Two Iranian boys, aged only 18 years, hanged by the neck. The photos were horrific for any who saw them, but the LGBT community was further shocked when it was claimed that Mahmoud Agari and Ayaz Marhoni’s only crime was being gay.

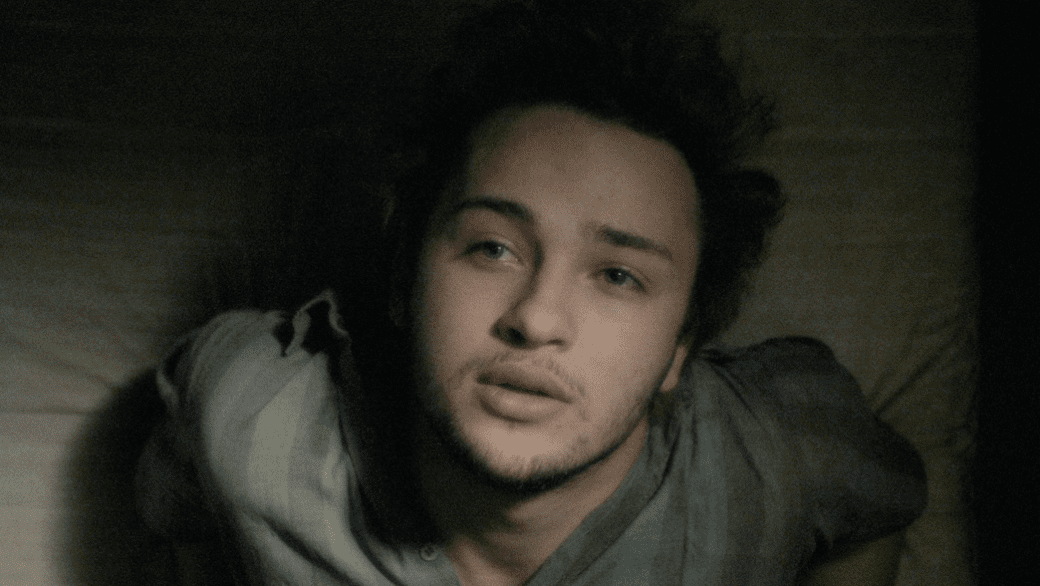

Filmmaker Darwin Serink was deeply affected by the media coverage of Agari and Marhoni’s 2005 executions. Nearly a decade later he has channeled his lingering grief and outrage into a beautifully haunting short film called Aban + Khorshid. Daily Xtra caught up with Serink to discuss his inspiration for the project.

Daily Xtra: Many of us remember the first time we saw the photos of Mahmoud and Ayaz’s deaths, and the emotions stirred up by the premise that they had been killed for loving each other. What pushed you to create a fictionalized backstory for the events?

Serink: I had first observed those very shocking still images back in 2005 while I was still in college. The executions had just happened, and they resonated with me in a profound way. I sat with those images for years, questioning the extremism of what’s portrayed in those photos, and always wanting to do something with that image. After five or six years I came to the conclusion that a short film about two fictional characters experiencing what those two young men must have experienced was a way to express to the world a story that needs to be told.

After Human Rights Watch and the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission expressed the opinion that the executions were not solely due to the boys’ sexuality, the story seemed to just go away. But it did seem to be a watershed moment for discussing the plight of gay men living in areas that practice sharia law. What is the larger story here?

A lot of the details have been kept silent, and there’s been quite a bit of controversy about the story of these two young men. At the end of the day what I was interested in was conveying a narrative about humanity and what we do in the name of fundamentalism. I wanted to use these two characters to express the power that love has to carry one through the most oppressive and extreme circumstances.

The dialogue of the film is entirely in Persian, with English subtitles. Was it difficult to craft a story in an unfamiliar language?

I wrote the original script in English, then Arsham Parsi from the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees translated it into Persian. To create a film from the perspective of an English speaking Canadian American and not have it in its native tongue would, I think, be not cool. The whole project was to honour the culture, to honour the people and the two characters.

Given ISIS/ISIL/DAESH’s latest hobby of executing gay men by throwing them off buildings, do you think that Aban and Khorshid’s story has a particular relevance today?

Aban + Khorshid is more relevant today than ever before. Fundamentalism is fundamentalism. Be it ISIS, the Iranian government, as long as there are institutions that propagate extremist ideologies and execute their own citizens based off fear and hate, there will be a need for films, music, poetry and art the likes of Aban + Khorshid.

The realities of gay men living in these regions seem very far away from the relative security we enjoy here in Canada. Aban and Khorshid surely represent many who have loved and died simply for being homosexual. How does this reality inform your life as an LGBT Canadian?

There’s a lot going on with America right now with LGBT equality and marriage, but when you step outside the American bubble things are a lot different globally. You can complain about your life. We all can. But things are 180 degrees different from here around the world. So it’s really about taking inventory and realizing what we have. I live in Los Angeles now, but I was born in Canada. How unbelievably lucky is that? It’s like I won the lottery.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra