Eurovision is one of the most significant television events in the world. It might not feel that way to those in North America, but the annual singing competition, set this year for May 10 to 14, is among the world’s most-watched non-sporting events and the longest-running international music competition across the globe. Having also platformed folks who have since become some of music’s biggest stars—including ABBA, Olivia Newton-John and, of course, Canada’s own Céline Dion, who won Eurovision while representing Switzerland in 1988, two years before her debut English-language album—it’s a major cultural event that has become known for its camp appeal and over-the-top performances.

Far from the schlock and silliness that people outside Europe might associate with the competition, however, Eurovision is much more than a frivolous singing contest. Throughout its history, the show has proven to be a significant factor in geopolitics and a force among queer and trans communities around the world.

Credit: Robert Dear/AP Photo

I first became aware of Eurovision while living in Iceland in the summer of 2016. That year’s contest happened the week I arrived, and I remember walking the streets of Reykjavík, wondering where all the people were. I soon realized they were all inside bars, at parties or at home, watching the show. (Despite the fact that Iceland didn’t even qualify for that year’s Eurovision finals, it’s estimated that more than 50 percent of the country tuned into the contest.)

It wasn’t until a couple years later that I became fully invested. While couch-surfing my way through southern Europe in the spring of 2018, I spent a few days with a gay couple in Limassol, a city on the south coast of Cyprus. Again, the day I arrived coincided with the finals of that year’s Eurovision, and my hosts asked if I’d like to join them at a viewing party hosted by the national queer organization in the country’s capital, Nicosia, an hour’s drive north.

I happily joined them, and spent the night watching Eurovision in a courtyard inside Nicosia’s old walled city. Just a few steps away lay the Green Line, which separates the southern Republic of Cyprus from the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which have been frozen in conflict for nearly 50 years.

It was an energizing moment. Cyprus was expected to do well at that year’s contest (they ended up placing second), and my new friends were excitedly watching the performances and votes roll in. For my part, I had a flurry of questions: How does the voting work? Why is the person representing Cyprus from Albania? What’s the deal with the border just a couple streets over? Why is Australia in Eurovision? And this North Cyprus thing?

They listened patiently and tried to respond to my questions as best as they could. Some of the answers were straightforward. Most were somewhere in the range of “it’s complicated,” as they tried to explain the politics of the voting process and of their divided country. But I was hooked. From that moment forward, Eurovision has been forever linked in my mind to that experience in Nicosia—to the people, the music, the queerness and the politics.

This year has even seen the debut of America’s own Eurovision spin-off, the American Song Contest, which so far has received poor ratings and mixed reviews. And, on April 26, the official Eurovision Song Contest channels announced that Canada would be joining the actual Eurovision contest in 2023 with a preliminary competition called Eurovision Canada.

However, international reaction to Eurovision often focuses on the silliness of the competition and its over-the-top performances. The first line in the Canadian Press article about the contest’s expansion to Canada described it as an “oft-outlandish music spectacle,” for example.

And sure, Eurovision’s off-the-wall antics are part of its appeal. “It can be very camp,” says William Carter, a Texas-based Eurovision fan and commentator for ESCUnited, one of the many platforms that make up an extensive network of commentary and criticism about the contest. “There’s a little bit of subversiveness” that can be appealing, too, he adds. For example, Hatari’s 2019 performance, representing Iceland, in which the group, clad in BDSM attire, screamed at the audience in Icelandic while dancers around them acted out dark sexual fantasies.

But Carter says Eurovision can also be political. “Everything is politics,” he says. “It’s foolish to say that the geopolitical situation doesn’t affect what wins every single year.”

On the surface, the premise of Eurovision is simple. Countries select songs to compete against one another in televised live shows, with the winner selected based on a combination of a popular televote and a juried score. The show was introduced in 1956 by the European Broadcasting Union and inspired by the Sanremo Music Festival in Italy, which itself has been hosted annually since 1951.

The “origin myth” of Eurovision is that it began as a way of promoting “co-operation and European unity” following the Second World War, says Catherine Baker, a historian at the University of Hull. The truth is a bit thornier, however, and this unity myth has obscured some of the geopolitical divides that became entrenched in the contest later on. The actual reasons for starting the contest were about technological co-operation between international broadcasters and showing that it was possible to do something that Baker says “hadn’t been done before”: host a televised contest in one country and relay it live to other participating countries.

The contest was initially limited to a small handful of countries in western and central Europe. Over the years, it grew, welcoming some southern and northern European countries, but no country west of the Berlin Wall won the competition for more than two decades. The contest’s balance of power shifted slowly over time, but it wasn’t until the early 2000s when countries east of the Eurovision heartland began to be major players in the competition.

After the end of the Cold War, post-Soviet and other eastern European countries began to use the song contest to shape an independent national identity, explains Baker. When Estonia won in 2001, for example, they were the first in a series of winners that included other former Soviet republics, as well as countries such as Greece and Turkey, which had previously never won Eurovision. And, because the winner of the contest typically hosts Eurovision the following year, this meant the contest also began physically moving east.

According to Baker, these wins provided host nations with an opportunity to shape the way they were perceived by the rest of Europe and the world. In the case of the 2002 song contest, she says it was an opportunity for Estonia to show that it is a “modern, technologically advanced country,” bucking its stereotype as “post-Soviet” and aligning itself more with the Nordic countries. “Eurovision was the perfect kind of platform for that.”

“The contest developed a dedicated queer fanbase of folks drawn to its camp aesthetics, exaggerated performances, and messages of tolerance and acceptance.”

These examples only scratch the surface of the influence that Eurovision has had on the continent’s geopolitics. One of the most obvious examples of this contribution is how the competition has participated in the shift in the recognition of LGBTQ+ rights and politics in the decades since its beginning.

Eurovision’s queer history can be traced to the first years of the song contest. In 1961, Luxembourg’s representative Jean-Claude Pascal won with the song “Nous les amoureux” (“We the lovers”). The lyrics were ambiguous and refrained from using gendered pronouns, but told of a thwarted love affair. “They would like to separate us/ they would like to hinder us/ from being happy,” he sang. Pascal, who was himself gay, although not out at the time, later explained that the song was about challenges faced by LGBTQ+ people during an era when being queer and trans was still illegal in many countries participating in Eurovision.

Over the years, the contest developed a dedicated queer fanbase of folks drawn to its camp aesthetics, exaggerated performances, and messages of tolerance and acceptance. The contest’s first openly gay contestant, however, didn’t arrive until 1997, when Iceland sent singer Paul Oscar as their representative. Oscar performed a “dark sexual techno number,” which he sang while four women dressed in latex posed suggestively on a couch behind him, describes Elaine O’Neill, a Scotland-based fan and commentator for ESC Insight, another online platform dedicated to following the contest.

Credit: Sebastian Scheiner/AP PHoto

Another milestone was reached the following year when Israel’s entry, Dana International, became the first openly trans performer (and last, according to O’Neill) to compete. She ended up taking home the prize, and helped cement Eurovision’s place in queer culture.

“For me, a young trans girl at the time, extremely isolated in a country and culture that pretended trans people didn’t exist outside of a few late-night shock ‘sex change’ documentaries, it was a groundbreaking revelation,” O’Neill says about watching Dana International in the contest.

Since then, you’re bound to find an artist who is openly LGBTQ+ in any given year of the competition, along with a number of high-profile queer winners in recent years.

Perhaps most notably, bearded drag queen Conchita Wurst won for Austria in 2014 with her song “Rise Like a Phoenix,” which has now become a queer anthem. Her win was interpreted by many as a response to the anti-gay laws passed in Russia the previous year.

Despite these moments, O’Neill argues that it’s “easy to overstate” the presence of queer and trans artists and messages at Eurovision. While she acknowledges there have been major queer moments in the song contest’s history, she says this is often incidental to the songs or artists in the competition itself.

Officially, the song contest is meant to be apolitical, and as recently as 2014, hosts of the contest have been prohibited from wearing rainbow motifs, which the broadcasting union deemed “too political.”

“With a select few exceptions, Eurovision doesn’t tend to really push queer rights,” she explains. “It’s more of a space that fails to impede or punish them in any way.”

O’Neill adds that even the celebrated queer moments deserve some second thought. “People like to feel progressive, especially in a context removed from them,” she says. “You can vote for Dana International, celebrate transness, while knowing that it won’t affect your daily life at all.”

Credit: Corinne Cumming/EBU

The great irony remains that Eurovision is officially “apolitical.” Countries have been prevented in the past from sending entries that carry what the broadcasting union interprets to be political messages, and broadcasters have been fined when their country’s entry breaks these rules. For example, the Icelandic national broadcaster was fined after Hatari waved a Palestinian flag during the live broadcast of the 2019 song contest, which was hosted in Tel Aviv.

However, there have been numerous examples of political messages making their way through the cracks. There have been songs about the refugee crisis, the Euro crisis and this year’s entry from Serbia is a plea for universal healthcare.

“There have been numerous examples of political messages making their way through the cracks.”

“Even though people might dismiss Eurovision as silly and frivolous, it does create a platform for artists to have a really important voice, even though they’re not supposed to make political statements,” says Jess Carniel, a senior lecturer and cultural historian at the University of Southern Queensland in Australia. “You can’t actually extract culture from politics.”

In the case of her country, the contest has been an important way for Australian fans and artists to connect with international communities and articulate a specific cultural identity. In a somewhat bizarre anomaly, Australia has been participating in Eurovision since 2015, after years of enthusiasm for the competition, which Carniel attributes to the presence of the show on Australian television since the 1980s.

“There is this stereotype of Australians as being white and blond and blue-eyed and surfers,” Carniel explains. Australia has used the competition to send representatives who resist this stereotype, including performers who have roots in Malaysian, Filipino, Korean and Aboriginal communities in the country.

For other countries, Eurovision has been an opportunity to articulate more serious political objectives. In particular, Ukraine’s participation in Eurovision has been intimately connected to the political climate and events within that country. In 2004, only a year after its first participation in Eurovision, Ukraine took home the top prize for the first time with the song “Wild Dances” by singer Ruslana. Baker says that song drew inspiration from the music and style of the Hutsul ethnic group who inhabit the Carpathians near Ukraine’s border with Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania. During her energetic performance, Ruslana sang and danced in a sexy Xena the Warrior Princess-inspired outfit, surrounded by other dancers who powerfully pounded their feet on the stage.

“It was an opportunity to really make the case for Ukraine as a nation that was looking toward Europe rather than looking toward Russia,” says Baker.

In the year following Ruslana’s win, the Orange Revolution broke out in Ukraine over disputed results of a presidential election which had claimed a pro-Russia candidate as the winner. During the 2005 contest hosted in Kyiv, the revolution and its political aims took centre stage. Ruslana had herself been a major supporter of the protests, and that year’s entry for Ukraine was a rap band that had become unofficial representatives of the cause.

Kyiv capitalized on the international attention it received while it hosted the contest, and tried to position itself as a place that was open to the West. Ukraine abolished visas for EU visitors for the first time for the competition, and never brought them back.

“Eurovision got more of a footprint in the city space of Kyiv than any other host city had given it,” she explains. “That’s continued ever since. It’s not just something that happens in a theatre or an arena on a Saturday night anymore.”

In 2007, Ukraine again garnered attention when it sent drag performer Verka Serduchka to the competition in Helsinki with the song “Dancing Lasha Tumbai,” which finished in second place. Aside from the attention for the performance’s unabashed embrace of kitsch—she performed the frenetic number in an outfit that resembled part alien and part disco ball, accompanied by five silver- and gold-clad backup singers and dancers—many also read a political meaning into the song’s lyrics. Fans and critics interpreted “lasha tumbai”—words made up by Verka Serduchka herself—to mean “Russia goodbye,” in reference to the escalation of Russian involvement in Ukraine since the Orange Revolution just a few years earlier.

Following Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine was unable to compete in the 2015 song contest due to financial and political reasons. However, the country returned to win the competition in 2016 with the song “1944” by singer Jamala, whose lyrics told of her family’s own experience with the Soviet Union’s deportation of Crimean Tatars. It was easy to see the historical parallels that were being drawn.

As we near this year’s song contest, which will broadcast in the second week of May, this iteration is no exception to the way that geopolitics inform and shape the contest. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, the European Broadcasting Union banned Russia from the contest, and the Ukrainian entry has become a fan favourite.

“The huge public support for Ukraine across Europe means that Ukrainian band Kalush Orchestra might simply have the winning narrative without needing to even sing.”

“Eurovision fans have become invested in the idea of Ukraine because they’ve connected to Ukrainian culture through what they’ve sent to Eurovision,” Carniel explains about the country’s popularity.

There’s a parallel between this year’s competition and the contest in 1993, when Bosnia and Herzegovina entered Eurovision for the first time following the breakup of Yugoslavia. The Bosnian War had been ongoing for more than a year, and the country’s entry had to escape the besieged capital of Sarajevo under sniper fire to make it to the contest in Ireland. Although the entry wasn’t well-received by juries, which at the time were the sole deciders of the contest’s winner, there was enormous public support for the Bosnian and Herzegovinian entry.

Nearly three decades later, this is a scenario we might see play out again on the Eurovision stage. The difference this year is that, going into this year’s competition, Ukraine is expected to be one of the top contenders to win.

“Rarely have we had a country who might win simply for showing up,” says O’Neill. “The huge public support for Ukraine across Europe means that Ukrainian band Kalush Orchestra might simply have the winning narrative without needing to even sing.”

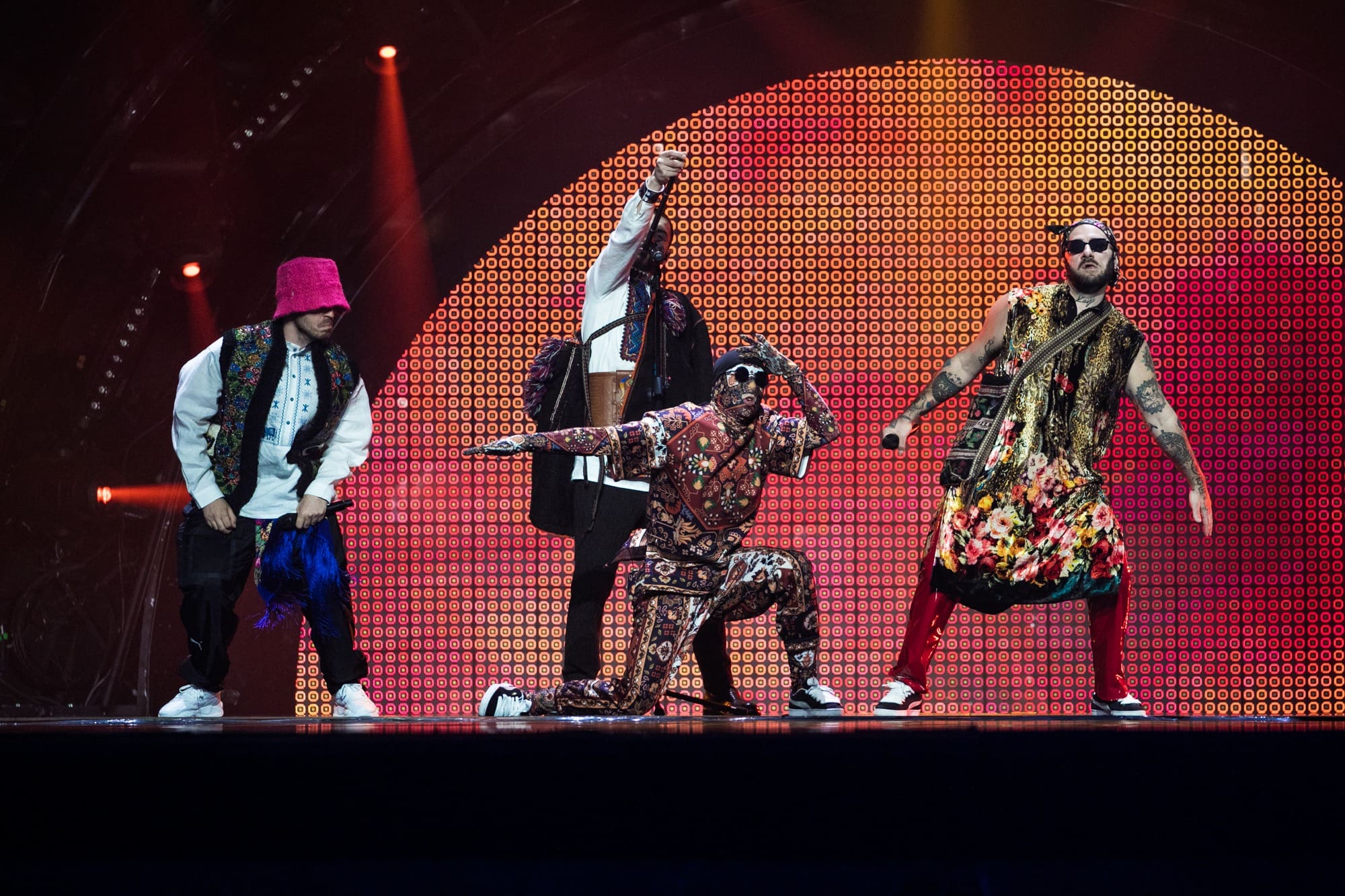

Beyond the support they will get for simply “showing up,” Kalush Orchestra is also an example of Eurovision at its best and most interesting. The group’s entry, “Stefania,” is a mashup of Ukrainian folk and hip-hop, with lyrics about the lead singer’s mother and a solo on Ukrainian flute—called a sopilka—midway through the song.

The rest of this year’s entries round out a lineup that is typically Eurovision. They range from heartfelt ballads such as the United Kingdom’s “Space Man” by Sam Ryder, to Norway’s bizarre-yet-catchy “Give That Wolf a Banana” by Subwoolfer, to Moldova’s folk-punk act Zdob și Zdub & Advahov Brothers with their song “Trenulețul,” which O’Neill says “wouldn’t sound out of place at a Romanian wedding.”

For my part, I plan on hosting my own Eurovision party for the first time since moving to Berlin. I look forward to introducing the contest to friends who have never watched it before and experiencing its joyful queerness, complex politics and camp excellence. With any luck, they’ll feel the same way I did the first time I saw Eurovision—a little confused, a lot excited and, at the risk of sounding overly earnest, moved by the music.

This story was published with support from Critical Minded.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra