First, a small confession: I have never read Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian tome Well of Loneliness.

Depending on your approach to literary appreciation, this is either a really big deal or no big deal. There are some who would wholly support me in my absence of reading. Like, hey, this is one book among many, right? Have I read every single piece of lesbian fiction and non-fiction out there? No. Should I?

Not if I don’t want to.

On the one hand a person could argue that classic works like Well of Loneliness likely had an impact on the genre of lesbian fiction as it developed, and as an appreciator of lesbian fiction I should want to have that foundational understanding that comes with reading founding text like this one. Especially, you know, if I plan to spend so much time writing about things like queer writing.

There are those who would say, “Holy crap, you call yourself a supporter of literary queers and you haven’t read the works of the acknowledged original literary queers?”

“Nice, Mariko. Nice.”

Typically when the subject of Hall’s novel and my not having read Hall’s novel comes up in conversation, and as a queer writer circling among queer writers and writing fans, it does, the assumption that follows is that I will eventually read Well of Loneliness. Presumably when I have time, like at a cottage or something.

The thing is, I don’t think I ever will. Not because I’m taking any kind of stand on the matter, the way I did with Titanic over a decade ago. I just can’t imagine I would like the book and so I don’t want to read it.

I don’t want to read it because, as most people have told me, and as the title clearly indicates, it’s a sad book, and I hate sad books. I especially hate sad books about lesbians.

When I first came out and started pouring over books about queers I was kind of shocked to find such a plethora of sad stories. Even the really beautiful stories were also really sad, like, say, almost everything Jeanette Winterson wrote, which I absorbed at a rapid, rabid pace when I first came out. The impact on my psyche, I’m sure, was not good. All this talk about how lesbians are always getting messed around, about how depressing being a lesbian can be. I drank a lot during my Winterson phase. I mean, okay, I was also living in Montreal where wine was always around the corner, but still. Sometime around my second year as an open and out homosexual I discarded any and all fictional works that had the chance of making me cry or feel like crying.

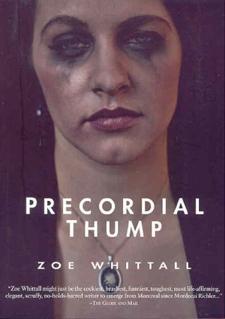

It was for this reason that Zoe Whittall’s latest release, Precordial Thump, sat for a long time on my desk, unopened. On the cover of this collection of poetry, published by Exile Editions, is a woman whose face is a blur of black-eyed tears. Sad, I thought. And even though I am and have always been a huge fan of Whittall’s work, I couldn’t bring myself to pick it up.

Although I can’t and won’t go into the spat of recent events, the details of conversations about supporting local art and artists, that lead me to read Precordial Thump, I will say that I’m exceptionally glad I did. This is not a sad book, in fact, it’s calculated, and prolific; it’s literary open-heart surgery.

In Precordial Thump, Whittall, among other tasks, completes a complex analysis of “the Liar,” both as a phenomenon and as an actual person that can and has stumbled into the lives of many. In this series of poems, which reads as carelessly genius, Whittall is part pop psychologist and personal historian, artfully combining found material with Polaroid memory captures.

Many of the poems contain a kind of “Dear John” frankness, as in the case of poems like “Dear Liary” and “Acceptance,” which also notes, calmly but not smugly, “Now, the liar must deal with/ the consequences of having loved/ a writer, compelled to describe/ both the shameful and sublime.” At other points in the book, most exceptionally in “Still Life with Ambulance Call Report,” Whittall crosshatches the life of a medic with the life of an artist, sensory overload and the meaning of a pulse taken two ways.

It’s a fricking relief, I have to tell you, to know that there are books out there that can talk about love and loss without leaving their readers in wells of loneliness. This is the kind of book that reminds you, when you read it, of what fiction can bring to a sad story: something other than sadness, insight.

Go and buy this book right now.

Oh yeah, and if you’d like to make your case for Hall, I’m always open to arguments. You can message me here. I’ll warn you that I’m kind of stubborn so it might not do any good. But you never know.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra