I’ve found writing to be a lot like sex. Like sex, it’s an act of creation, bringing forth whole worlds and beings into the minds of readers. Like sex, it’s an intimate and vulnerable act of sharing pieces of yourself with your readers: hopes, dreams, fears, traumas and how those inform your views on the world and its inhabitants. Like good sex, the best writing is more than just technical mastery of the act; rather, it’s a sincere and honest connection with the reader.

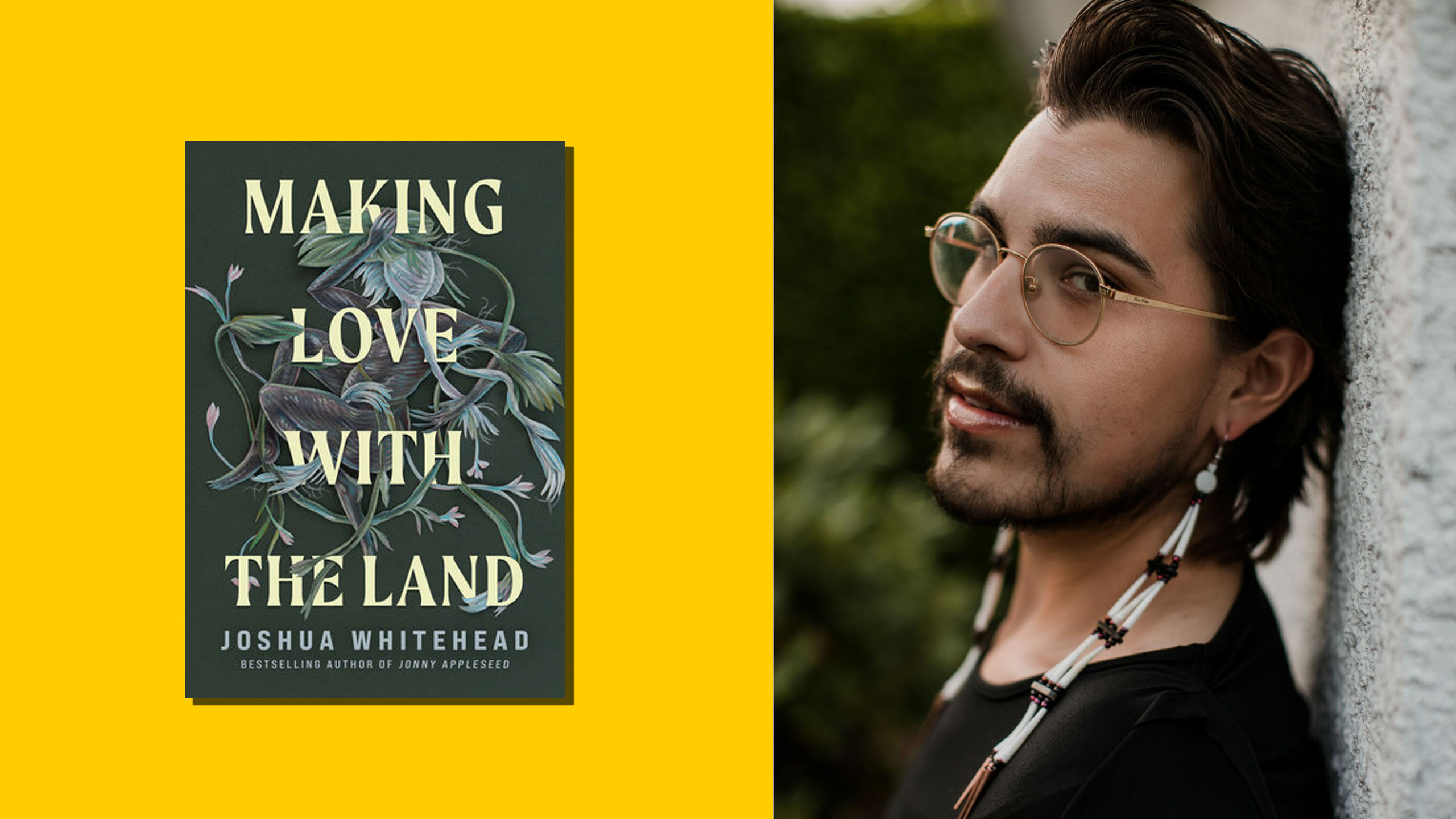

I’ve thought about this often in my work as an editor. I’ve noticed an intimacy as I find ways to work within my clients’ artistic styles, and how it feels similar to learning the body and preferences of a new lover. I was surprised to find the daring literary star Joshua Whitehead sharing similar sentiments in his new book of essays, Making Love with the Land.

“How, then, is storying akin to lovemaking,” Whitehead asks us in one of his essays, “Writing as a Rupture.” Joshua Whitehead (he/him) is a Two-Spirit, Oji-nêhiyaw member of Peguis First Nation. He’s the author of the book of poetry, Full Metal Indigiqueer, and the award-winning novel, Jonny Appleseed, about a cybersex worker trying to exist off the rez. In Making Love with the Land, Whitehead’s essays talk about both works, his time working in academia, as well as his life experiences as a Two-Spirit Native. But that summary does not come close to doing this book justice.

“The book defies colonial conceptions of genre in a way that feels reminiscent to how Two-Spiritedness defies colonial conceptions of queerness.”

Even Whitehead admits this work defies attempts at categorization, blending aspects of autobiography, biography, literary theory and poetry together into each of his essays. This makes Making Love with the Land daringly experimental in form and refreshingly radical in message. Whitehead’s love of poetry brings out the beauty in his discussions of literary theory just as easily as it informs his essays on his family and childhood. There’s a rebellion against colonial expectations of form, which is to say, expectations set forth by the cultures established during colonialism. For this book, that primarily refers to Canada and the United States. As a Native reader, I found this honesty incredibly refreshing. The book defies colonial conceptions of genre in a way that feels reminiscent to how Two-Spiritedness defies colonial conceptions of queerness.

I should also clarify the term Two-Spirit, since the term comes up often throughout Whitehead’s essays. I’ve noticed a lot of well-intentioned but misinformed rhetoric around Two-Spiritedness as a queer identity from non-Natives. Such advocates will mention how Native nations embraced queerness, citing Two-Spiritedness as a queer identity. This is flawed, as queerness and Two-Spiritedness are two entirely different conceptions of the world. The Western concept of queerness is largely an expression of self. Queerness encompasses a wide range of terms devoted to clarifying these experiences as a form of sexuality, gender expression or level of attraction or romanticism a person feels. The word “queer” comes from a reclaimed slur, and implies something strange, and therefore depends upon the continuation heteronormativity for its existence.

By contrast, Two-Spiritedness is an umbrella term denoting a mixture of masculine and feminine sensibilities. It is not only an expression of self, but also about the duty and responsibility the person has to their community. For this reason, it is impossible to be a Two-Spirit as a non-Native, as it requires an intimate understanding of specific Indigenous nation’s traditions to fulfill that community role.

By Western sensibilities, Whitehead would be considered a gay femme man, but he clarifies that Two-Spirit requires an Indigenous conceptualization of the world. He writes:

I identify as Two-Spirit, which means much more than simply my sexual preference within Western ways of knowing, but rather that I am queer, femme/iskwewayi, male/nâpew, and situated this way in relation to my homelands and communities. I state this because queerness, or settler sexualities, has stolen so much from Two-Spiritedness—I am sovereign through what sovereignty calls me.

Whitehead makes it clear that his Two-Spiritedness informs his experiences in the world, but I read his claim to sovereignty to mean that he resists that colonial desire to label and categorize all aspects of our identities. The book, like Whitehead himself, is its own being. Labelling this book as a specific genre would water down that identity.

This steadfast resistance to colonial labels is part of what makes this book stand out amongst other works of Indigenous literature. But Whitehead is clear that he hasn’t arrived at these views and conclusions alone. He’s honest about his influences, citing Lee Maracle’s Memory Serves, Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton’s Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers, and Daniel Heath Justice’s Why Indigenous Literature Matters as helping inform his views and approaches. He uses this acknowledgement to talk about how works don’t exist in vacuums.

“The spirituality of the act is intensely private. Seeing it explicitly mentioned was enough to make me blush. To quote Whitehead, ‘it feels like bringing a camera into a sweat lodge.’”

Further, he’s honest about his process of crafting characters and narrative, a process he acknowledges as sacred. As someone who also makes their living in publishing, I found these insights both valuable and unprecedented. While the act of crafting a story is undeniably deeply personal, I find that the spiritual aspects of the craft are often downplayed, probably because the spirituality of the act, like all other forms of spirituality, are intensely private. Seeing it explicitly mentioned was enough to make me blush. To quote Whitehead, “it feels like bringing a camera into a sweat lodge.”

Whitehead makes explicit that his essays are largely his self-reflections. But rather than lean into the decadence of pure self-exploration, Whitehead draws the reader in, by constantly referring to “you” throughout the work. This inclusion of an ephemeral “you” gives the essays a personalized-bordering-on-intimate tone. “Who is the you I am addressing?” Whitehead writes, comparing this ambiguous “you” to a cherished, but distant lover. His attitudes toward this “you” change with the subject and tone of each essay.

For example, in the opening essay “Who Names the Rez Dog Rez,” he’s sensual and exploratory, “[…] Here, in my bed, beneath fairy lights and vinework, I am beside a you whose chest blazes with similar glory, patch of spirit, bed of dandelion, and I am grazing softly, regurgitant—is this you ‘you’ in my bedsheets when I pool between his thighs?” He concedes, “I am only making love to myself, aren’t I?,” a poetic admission that I took to mean that this intimacy isn’t really about “you,” the reader. Rather, it’s his way of opening up new ideas and pathways in himself.

Later in the book, this reference to “you” is pleading, a request for the reader to truly understand the terror of existing in these dangerous political and environmental end times. “I feel as if I am reaching out to this voidless ‘you’ in order to say, help me, by which I must mean: help us.” As readers, we are drawn into this battle for survival, an appropriate artistic choice as these systems are failing all of us. By the end of the book, it’s downright mournful, as the “you” refers to Whitehead’s former lover during their break up.

At one point he even confesses that “you” are only the fourth person he’s ever confessed a specific battle he’s had in his life. Even now, as this information exists in published form, I hesitate to share that battle without his permission, as this framing implies a level of trust he’s placed upon me as a witness to his traumas.

I find that I come by that trust willingly. After all, this intimacy must be earned by the reader; this book is far from a fast read. It asks you to linger with the thoughts and concepts as one might linger with a new lover. There’s a new vocabulary that he asks you to learn; Whitehead’s work as an assistant professor at the University of Calgary shines through, as he introduces readers to words and practices associated with high literary theory. Meanwhile, the essay “A Geography of Queer Woundings” begins in English and slowly introduces you to Nêhiyawêwin words until you’re flowing back and forth between the two languages. I found myself keeping Google open in the background while reading it, both to translate Nêhiyawêwin words and to look up unfamiliar literary terms.

This isn’t a book that focuses on the topics people often associate with Indigenous nonfiction: the trauma of boarding schools or understandings of Indigenous national histories. Which isn’t to say those subjects go unaddressed. Afterall, his Two-Spiritedness, and thus his Indigeneity, undoubtedly inform his lived experiences, and he credits his family’s hardships to the failures of colonial settler states. But those are details that contribute to the complexity of this work, rather than the focus. Instead, Making Love with the Land places the focus on Whitehead’s relations, to himself, his family, his community, his work and the land itself. And of course to “you,” the reader.

Making Love with the Land stands as a bold statement that Indigenous literature matters. The book is a groundbreaking exploration of form, and a testament to the idea that our stories are so much more than our traumas. I look forward to reading through this book again at length, without the pressure of deadlines looming over my head. This truly is a work that’s meant to savoured.

Nia:wen’kowa ne oká:re, Joshua. A big thank you for your story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra