The Wonder Woman comics from the 1940s are rife with BDSM. On almost every page there’s kidnap, slavery or bondage; she (or some other woman) is bound, chained, manacled, tied, has her eyes and mouth taped shut, is gagged, caged, shackled, hogtied or even leashed and forced to crawl on the ground. When things got really out of hand, Maxwell Charles Gaines, the comic’s publisher, sent a memo to William Moulton Marston, the heroine’s creator, advising him to “cut down on the use of chains by at least 50 to 75 percent.” Marston refused.

Marston created Wonder Woman as an example for children and young people of “strong, free, courageous womanhood” in order to “combat the idea that women are inferior to men.” Marston was an ardent feminist, and the bondage in Wonder Woman is reminiscent of symbolism from the women’s suffrage movement — women are restrained and gagged to highlight their lack of rights — but it’s clear there was something else going on there, too.

In 1915, Marston married Elizabeth Holloway, a feminist and recent graduate of Mount Holyoke College. They both graduated from law school — he from Harvard, she from Boston University — in 1918. That year, Marston also became attached to another woman, Marjorie W Huntley, who enjoyed being chained — what she called “love binding.” The following year all three became an item for a time.

Marston got his PhD from Harvard in 1921. His dissertation focused on lie detection, and he is often credited with the invention of the lie detector. Later, he would imbue Wonder Woman with this ability in the form of her Lasso of Truth.

In 1925, while teaching at Tufts University, he fell in love with one of his students, Olive Byrne (whose mother and aunt, Ethyl Byrne and Margaret Sanger, had opened the first birth-control clinic in the United States in 1916).

Around this time, Marston took up the study of sex. Some of his subjects were men incarcerated in Texas, and he became particularly intrigued by “the homo-sexual relationships inevitable in prison life.” Based on his observations, he argued that there were four primary emotions: dominance, compliance, inducement and submission. At Tufts he focused on “captivation,” which he defined as “an essential constituent of sadistic teasing or torturing of weaker human beings or animals.”

Thinking Marston might be interested in the doings at her sorority, Byrne brought him along to their “Baby Party,” where freshman pledges were dressed as babies, blindfolded, had their arms tied behind them and were compelled by stick-wielding sophomores to perform tasks. After the party, Marston and Byrne interviewed the participants, finding that “nearly all the sophomores reported excited pleasantness of captivation emotion throughout the party.”

In 1926, Byrne moved in with Marston and Holloway (with Huntley joining on occasion), and there was, as Holloway later said, “love making for all.” Holloway later claimed that the structure of their threesome had been worked out at pseudo-religious sex parties the three had attended, where people would organize themselves into “Love Units” comprising a Love Leader, Mistress and Love Girl.

In 1928, Marston published Emotions of Normal People, a book that defends homosexuality, transvestitism, fetishism and sadomasochism.

They tried to hide their polyamorous relationship but didn’t succeed, and the revelation ruined Marston’s academic career. Over the next few years, he worked on various projects, achieving a kind of notoriety. Then Gaines, the publisher of Superman, came knocking. He was worried about what critics were saying about Superman — that he was dangerous and fascist — and asked Marston, “Do you think these fantastic comics are good reading for children?” Marston eased his worries. Further, he argued that if Gaines published a comic containing a female superhero it would help silence the critics.

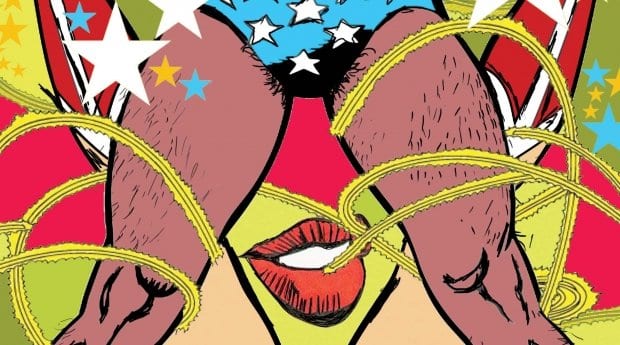

Gaines hired Marston, who created a female superhero like something out of feminist utopian fiction: an Amazon. Debuting in 1941 in All-Star Comics No 8, Wonder Woman wore a golden tiara, red bustier, blue shorts and had pouty lips. Marston may have intended to create the ultimate feminist figure, but what he produced — a strong woman with a truth-evoking rope, knee-high red leather boots and a tendency to get chained up — was informed also by his various interests and kinks.

For more, I highly recommend reading The Secret History of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore.

History Boys appears in every issue of Xtra and every two weeks online.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra