside night after night.

“Don’t take this the wrong way but you should be the house flamer,” the federation’s requisite heavy guy told me one day. “You know, like Gorgeous George.”

I stopped wondering then whether or not I passed for straight.

Suicidal as it sounded, I actually considered the idea. Gay characters tend to generate a lot of “heat” from the fans and “go over.” But the thought of swishing through a packed arena at the Abbotsford Fairgrounds as the crowd chanted “fag!” made my skin crawl.

Even though the heavy guy was trying to be helpful, I did find it disconcerting that after eight months all anyone saw in me was a fag or a flamer; not a hero.

In the end it didn’t matter. The school and the federation folded-along with my dreams of working as a professional wrestler-before I ever climbed through the ropes for a paying audience.

Years later in Minneapolis, we have gathered to wrestle for the love of it rather than the glory.

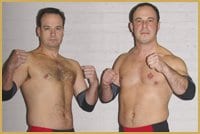

It didn’t take long to figure out who in our little group would play jobbers and who would play heels. Dirk and I look like Boy Scouts who kill time in wait at street corners for little old ladies who might need our help. Terry and Scott look like thugs who carry brass knuckles in their trunks, ready to deliver a cheap shot at the first opportunity. The stage is set for a storyline that will take the whole weekend to unfold.

There is just no point in professional wrestling unless you’re wearing the gear. Anybody can squeeze into a Speedo, but when you lace up those boots, your childhood dreams seem less like fantasy and more like reality.

“If you guys were real professional wrestlers you wouldn’t have two-thirds of this gear,” Terry says in disbelief. “I’ve never seen so much gear in all my life.” We won’t be together long enough to wear all the trunks and boots we’ve collected and lugged from our respective corners of the universe. It’s a kind of drag that is an important part of the erotic charge.

I slide through the bottom rope in boots, trunks, and a t-shirt; squat in the middle of the ring, and throw my back hard against the canvas, making sure to slap it with the palms of my hands.

“Land with the flats of your feet,” Terry shouts, always the trainer. He’s right. Needles shoot through the bones of my legs from where my heels slammed into the mat.

It takes a few tries to get it right before I start running the ropes. You’ve got to know how to throw your weight into ropes and turnbuckles without hurting yourself or breaking the illusion of the battle. If you can’t run the ropes there’s no point in learning anything else.

Before each match we pose for pictures in our gear. Considering how little we’re wearing, the photo shoots seem over-complicated.

“Suck in your gut,” Terry coaches from behind the photographer. “Now twist at the waist… A little more… Stop!”

From time to time he darts in front of the camera to move my foot half an inch one way or the other, then runs back out of the frame.

The resulting pictures look like they belong on posters for upcoming cards. But despite the aggressive poses, I see an innocence in them as there is in old beefcake photos from the ’50s or stained glass saints in church windows.

Terry and Scott defeat Dirk and I in singles competition in the build-up to a big tag team match. Dirk is a true tag team partner in and out of the ring. He’s there when I need him and always on my side. Before the tag match, he digs through his big plastic suitcase for just the right gear for me to wear. We settle on a pair of red and black trunks.

“Here,” Dirk says, handing me a pair of red laces. “It’s like a new pair of boots.” He’s right.

Dirk takes my wrists and starts wrapping them in red tape. Then he cuts some thin strips of black tape to make racing stripes on top of the red.

“Here, do me,” he says.

As I carefully wind the tape around his wrist I’m reminded of a famous jobber tag team who were rumored to be lovers outside the ring. I imagine them in the locker room before matches, lovingly taping each others’ wrists as Dirk and I do now.

One of them ended up committed to a sanitarium; the other went on to become a flamer and a heel in the WWF. It was the movie Ang Lee forgot to make.

Dirk wins the match for us because of infighting between Terry and Scott. Scott had been calling for Terry to make a tag, but Terry refused, opting instead to dish out more punishment. In the ensuing argument Terry turned his back on me, giving me time to tag in Dirk who pinned Terry from behind.

Thus the groundwork is laid for a big grudge match main event between Terry and Scott.

Watching the matches later on Scott’s laptop, I am impressed with how good they look. Whatever insecurities that ran through my mind in the ring are invisible on the screen. It makes me think I really did miss my true calling, all because I was afraid of being a labelled a jobber, or worse, a flamer.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra