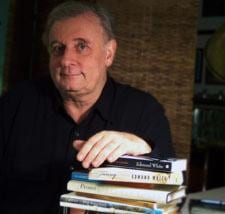

“The most important things in our intimate lives can’t be discussed with strangers, except in books,” Edmund White wrote in his 1982 autobiographical novel The Beautiful Room is Empty. Nearly 30 years later it is an observation he still believes to be true.

“When you have a discussion with a friend or lover there is the benefit of time and context. A book is a conversation where you have one person doing all the talking, you have several hours, not to say days, to get your point across,” he says from his home in New York. In the background an aria and street noise spill into the phone.

“What’s great about a novel is that it creates the exact moment and tells you to whom this is happening and what it means to him or her and I think that’s the way you can actually convey a truth in a context. I believe in contextual morality.”

The famous author is coming to Vancouver on behalf of the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy at UBC. Department chair Dennis Sumara and local author Claire Robson are researching practices of reading and writing memoir as they relate to the navigation of identity by people who are old and queer.

White will also be working with a second group, Owls, also funded by UBC and more central to his visit. Owls is composed of older lesbians who have read several memoirs, including A Boy’s Own Story, and are in the process of writing their own. The six women in the group will have a private meeting with White to discuss his process for writing memoir.

White describes the distinction between autobiographical fiction and memoir as simply “the truth.”

“Autobiographical fiction simplifies the chronology, the dramatic personae, and cast of characters,” he explains. “In an autobiography you can be as eccentric as you really are and describe yourself as a total freak if that’s what you are. In a novel you would be reluctant to do that because no one would be able to identify with it.”

He uses the central character that he based on himself in A Boy’s Own Story as a case in point. In real life White was a straight-A student, wrote an opera by the time he was 14 and had tons of sex by 16. In the book, the protagonist is more like the average gay guy of that age: not a prodigy and timid sexually.

“If you’re writing a novel for a lonely teenager to read in Provo, Utah you don’t want it to be too freaky,” he says. “You would be surprised how something like A Boy’s Own Story frightens young gay people because they think, ‘My god does that mean I have to do all that crap?’”

White compares A Boy’s Own Story to his forthcoming memoir City Boy, due out in October about gay New York in the 1970s.

“It’s not that I want to write a comprehensive picture of New York in the 1970s but I wanted to write about my New York in the ’70s which, in the immediate aftermath of Stonewall, was very gay as well as sexually liberated.”

Back then, he says, New York was bankrupt, extremely dangerous and probably outstripped Paris, London or San Paolo for excitement. Pre-AIDS, New York was the cultural capital of the world because it was home to the greatest writers, the greatest painters, and the greatest composers — partly because it was cheap.

“When you’re writing about that, you’re trying to keep all those topics in mind and trying to tell the story through various personalities, famous or not, whom you happened to know. There’s no plot.”

White says he and the other members of the writing group the Violet Quill (that included Andrew Holleran and Felice Picano) had posterity in mind when they were writing their novels in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

“We were very conscious of doing something new which was writing gay fiction for gay readers,” White says. “People had written gay novels before us but they had been mainly very apologetic novels addressed mainly to straight readers. It was sort of like ‘please pity us we’re so sick.’ We wrote for the initiated.”

Although the Violet Quill didn’t have as many readers as someone like John Updike, White says their audience really remembered their work since it was unlike anything they had ever read before.

“People really got their sense of identity from books. Gay bookstores were like community centres and gay writers were sort of like gay spokespeople. Of course all that has changed.”

White says the closing of gay bookstores has had a tremendous effect on the gay community in New York.

“The great thing about gay bookshops is that they provided a non-drinking context for gay and lesbian people to meet. And that’s another important thing: gay men could meet lesbians and vice versa, whereas in the bars in a big city, that seldom happens. Bookstores are great because they give a community centre context that is completely missing in the bars.”

When asked if all lives deserve a memoir, White holds up the Bronte sisters as the standard-bearers for boring people who were able to turn out books full of torment and excitement. He is convinced that Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights is based on Emily Bronte’s dog.

“I think there’s enough happening in every life to provide the material for the most dramatic and romantic novels imaginable if you’re creative enough.”

He adds that the problem with blogs is that there are more people writing them then reading them.

“I suppose if everybody started writing their memoirs there would be no one reading them,” he says. “Maybe there should be two separate human races: One to read and one to write.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra