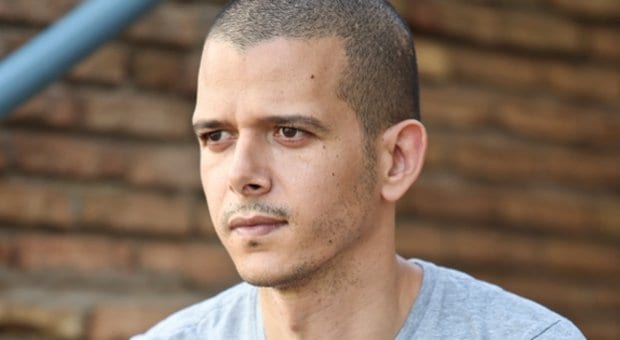

Abdellah Taïa Credit: Courtesy of Abdellah Taïa

The first Arab writer to publicly declare his homosexuality, Abdellah Taïa, grew up in Rabat, Morocco, where poverty and queerness both stunted and stoked his literary ambitions.

Today, as he edges into his 40s, his work has become a necessary, and perhaps unique, bridge between the Arab world and the West.

To the English-speaking world, his best-known work is his autobiographical novel Salvation Army — a brief and heart-wrenching account of his coming-of-age and eventual departure from Morocco. By speaking unabashedly about sex tourists, the latent sexuality of invisible populations, and his first contacts with a bewildering Europe, Taïa scandalized the Moroccan press even while he won international acclaim.

The English translation of his new novel, Infidels, will be published this spring. On Oct 23 he participates in the Beyond Queer event at the Vancouver International Writers Festival.

Xtra: Your Wikipedia page says you’ve been in self-imposed exile from Morocco since 1998. Is that what it feels like? Exile?

Abdellah Taïa: To be honest, I’m not totally comfortable with the expression “self-exiled.” But I did decide, when I was 13, to go one day to Paris in order to be who I am: a free individual.

Why Paris?

Because this city represented the idea of freedom in Morocco [Morocco was colonized by France from 1912 to 1956]. Even in the very poor world I lived in, Paris stood for freedom.

Life is a conscious choice. You just know where you have to go, and you do what it takes. Morocco couldn’t give me the possibilities to be, just to be. There, poverty was my trademark. The young and naive gay boy I was at that time understood this very essential truth: in order to grow up, you have to leave your family, your city and your country.

Now Paris has become my battlefield. Nothing is easy in this city, but you can fight for something. And I love that, to fight.

Being gay has become integral to your identity as a writer. Do you think this will change as your career develops?

No, this will never change. I create from a world that I know very intimately — what’s happening inside of me. Homosexuality is here, in me, in that world. But homosexuality is not my subject; it’s a subject for everyone, even for heterosexuals. I don’t say to myself that I have to write about homosexuality. This very important part of me simply comes out every time I write, in a very natural way.

And that gay identity intersects with class and cultural background. All these parts of you sort of run into each other in your writing. Is there a hierarchy, do you think, between these aspects of identity?

There’s no hierarchy at all. Never. There’s a lot of chaos, in my head and on the paper. Everything is mixed up: politics, sexuality, love, social problems… What’s very important for me is to succeed in finding the right form for this endless chaos. To find a little phrase with a certain rhythm. Not to be descriptive, but to be poetic. And to never, never let go until the end of the story.

In Salvation Army the protagonist seems to have a driving ambition to “become,” to achieve his potential, both sexually and professionally. This made me wonder about your own sense of ambition.

Well, I think one has to be ambitious. Obsessed with things, ideas, projects. Otherwise nothing happens. I’m not interested in money or having some great house with great furniture. But I want to make a good book, a good film, to live an inspirational love story with someone, a man older than me.

Where did your ambition first become real?

When I was 22; I founded a literary circle with three Moroccan friends from the University Mohamed V [in Rabat], where I was studying French literature. We called it Le Cercle Littéraire de l’Océan. We met once a month and brought our stories, which we wrote in French. This was the biggest experience of my life: I understood there that I could do something, create something.

We were just poor students, but we managed to give to ourselves the legitimacy to talk about literature, about writing, theories. Everything I wrote in my books later came from that literary circle.

You speak Arabic, French, English and Spanish. What language do you dream in?

I dream and write in French, with a taste of Arabic. But Arabic dominates the languages in my head.

Do you think something is always lost when your meaning, your writing, jumps from one language to the next?

Well, I don’t think humans have invented a language that can express everything they feel and want to say. I always write with the feeling that something is missing, forever lost, without me knowing what it is.

Abdellah Taïa

Vancouver International Writers Festival, Beyond Queer Program

Wed, Oct 23, 8pm

Studio 1398, 1398 Cartwright St

writersfest.bc.ca

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra