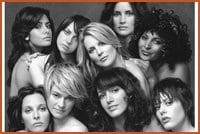

The L Word captures more diversity than it gets credit for, Ilene Chaiken tells me, as her crew gets ready to shoot the final episode of season two in Vancouver last winter.

Chaiken is the mastermind behind the groundbreaking drama that sent a shiver through lesbians worldwide after it premiered on Showtime last year.

Most of the buzz was positive – beyond positive, in fact. It was downright drooling. The show is, after all, the first-ever, made by lesbians for lesbians, prime-time serial ever to hit the airwaves in North America.

And then there’s me.

Sure, I like the show well enough, but I rarely, if ever, see myself reflected in its characters, storylines, sets or costumes.

Of course, that wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, or even a shortcoming on the show’s part, if I had more shows to choose from. But I don’t. This is it. This is all we’ve got. And I, for one, am less than impressed.

“I’m just trying to tell stories of lesbian lives,” Chaiken tells me.

Well, if these are stories of lesbian lives, maybe I’m not the dyke I thought I was.

Chaiken’s lesbians are all impeccably coiffed (and note: they have way more hair to coif than I do), LA-glamorous, fancy car-driving, latte-sipping, power suit-styling, upwardly mobile 30-somethings. Glamorous is the key word. It pervades everything they do, everything they are. They are nothing if not LA. And there isn’t a butch dyke in sight.

What’s the deal? I ask Chaiken. Why did you choose to portray lesbians this way?

“I’m starting out by telling my stories,” the longtime LA resident explains. “It’s not autobiographical but it reflects my world.

“I’m trying to tell stories as I’ve lived my life. Things I’ve seen in communities around me that I know have been unrepresented in pop culture. I’m telling those stories as best I can.

“It may be slightly glamorized,” she concedes, but “this is television and as filmmakers and storytellers we have the prerogative of making our stories a little more glamorous than they might be in real life.”

But The L Word’s characters are “not a wild exaggeration,” she insists. “These people are pretty real to me.”

Really?

Okay, I’d be the first to admit that Dana (Erin Daniels), the pro tennis player just venturing out of the closet, blossomed into a realistic character and even grew on me as season one progressed. And yes, I do occasionally catch a glimmer of lesbian truth beneath the power suits of the successful yet conflicted Bette (Jennifer Beals).

But the others? Take Shane (Katherine Moennig), for example. Shane is supposed to be the resident glam-butch heartthrob, but all I see is a cardboard cut-out. Her one-dimensional portrayal of what she thinks a lesbian might be (tough yet charming in a stylishly messy sort of way) is only occasionally punctuated by what seems to be a stilted imitation of Vancouver author Ivan E Coyote’s patented butch moves.

That doesn’t say real lesbian to me. I’m not sure what it says, but it doesn’t evoke the uniqueness of lesbian culture, identity and expression.

I mean, where are all the unstylish, multifaceted, middle-income, co-op-dwelling, herbal tea-drinking dykes living outside the dominant culture?

I’m serious.

Where are all the people forging their own, distinctly lesbian, ways of being? Where are all the real butches? Where are all the leather dykes? Hell, where are all my hockey buddies?

And why do Chaiken’s lesbians all seem so mainstream?

“Radicalism comes in many forms,” Chaiken reminds me – though she soon concedes that most of her characters are firmly rooted in mainstream culture and aspirations.

Subcultures aren’t central to her storytelling, she says, because they mostly fall outside her everyday world. “We might visit them from time to time, but it’s not where we live.

“I think most lesbians live more conventional lives,” she continues. Which is to say they live “in a way that most people are comfortable dealing with.”

In fact, she says, “most lesbians are probably so very much like straight people with the exception of sexual orientation.”

Excuse me? I may be an upwardly mobile 30-year-old, but I am a dyke first. It’s not something I just visit from time to time. It’s who I am and pervades everything I do. It shapes the way I think, the way I act, the expressions I craft, the way I build my home and my family, the way I see the world around me and the way I interact with it.

And I wouldn’t want it any other way.

As former Kinesis editor Nancy Pollack once said to me, while lamenting the easily digestible, assimilationist, pop culture face of lesbianism today:

“There’s not a butch in sight. There’s not a rebel in sight. And if lesbianism is not about rebelliousness, I don’t want to be part of it!”

Amen to that.

Of course, Pollack and I may be out-voted (not to mention lynched) for our lament.

The L Word has a very devoted dyke following – people who not only see themselves reflected in the show, but relish its every scene. People who say they’re sick of the one-note-butch portrayals that dominated most mainstream lesbian imagery prior to The L Word. People eager to add a little glamour to the picture.

“Since the dawn of gay liberation, lesbians have been relegated to the role of the queer community’s fishwife,” writes Kera Bolonik in New York Magazine. “Just turn on the television and you’ll see us decked out in fanny packs, tool belts, Birkenstocks, ear cuffs and bolo ties, as we revel in man-hating, tofu-eating, mullet-headed, folk music-loving, sexless homebody glory.”

Enter The L Word. “The show is a kind of sapphic thirtysomething, about life in Los Angeles for a circle of glamorous female friends who have in common a tremendous drive to succeed,” Bolonik writes. “They’re all dressed up for the American living room with money, looks, style and wit to spare.” And there isn’t a mullet for miles.

“After years of living down our dumpy reputation, perhaps it behooves us to put our best, most made-up faces forward for a change.”

Perhaps. But I, for one, haven’t worn makeup since I tried to be straight for my high school prom.

Still, I can’t deny the show’s growing popularity. Chaiken says she’s delighted with the splash her brainchild has made. Delighted but not surprised. “I think it’s our time,” she says. “People want to hear our stories and no one’s been telling them.

“I think we’ve all been starved to see representations of ourselves.”

Too true. But that brings me back to my original question: do these stories represent me and the people I love?

I’m still not convinced.

***

Just look at the show’s title: The L Word. Does that say out and proudly, uniquely, lesbian to you?

“You think that it’s coy?” Chaiken challenges me. She has already told other interviewers that the title is meant to play on the notion of lesbian invisibility.

Does it play with the notion, or simply perpetuate it? I ask.

“I think we’re taking on the coyness – and everything else – in the title,” she replies.

Of course, it can’t be all things to all people, but “it’s the best title we could find,” she continues. It’s punchy and memorable and “it said all the things we wanted to say, including, ‘Some of us are coy about saying the L word.’

“We’re pretty frank on this show,” she insists. “There may be some choices that we make that, to some people, might appear evasive, but there’s nothing we can’t or won’t do or talk about.”

Besides, she adds, “Most people would have to admit that we’re talking about and portraying things that haven’t really been broached in popular television” before. “I don’t think we’re coy.”

Then why do most of your lesbian sex scenes fall so flat for me? I ask.

“I think only you can answer that question,” she laughs, adding that she thinks some of the scenes are “pretty sexy.”

Well, maybe it is just me (cue the identity crisis), but I think the hottest sex scenes in season one were the straight ones with Tim (Eric Mabius) and his soon-to-come-out girlfriend Jenny (Mia Kirshner). They were raw and hot and desperate, full of rippling muscles, heavy breathing and fairly explicit imagery.

The woman-on-woman action, in contrast, generally lacked intensity, lacked that raw sexual charge. In fact, they seemed a bit self-conscious to me. And they never went far enough.

Could it be that the mostly straight actors fell back into old, familiar patterns and nobody stopped them? Or maybe the powers that be decided to aim for a wider, possibly bi-curious crowd, and deliberately only dabbled in lesbian sex before getting down to the real thing in the safer straight sex scenes.

Even Bette and Tina’s big insemination scene pulled its punch before the climax, scooting safely away from any shuddering, full-body orgasms to an extreme close-up of Tina’s dilating pupils.

“Did the camera shy away?” I ask Chaiken.

“No, the camera didn’t shy away,” she answers firmly. It was an homage to a drug film whose name she can’t recall.

This was “not about prurience,” she insists. “It wasn’t an evasive thing at all.

“What would you have wanted to see?” she asks. “The syringe going into her cervix? It’s not exactly sexy.”

Maybe not, but it’s very, very lesbian. And it doesn’t have to preclude an equally lesbian orgasm in the following frame.

“It’s always a challenge” to shoot a hot sex scene, Chaiken points out. Different things work for different people.

“All I can say is, we try to be frank, we try to be accurate, we try to be erotic, we try to capture the emotion and authenticity of what’s supposed to be going on in that scene. And we try to do our best.

“And I hope that they’re working for people. And if they are – great. And if they’re not, well, we’re going to keep on portraying love and sex because it’s a big part of our storytelling and I hope that people will eventually find what they’re looking for.”

Well, what I’m looking for is simple: authentic, believable lesbians. And I’m still not sold on The L Word. In the sex that they have and the clothes that they wear; in the things that they say and do; in the trips they spontaneously take to party in Palm Springs and the carefree affluence they generally exhibit – do Chaiken’s characters say lesbian to me?

Not really.

I mean, sure, they have their moments. It’s not like the show never makes me smile. Sometimes, it’s even dead-on and lots of fun. Like the time Dana’s friends fanned out through the tennis club to inconspicuously assess her love interest’s likely lesbianism. (Whispered cell phone conversations ensued as they gauged the subject’s finger length, shoe style and size, and other supposedly telltale signs of dykehood.)

Then there was the time Alice (real-life lesbian Leisha Hailey) led a group intervention to nip Bette and Tina’s encroaching dullness in the bud when all they could talk about was their pregnancy.

And the list goes on. I’m not suggesting the show is wholly without merit. It’s not. It’s just that it has such a huge and important void to fill, and so many varied expectations to meet.

Maybe it was doomed to disappoint at least some of us.

“There’s no question that representation is a political act,” Chaiken concludes. “And if we’re helping to establish representation for a group of people who’ve been marginalized, then I will happily embrace that as a cultural contribution.”

So would I. I just wish she’d represent me and the people I love a little more accurately as she re-defines lesbian for the mass consumer.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra