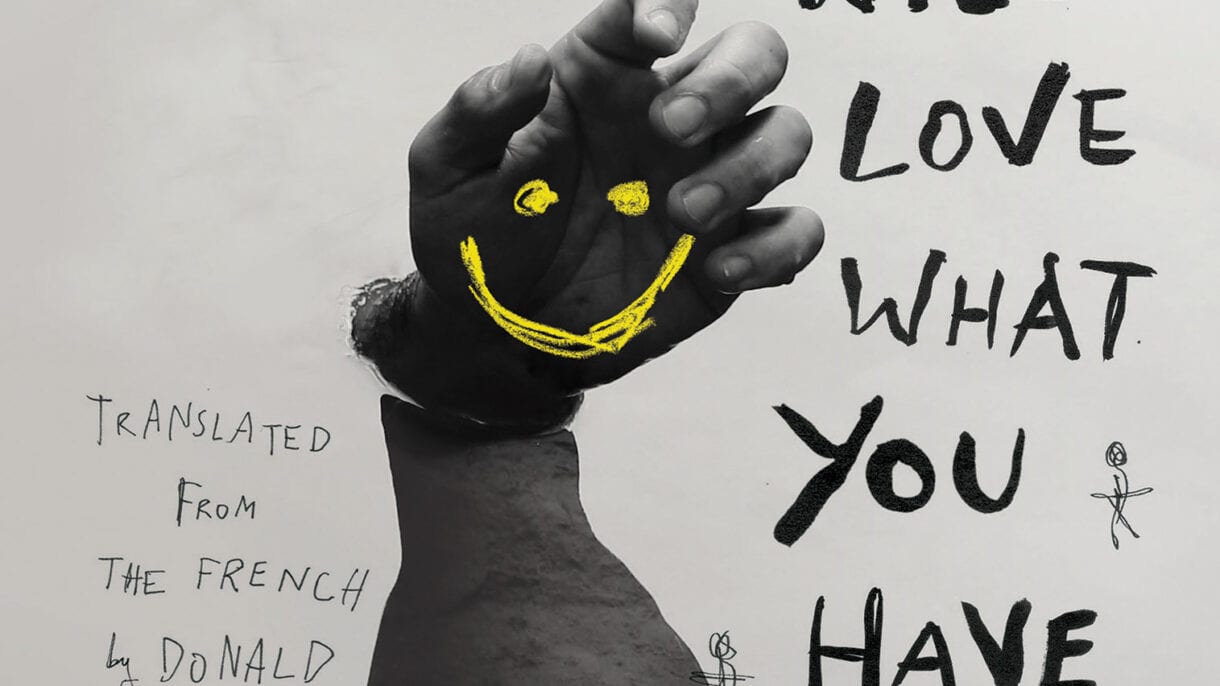

We’ve all thought about blowing up where we come from at one time or another, but author Kevin Lambert does it literally and figuratively in his book You Will Love What You Have Killed. First published in French in 2017, the English translation of his debut came out last month from Biblioasis. In the book, Lambert takes all the rage he felt growing up in the small, insular Quebec city of Chicoutimi (what he calls “the suburb of nothingness”) and sets it on fire, pointing a finger at pretty much everyone for their complicity in failing the town’s youth. “I felt a lot of anger growing up in Chicoutimi,” the 27 year old says on the phone from his home in Montreal, where he’s lived for the past eight years. “At first, when I was a teenager, it was just a raw anger that had no shape. I didn’t know why I was angry. But it was, of course, because the city was so narrow minded and strict and the possibilities there were limited.” Chicoutimi is located in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec, an almost five-hour drive from Montreal. “There was this fear of everything that is not yourself, a fear of people who are not white or heterosexual or Quebecois. It was all linked together. I didn’t only see homophobia. I saw homophobia linked to a general fear of otherness.” You Will Love What You Have Killed is Lambert’s over-the-top reaction (and a warning) to the town that bore him; a big fuck-you-with-finger-up to the system that taught him that the only thing he needed to know about sex was to “wear a condom.” Frenetic and strange, the book tells the story of several of Chicoutimi’s children who die at the hands of the city’s adults. Sometimes it’s an accident, other times it’s murder, but in an odd twist the once-dead children find themselves back at their desks the following week, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with their peers through elementary and high school. It’s ultimately these resurrected kids who plot their revenge on those who were supposed to protect them. At the heart of the story is the narrator, Faldistoire. Sexually abused by his grandfather, he is the angry bullhorn through which readers learn of Chicoutimi’s sins. “Adults project their most terrible perversions onto my silence,” Faldistoire says after a meeting with the school psychologist. “They’ll never be able to explain me completely, to get to the roots of my thoughts, there are no roots and there’s nothing to think. I hope they’ll make themselves crazy trying, that I’ll drive them all to suicide, that I’ll force them to plant bombs, to drink blood, to set Réjean-Tremblay School on fire.” There is an almost breathless quality to Lambert’s writing, a furious run-and-tumble of youthful exuberance in every paragraph with sentences that are chock full of life, wit and sarcasm. And even though Lambert is asking his reader to delve into heavy topics like rape and infanticide, there is still a surprising playfulness and wonderful elements of magic realism and dark humour.

“He’s kind of a wunderkind,” the book’s translator, Donald Winkler, says. The winner of three Governor General’s Literary Awards for Translation, Winkler found it thrilling to be a man in his late seventies tasked with translating the wild fantasies of a young new talent at the start of his career. “This is a classic young guy’s revenge against the establishment story, but he does it in such a brilliant way that keeps you on your toes with all these fast switches and changes of pace. The challenge, in a way, was keeping up with it, reproducing its breakneck momentum and its snap-crackle-and-pop prose in a new language.” Written over a three-year period and published when Lambert was only 24, You Will Love What You Have Killed made a splash when it was first released in French, but not everyone from Chicoutimi appreciated the attention. “People from the region often feel they are not well represented in the media, and because of that they can be chauvinist,” Lambert says. “They’re not very critical of themselves and don’t like it when people are critical of them, especially if it’s coming from Montreal.” Though Lambert was deliberate in sticking his finger in the region’s sore spot, he still made sure not to present everything as black and white. Faldistoire has his faults and is part of the problem, too. Even if some people in his hometown reacted poorly to the depiction, there were others who were thrilled. “Some people didn’t understand why you could hate Chicoutimi, but for others it was a catharsis. Many people feel they have to leave the region, including straight people, for a variety of reasons.”

“Even if it’s a vengeful story, it’s also a way of laughing with, and overstating, my anger.”

Writing the book also proved to be a catharsis for Lambert. “Even if it’s a vengeful story, it’s also a way of laughing with, and overstating, my anger.” Although it deals with biographical moments from his own life, Lambert doesn’t consider the book to be autobiography or autofiction. In fact, he goes out of his way to muddy the waters for the reader. While we are made to wonder if Faldistoire shares some of the author’s real-life experiences, Lambert gives his own name to another character—an adult Kevin Lambert who is a bit of a reckless mess and is personally responsible for the deaths of two of the town’s children. “Even if Faldistoire is the character closest to me,” says Lambert, “the Kevin Lambert character is more telling of my own relationship to my story. And even if the story comes from real things that happened and real memories, you won’t necessarily find the key to everything under the novel. “My manner of writing this book was to use all my memories of suffering and to mask them, to hide them in a false narrative.” It’s no coincidence then we hear the words “fausse histoire” or “false history” in the narrator’s name. “My personal sensibility bends naturally towards ornamentation and fakeness,” Lambert says, citing French novelist and playwright Jean Genet as a major inspiration. “I think that Genet is one of the greatest sentence builders that ever existed. I’m in university now, doing my PhD, so normally I am comfortable talking about books in an academic way. But with Jean Genet, I cannot be academic. My relationship with him is too personal. He is one of the most important figures in queer literature for me.” Genet’s work is more directly referenced in Lambert’s second book, Querelle de Roberval, a story that drops a carbon copy of Genet’s infamous character into a violent Quebec sawmill strike (Winkler is currently translating the book for Biblioasis). That book made Lambert a star in France, where he was nominated for multiple prizes—including the prestigious Prix Médicis, an award that goes to an author whose fame has not yet reached the level of their talent. You can say you heard about him here first.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra