I think I might be in love with the boy with the virgin eyes.

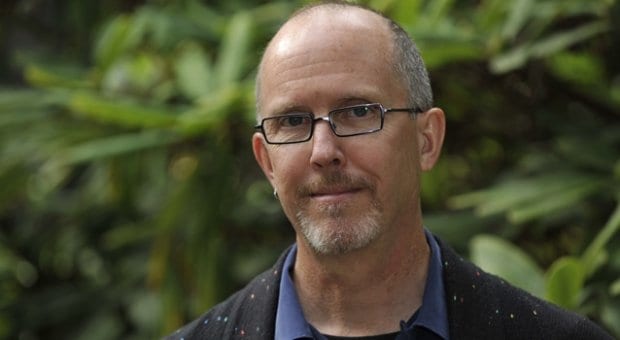

At least I’m in love with the sad, erotic and desperate real-life encounter that inspired Canadian poet John Barton’s poem “For the Boy with the Eyes of the Virgin,” also the name of a book of selected poems from his nine collections, written over 30 years.

If the collection were a greatest hits album, the genre would be jazz, Barton says, “because it’s a lot of improvisation, and when I begin a poem I don’t necessarily know where it’s headed.”

“For the Boy with the Eyes of the Virgin” left me with the loneliness I usually feel only after finishing a novel that has characters who have become my friends, and who, when the book is finished, I hate to let go. It is a testament to Barton’s vivid lyricism that after reading a poem that spanned only three pages, I felt that same affinity for his characters.

“I was in San Antonio, Texas, about 20 years ago,” he recalls. “I had spent the day visiting the Spanish missions. It was very hot, and I was almost sunstroke, and I went to get something cold to drink, and this young kid just came up to me and said the first line [of the poem]: “Let me be your ice.”

Let me be your ice,

the boy says in the Texas heat,

black mestizo eyes,

broad face, bare chested, barely sixteen

The poem is one of many inspired by the AIDS epidemic, which Barton has been chronicling in his work since the 1980s. It could be said that these poems are his most important because of how they have captured the evolution of a disease that continues to shape the gay community into the 21st century.

When I wonder aloud if some of his poems on HIV/AIDS are still relevant today, he assures me that “it’s still relevant, since people are catching it every day.” And he isn’t concerned with his work becoming antique, even embracing the idea. “In a sense, I wouldn’t mind if my poems became historic rather than current,” he says, “because that would mean it’s behind us.”

With the recent ignorance spewed by a certain hotel heiress who thinks gays on Grindr are “disgusting” and are all, like, totally “going to die of AIDS,” it’s painfully obvious that the stigmatization is far from behind us.

“It saddens me,” Barton confesses. “I think there are two kinds of reactions you get from the mainstream community: one is that kind of homophobic commentary, and then there are the people who think that there is no discrimination against gay people because all the legal pretensions are in place, so there’s this kind of complacency. They think that the struggle for equality has been won, but then you encounter people saying things like what Paris Hilton did, and you realize that that tolerance that we think is going to spread in the mainstream world is actually very shallow.”

That small-mindedness in society is also reflected in the publishing industry, with Barton questioning whether some of his work is rejected because of its gay content.

“I think it’s still problematic sometimes,” he admits. “Often critics are talking about universality and saying, ‘Does this have universal themes?’ And I think too often with gay writing people look at it and think it’s not universal. But when you look at it, at gay men writing love poems to one another, what’s the difference? It’s love, and isn’t love a universal emotion? Whether it’s articulated in gay terms or straight terms, both types of love are on equal footing.”

There’s no denying that the publishing industry is a lot gayer than when Barton’s career began. While editing an anthology of gay male Canadian poetry, he “noticed that 1990 seems to be a really important year. Nearly half the anthology is composed of poets, or poetry that was published after 1990.”

Through his poetry Barton carries forward memories and, by doing so, helps carry forward gay culture. His poems are an education on beauty and the elimination of fear.

“I always think the measure of how much society will change will be when there are no teen suicides,” he says. “That no child grows up and realizes he’s gay and feels like an outsider, or feels shunned, or feels brutalized. When that changes, I think our society will have fully embraced tolerance.”

To help that happen, the poet has a plan. “It’s almost like I’m setting a trap,” he explains, “and if I can reel someone in with a well-turned line, and when they come to the end he or she feels something new, and are maybe encountering something they’d not ever considered, then I feel I’ve succeeded.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra