Credit: Matt Mills

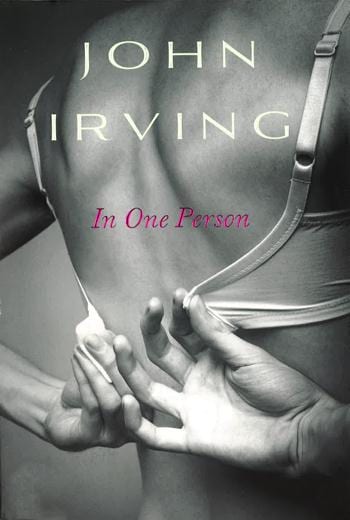

John Irving became a household name with his 1978 novel, The World According to Garp. He solidified that success with A Prayer for Owen Meany, The Hotel New Hampshire, The Cider House Rules and many others. He has, for those works, conjured characters of variously ambiguous gender and sexuality, but he’s never published a novel in which sexual outlaws and the glorious sexual and gender differences among people are centrally featured. He’s never published a truly queer story; that is, until now. His 13th novel, In One Person, due out on May 8, is just that.

Readers first meet protagonist Billy Abbott in 1955, when he is a 13-year-old budding writer and sexual being who finds himself almost overwhelmingly attracted to his librarian Miss Frost, an older, transgender woman. When asked by Miss Frost what sort of stories he would most like to read, Billy replies, “Do you know any novels about young people who have dangerous crushes, crushes on the wrong people?”

Billy’s crushes develop, including one that comes with a desire to fuck the star bully of his school wrestling team. Billy and Miss Frost become closer in the following years until Billy graduates from high school.

As he matures, Billy self-identifies as bisexual, rejects monogamy, and has sexual and romantic relationships with men, women and MTF trans people. We find him in LA in the late ’60s; he lives some years immersed in the gay culture of ’70s New York and some years more in gender- and sexually fluid Vienna. He even briefly visits a dying friend at Toronto’s Casey House. He returns in the end to live in his hometown, First Sister, Vermont, the setting for his formative years and early friendship with Miss Frost. Though obviously not without its tragedies, Billy’s is a meaningful, industrious and seemingly satisfying life.

Through his characters, Irving demonstrates a startlingly sophisticated understanding of human sexuality: that it is as diverse as individuality. The descriptions – written in the first person – of Billy’s lusts, fears, hopes, peeves and regrets will likely resonate especially well with gay and bisexual men. It’s also a hot read for anyone interested in the intersections of gender and sexuality. Life is hard in reality and perhaps harder in fiction, yet Irving has a way of presenting the characters of In One Person as complex and nuanced human beings; sometimes victimized but never accepting “victim” as an identity. There is dignity.

“People are so very different and our sexual identities matter, especially when they are hard to earn, especially when we have been made to feel that we are a minority and we have to struggle to assert who we are,” says Irving in a face-to-face interview with Xtra. “Miss Frost, I think, is also right that it’s not for other people to put those labels on us . . . That’s what she means when she says, ‘Don’t put a label on me. Don’t make me a category before you get to know me.’ . . . Both sexuality and gender are mutable.”

In One Person, as a story about sexual differences among people, has real potential to help effect positive change for gay and trans people, especially in the US. This is the novel I selfishly wish Irving had written 25 years ago. He says he’s had the sketch for it in his mind, along with outlines for several other stories, for more than 12 years. But, he adds, one of the factors that pushed In One Person over the threshold from idea to publication is his son, Everett.

“I did not know when I laid out the architecture for this story that I would have a gay son,” Irving says. “When I began writing this book in 2009, I very much knew that my youngest son is gay. I was very proud of him for coming out. While it would be utter bullshit to say I wrote In One Person because I have a gay son, I was very much aware of having him as my ideal reader. He knows it very well: the person I most wanted to read this book is Everett.”

Check out Xtra‘s video interview with Irving, as well as Irving’s reading from In One Person below:

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra