The early ’90s signalled a shift in cinema and its representation of queer people. From Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together to the Wachowskis’ Bound, meditative and carnal queer narratives were becoming more common on theatre screens. But ahead of them all came a little film called The Living End.

Beginning with a title card that reads “an irresponsible movie by gregg araki,” The Living End debuted 30 years ago in 1992. While it was Araki’s third feature—after Three Bewildered People in the Night and The Long Weekend (O’ Despair)—it’s the film that launched his professional career. It was screened at Sundance and was subsequently nominated for the festival’s Grand Jury Prize, losing to Alexandre Rockwell’s In the Soup. The film’s unabashed contempt for the state of America in the ’90s, as well as its radical display of HIV-positive life, makes for a groundbreaking piece of art.

During Canada’s first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, I watched The Living End for the first time. The friends I was attending university with went home, leaving me alone in the city. With the world crumbling around me and politicians unsure of what to do, I stayed in my room and watched movies. Gregg Araki’s 2004 film Mysterious Skin had long been one of my favourites, so I decided to marathon his filmography. As someone with a parent who was HIV-positive, I was moved to see this diagnosis portrayed with such compassion. In late 2022, as the world continues to grapple with duelling outbreaks of COVID-19 and monkeypox, both of which continue to disproportionately affect already marginalized communities, the film’s message continues to be poignant.

It begins with one of its protagonists, Luke (Mike Dytri), spray-painting “FUCK THE WORLD” on a graffiti-splashed mural, hinting at the character’s doomed view of the world around him. We are then introduced to our other protagonist, Jon (Craig Gilmore), a film critic who has recently been diagnosed with HIV. The two characters meet after Luke has shot—and presumably killed—three gaybashers, and runs headfirst into Jon’s car.

Later, when Jon timidly admits his new diagnosis, Luke indifferently welcomes him “to the club.” The two are widely different, but their shared health condition brings them closer. Luke is clearly a drifter, moving from one place to another, so he doesn’t have anyone in his life. Jon, on the other hand, seems well connected, but he’s too ashamed to tell anyone in his life he’s HIV-positive.

In the early ’90s, HIV-positive men were still looked upon with the disdain that was present when the illness surged in the ’80s. In 1992, the year the film was released, HIV had become the leading cause of death for men aged 25 to 44 in the U.S. Thirty years on in 2022, undetectable HIV-positive people are still being treated unfairly in the justice system. Araki handled the topic empathetically, allowing Jon and Luke to unravel like any other person would under stressful circumstances.

The sex scenes in the film are tense with not just sensuality, but anger. There’s a pivotal scene in the middle of the film, where Jon and Luke have unprotected sex in the shower. It’s raw, visceral and everything that made the queer cinema of the ’90s so intoxicating. The importance of this scene may have been lost on audiences back then (Araki stated that the audience at Sundance was “outraged”), but 30 years later, it feels like an act of protest within itself.

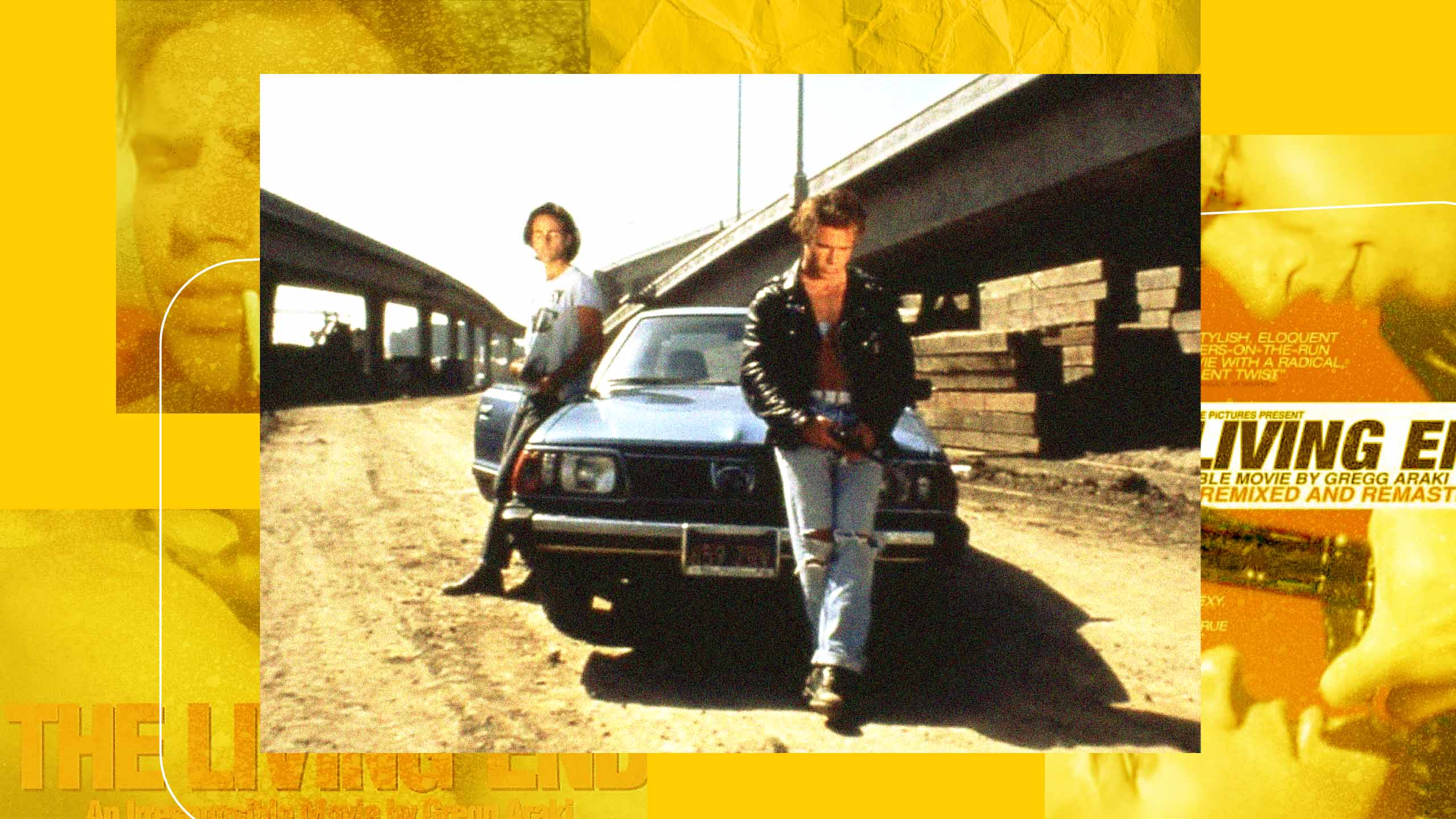

Jon and Luke take off on their Thelma and Louise-style road trip after they kill a homophobic cop. It’s punk rock in the most Araki way, like the sticker that embellishes Luke’s car, which reads: “CHOOSE DEATH.” Rather than wallow in self-pity, they might as well hate the world as much as it hates them. At one point, Luke jokes that he and Jon should “hold [President George H.W.] Bush at gunpoint, inject him with a syringe full of [their] blood…. How much you wanna bet they’d have a magic cure by tomorrow?” Hate masks the anguish that both men carry on their shoulders, yet there’s a catharsis that comes along with listening to these outpourings.

Araki’s unabashed empathy for his two protagonists weaves a film that’s an ode to gay euphoria and turns the road trip genre on its head. Jon and Luke find understanding and love within each other, which isn’t something two HIV-positive men in the ’90s would have found from much of society. Their love for each other outweighs the reality of their illness, and also the hate they’ve encountered in their lives.

If this was a modern film from the last decade, one of the two men might be a victim of the “bury your gays” trope, a trope that is regularly used in television and film, which establishes an LGBTG2S+ couple, only to kill one of them off. Instead, The Living End ends with a shot of Jon and Luke embracing in front of a beautiful sunset. As their story comes to an end for the audience, it seems for them that their new lives have just begun. They are flawed individuals, but Araki maintains that they deserve a happy ending just like anyone else.

While I couldn’t have known what the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic would look like in 2022, I was aware of the discrepancies. As an essential worker who is also immunocompromised, I was not given the grace of time off or offered the chance to work from home. Now, almost three years after the first lockdown, The Living End feels even more poignant.

COVID and its long-withstanding symptoms aren’t the only thing reminiscent of the themes addressed in Araki’s film, though, as the monkeypox outbreak earlier this year shined a light on stigmas that still affect gay men decades later. During a period that’s already been fraught with anti-LGBTQ2S+ logic, the framing of monkeypox as a “gay virus” felt like the government abandoning those who contracted the disease. It is no different than the ways immunocompromised people have been left to their own devices, but the framing in regard to monkeypox is just as dangerous as it was in the height of the AIDS epidemic.

While it begins with an in-joke title card that’s present in most of Araki’s early films, the film closes on a more sombre note, reading: “Dedicated to [musician] Craig Lee … and the hundreds of thousands who’ve died and the hundreds of thousands of more who will die because of a big white house full of republican fuckheads.” With this final declaration, Gregg Araki makes his audience look in on themselves, and whether it was at the film’s Sundance premiere, or 30 years later, asks his viewers to look at the real villains of this story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra