“Magic is about putting desire into the world,” Jamie, the witch protagonist of Lessons in Magic and Disaster, tells her non-witch partner after many magical mishaps and interpersonal misunderstandings. She goes on to reflect that even though magic is about becoming acquainted with one’s own desires, it’s all too easy to lose oneself in the process of casting spells. This uneasy balance between self-knowledge and loss of self is at the centre of Charlie Jane Anders’s most recent novel. Jamie, a twenty-something PhD student of 18th-century literature, has already lost one of her mothers to illness several years ago. Now, she’s worried about her other mother, Serena, who has shut herself away after the loss of her partner and the destruction of her career by right-wing pundits. Jamie decides to share her magical abilities with her parent in hopes of bringing her back to the land of the living—but Serena, headstrong and grieving, is an unpredictable force, and soon their joint magic goes terribly awry. Written in straightforward, accessible prose, and dedicated to demonstrating healthy communication in intimate relationships, Lessons in Magic and Disaster is a fairly gentle read, despite some of its more painful subject matter. It’s a perfect summer book for people who like their magic with a good dose of emotional processing—and 18th-century queer history.

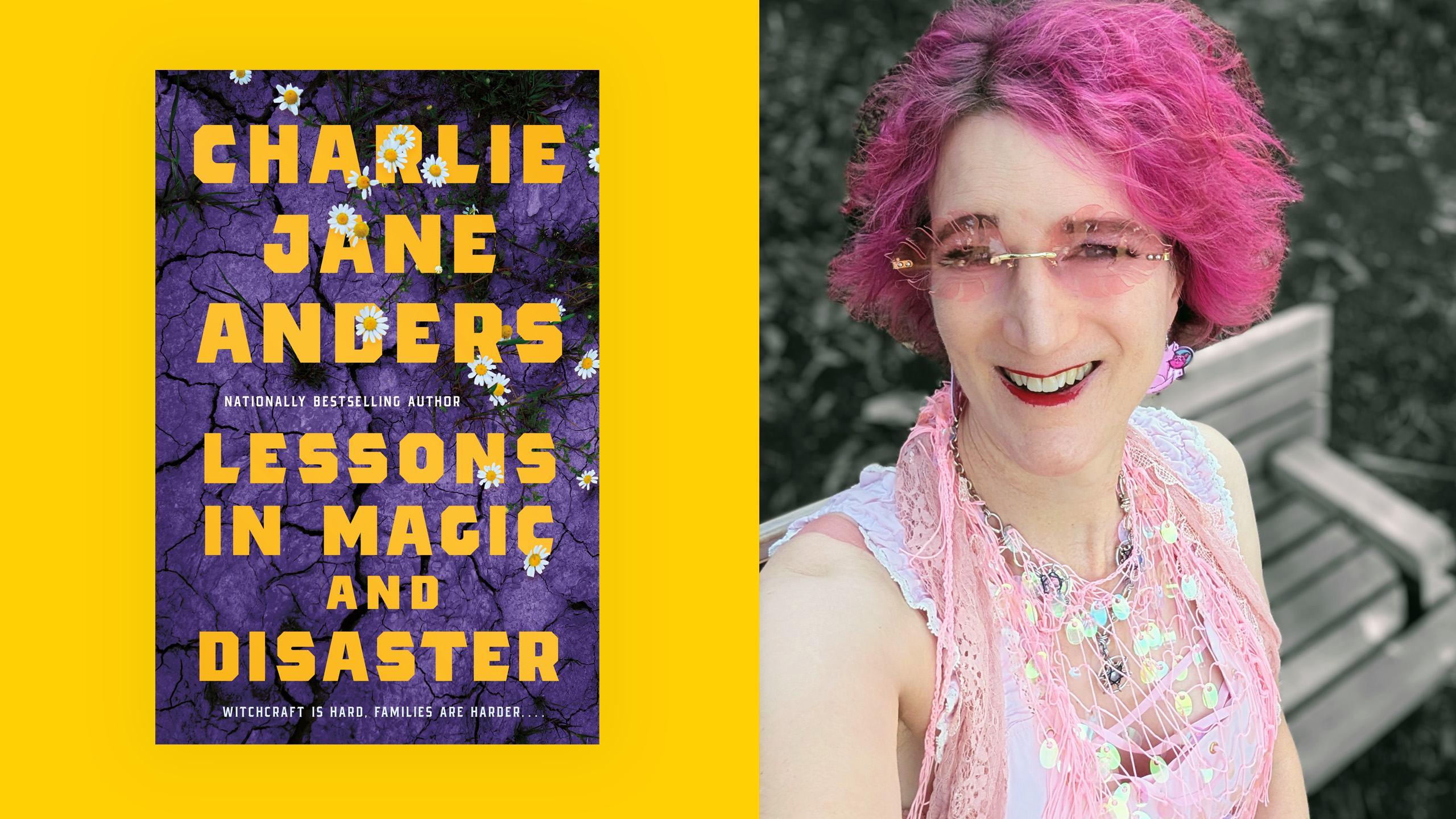

Anders is the author of the novels All the Birds in the Sky and The City in the Middle of the Night, and has won the Hugo, Nebula and Lambda Literary awards for her writing. She also co-created the trans mutant hero Escapade for Marvel Comics. Given its title, and the sci-fi and fantasy focus of the Hugo and Nebula awards, you might expect Lessons in Magic and Disaster to be set in a fantastical world full of wizardry. However, it is much more of a campus novel and a queer historical novel. Jamie does not study at some magical school for witches—she attends a regular college, and is writing her dissertation on the provenance of a mysterious novel from the 18th century. Rugby College, though fictional, is a true-to-life small college in the northeastern United States, plagued by funding cuts and rising right-wing pressures to censor leftists, especially trans students and lecturers, and Jamie is both. The troubles in Jamie’s world are mainly familiar, rather than otherworldly—grief, loss, a difficult parental relationship, the stressors of academia and its increasingly limited job market, and sudden bouts of dysphoria brought on by the trolling of conservative students and online pundits. Rather than being grandiose, Jamie’s magic is subtle, practised in secret via careful rituals, and learned through her own intuition.

Jamie’s magical method, discovered when she was a lonely, closeted trans child, involves finding a secluded, abandoned place, somewhere that humans have used and then left, where she then intuitively combines several objects that are meaningful to her, along with an intention and a desire for something particular to change—for the better. She casts spells to help her with her dissertation research, or to direct financial abundance to a peer’s medical fundraiser. Jamie is careful not to cast negative spells, or to ask for anything too big, sensing that the balance of the world is delicate. However, when she gets Serena involved, her mother has no such qualms. Driven by grief and guilt, rather than her own true desires, Serena’s spells have increasingly bad consequences: a house filled with foul odours, disappearing loved ones, an enemy gaining rather than losing power. Jamie, ever the academic nerd, suspects that the key to restoring balance in her family and fixing her mother’s magical misdeeds might lie in an unexpected place: Emily: A Tale of Paragons and Deliverance, a fictional unattributed novel from 1749 and the subject of Jamie’s dissertation.

One of the pleasures of Lessons in Magic and Disaster is its intertextuality. Jamie is dedicated to “the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake,” a pastime which she feels increasingly distanced from thanks to the demands of her poorly paid teaching work, rising rents, students’ increased reliance on AI and the other pressures and constraints of late-stage capitalism. Jamie loves her actual research, despite all the stressors surrounding it. Her worries disappear when she’s engrossed in the archives: “Obsessing about the meaning of a juicy text is dang medicinal.” Her research proves to be one of the more compelling elements of the novel. Emily, Jamie theorizes, is a woman writer’s response to novels written by men of the same era, like the real-life author Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa and Pamela, in which women who try to live in accordance with the era’s rules of good behaviour end up suffering at the hands of men who do not adhere to those same rules. While Richardson’s novels depict women’s suffering, Jamie notes, they do not question the system that created that suffering. In contrast, Emily is about “a young woman who plays by the rules and still controls her own life.” Emily becomes the moral instructor of a younger man who has fallen in love with her, rather than her being controlled by him.

Thanks to some magic rituals, Jamie comes across key documents that prove that Jane Collier, a real-life figure and contemporary of Samuel Richardson, was Emily’s author. Jamie later discovers letters written between Collier and Sarah Fielding, the overlooked novelist sister of Henry Fielding (Tom Jones). Collier and Sarah were lifelong friends, if not more. The letters provide a key to a fairy tale found within Emily’s main narrative, involving a princess (representing Sarah) who risks losing her reputation when seen in the company of a charming “strolling player,” who represents Charlotte Charke, aka Charles Brown, a real-life actor. Charke/Brown played male roles in the London theatre and lived as a man in much of their everyday life. Jamie finds out that Collier was able to stop the vicious rumour mill from ruining Sarah’s reputation—but how? She races to uncover this mystery, as her own mother unravels, casting spells that could have dire consequences on both their lives.

Anders cleverly mixes historical figures and texts with her own inventions: she uses real details from the lives of Sarah Fielding, Jane Collier and Charlotte Charke/Charles Brown, while inventing others. Both Collier and Fielding are now recognized as early feminist writers who wrote satirical works about patriarchal society; they really were friends, and even wrote a novel together, 1754’s The Cry. However, Anders invents their epistolary exchanges for the book, since their actual letters did not survive. She concocts the central text, Emily, which she provides convincing samples of throughout the main text. She also invents the scandal involving Fielding and Charke/Brown. What emerges from all this intertextuality, real and invented, is a common theme: men who seek to ruin the reputations and lives of independent women in order to gain and maintain power over them. While Sarah Fielding’s reputation was under threat due to her relationship with Charke/Brown, Jamie’s mother’s housing-rights-focused legal career was once ruined by a right-wing smear campaign, and Jamie’s own teaching career is now at risk due to anti-trans and misogynistic trolling by conservative students and online personalities. There is not, Anders points out, much difference between the patriarchal structures and methods of control of the 18th century and those of the 21st.

Lessons in Magic and Disaster, in addition to being a deeply feminist text, is also squarely anti-capitalist. Jamie suspects that “capitalism is a huge part of the reason why magic is so difficult: nobody knows what they want, because we’ve all been brainwashed to want garbage.” Much of her time outside the college library is spent trying to help her mother rediscover what she wants in life. Though Jamie is often frustrated at having to parent her own parent, she also recalls the supportive household she was raised in. Both Serena and Mae did their best to raise Jamie with love and openness: “You cannot mess up so badly that you will not be loved,” she is told as a child. Both mothers are immediately accepting of Jamie when she comes out as trans as a teenager. Anders draws a link between Jamie’s research and Jamie’s own life: Jamie loves both Fielding’s and Collier’s writing because they examine the tensions between “tyranny versus mutual aid,” tensions that she herself navigates, between the transmisogyny of those in power and the imperfect but unshakable support and love of her family, and her partner, Ro. She is drawn to these women’s works, which “expound a philosophy of kindness and cooperation, putting aside vanity and greed,” placing them in opposition to capitalist frameworks even if they were not explicitly anti-capitalist.

The novel sometimes suffers from stilted dialogue, and from Anders’s tendency to spell things out rather than let the reader form their own understanding of the interpersonal dynamics between her characters. Overall, though, it’s a well-crafted, thoughtful novel of magic, queer subterfuge, self-discovery, 18th-century feminist and queer history and family healing. It’s refreshing to read about the well-researched, partly imagined inner lives of Sarah Fielding and Jane Collier; far from being stuffy and irrelevant, the lives of 18th-century women are shown to be complex, intriguing and possibly gay. As Jamie retorts to one of her conservative students, who complains that her class on the English novel is obsessed with freaks and perverts: “Freaks and perverts created all the culture worth talking about.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra