It’s 10 p.m. My fingers dance around the keyboard of my laptop as I frantically wrap up my outstanding school and work assignments for the day. I’m sitting on a white, fluffy office chair in my small apartment bedroom, the blue light of my computer screen the only light source in the dim room. I send my final email, lean back and exhale the rest of my exhaustion in one long sigh.

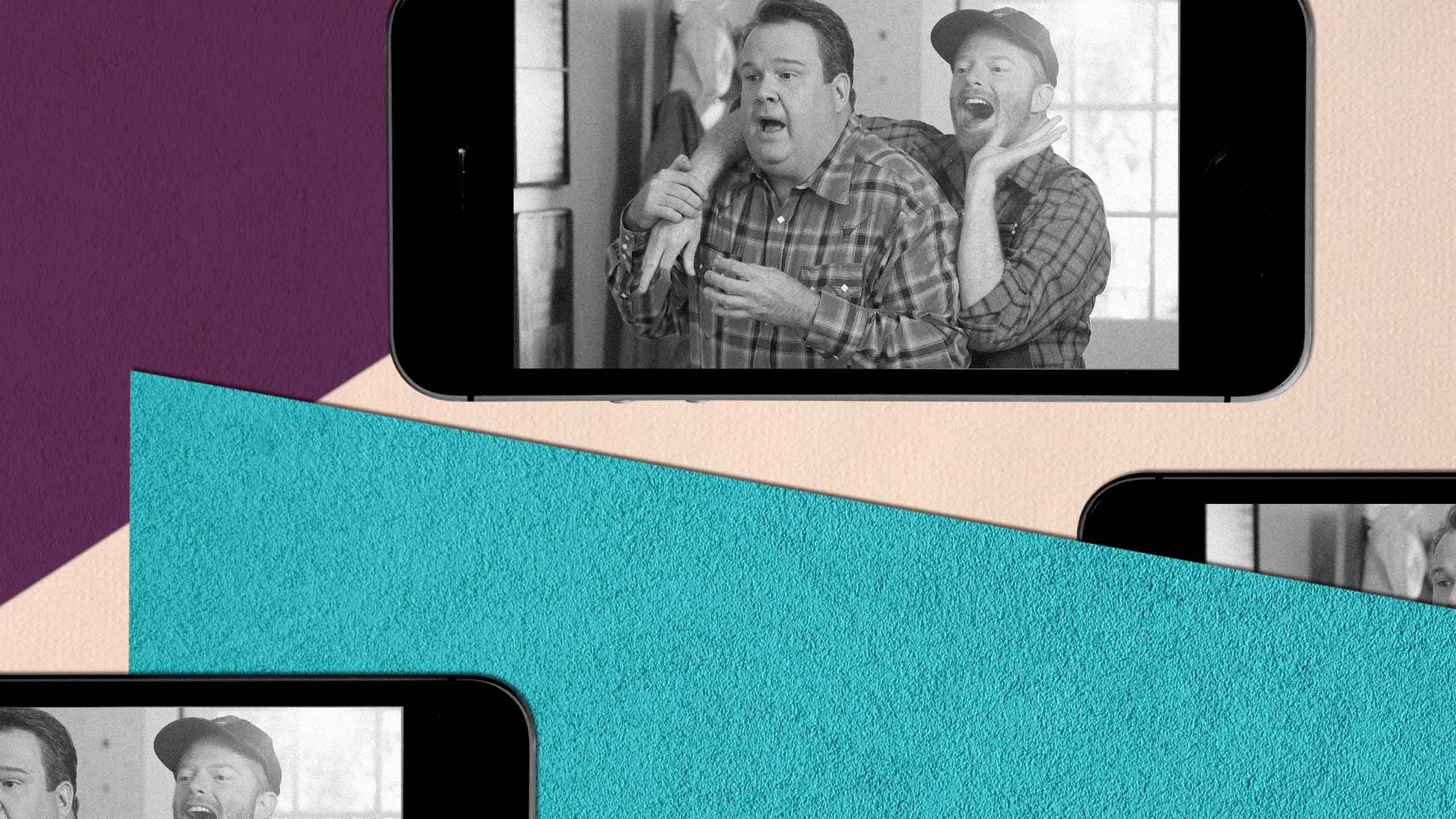

I can’t help but feel anxious as the end of the night approaches. I look up and notice the dry, sad plants on my windowsill above my desk and the full laundry bin in the corner, unavoidable in my periphery. I get up out of the chair and turn around to face my bed, the pink quilted sheets unmade and messy. I crawl in and cocoon them around me as I lay with my back against my headboard. I grab my phone, open YouTube and begin scrolling through my homepage. A “Best Mitch and Cam moments from Modern Family” montage is recommended. I watch the seven-minute video and after a couple of muffled laughs and some happy tears, I’m asleep, free from the usually buoyant anxiety. For me, this routine is queer escapism, freedom from my everyday mundanities.

“If my son was gay, I’d disown him,” my father said, slouched in our worn black leather couch as he flipped through channels. What if it was your daughter? I thought. What about me?

I was 12 when he said that. For years after, I suppressed my queer identity in hopes it would disappear. But a sense of overwhelming discomfort hung over me; my queerness was doing somersaults inside my soul, waiting to be released.

Growing up in a strict Muslim household, queerness seemed to be a myth—a sinful one. And because of my Muslim identity in a predomenantly white Ontario town, there were unspoken barriers that prevented me from connecting to peers and possible queer allies around me. I didn’t have anyone to confide in or relate to in my youth, so I suppressed my queerness completely. Being a queer Muslim person in that town and in my family, I felt like an anomaly. The void of my missing queer identity quickly progressed into a pit of self-hatred and denial. I was constantly fighting the spark I felt when I liked a girl at school or the attraction I felt to a female character in my favourite TV show. I am the only person who feels like this, and there is something wrong with it, my mind insisted.

“The more of this content I consumed, the closer I felt to the people on my screens—and eventually, the more I felt like myself.”

During the time I spent at home in my early teen years, I caught glimpses of gay representation on TV that disparaged the fears and internalized hatred I felt for myself—from watching Ellen DeGeneres be fearlessly out as a television host and seeing Glee’s multiple LGBTQ-identified chatacters to Mitch and Cam on Modern Family embracing each other on screen to sneaking downstairs at midnight and watching reruns of MTV’s 1 Girl 5 Gays. The more of this content I allowed myself to consume, the closer I felt to the people on my screens—and eventually, the more I felt like myself.

That connection to queer content strengthened when, in 2011, my dad surprised me with a new iPhone 3G. At the time, I was unaware of how influential this tool would be in my growth and journey toward self-love and acceptance; but this phone marked the start of my new routine of anxiety-busting queer content consumption.

With the internet at my fingertips, I spent the following years catching up on all of the TV my father was so quick to silence with the press of a button and a censoring retort. I was dying to binge all of RuPaul’s Drag Race (and yes, it changed my life). Seeing characters like Glee’s Brittany and Santana and Naomi and Emily from Skins, I was reminded that queer love can and should be celebrated. I found freedom in cheering on gay protagonists and found solace in watching their resilience, happiness and transparency.

Spending time online in my teens exposed me to the community and content I wasn’t allowed to embrace during my youth. I didn’t know any out gay family members, neighbours or friends. The only time I didn’t feel alone was when I watched queer people and characters onscreen. The pit of self-hatred vanished as the void in my queer identity filled up with support. Watching these actors and internet personalities navigate crushes and experiences made me feel hopeful. Successful LGBTQ2S+ relationships and family dynamics were no longer a myth—they were a beautiful reality.

After consuming this content online for years and finding a growing sense of self-understanding, I started to connect with the community through my phone. Using various apps like Twitter, Vine, YouTube and Instagram, I met queer folks from various locations who fostered a virtual safe space for me to ask questions, share my experiences and feel normal. I was no longer mentally berated by the unknown. Other people like me exist, I thought. And they’re pretty awesome.

Now, almost a decade later, I still find solace in my iPhone. Even as the technology has improved and I’ve moved into my own apartment, that handheld device remains my safe space. No matter where I am physically, I feel the most connected to myself and my identity when I’m supporting or communicating with the community through my screen.

“I feel the most connected to myself and my identity when I’m supporting or communicating with the community through my screen.”

Though I’m not overtaken with internalized homophobia anymore, routine worries about school, bills, work, family (and just about everything else) still seem to vanish with the help of my iPhone. I’m able to find comfort in the back and forth banter of my two favourite gay lead characters. Even on my most stressful days, anxieties that typically dwell over me fade away when I click on a cute queer TV compilation on YouTube.

What my high-school self didn’t understand was the power of my iPhone to bolster my queer identity. I was able to make queer friends using the internet who, to this day, aid in my voyage to self-understanding. Connecting with these people on social media, I was free to be myself and found a community who supports and accepts me for who I am.

Watching queer folks find happiness, love and self-acceptance on my iPhone helped me believe that I’m deserving of those things, too. Now I celebrate myself the way I’ve celebrated them for years.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra