What happens after you meet the love of your life? In 2012, Benjamin Alire Sáenz introduced us to Aristotle and Dante in the YA novel Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe, making us fall in love with the two Mexican-American boys as they both discovered their sexuality and love for each other. The book slowly became a massive success, racking up award after award for its portrayal of two brown boys in 1987 in the borderlands of El Paso, Texas. Sáenz credits much of the book’s success to the fans: “They sold it to each other. It was sold mouth to mouth, hand to hand.”

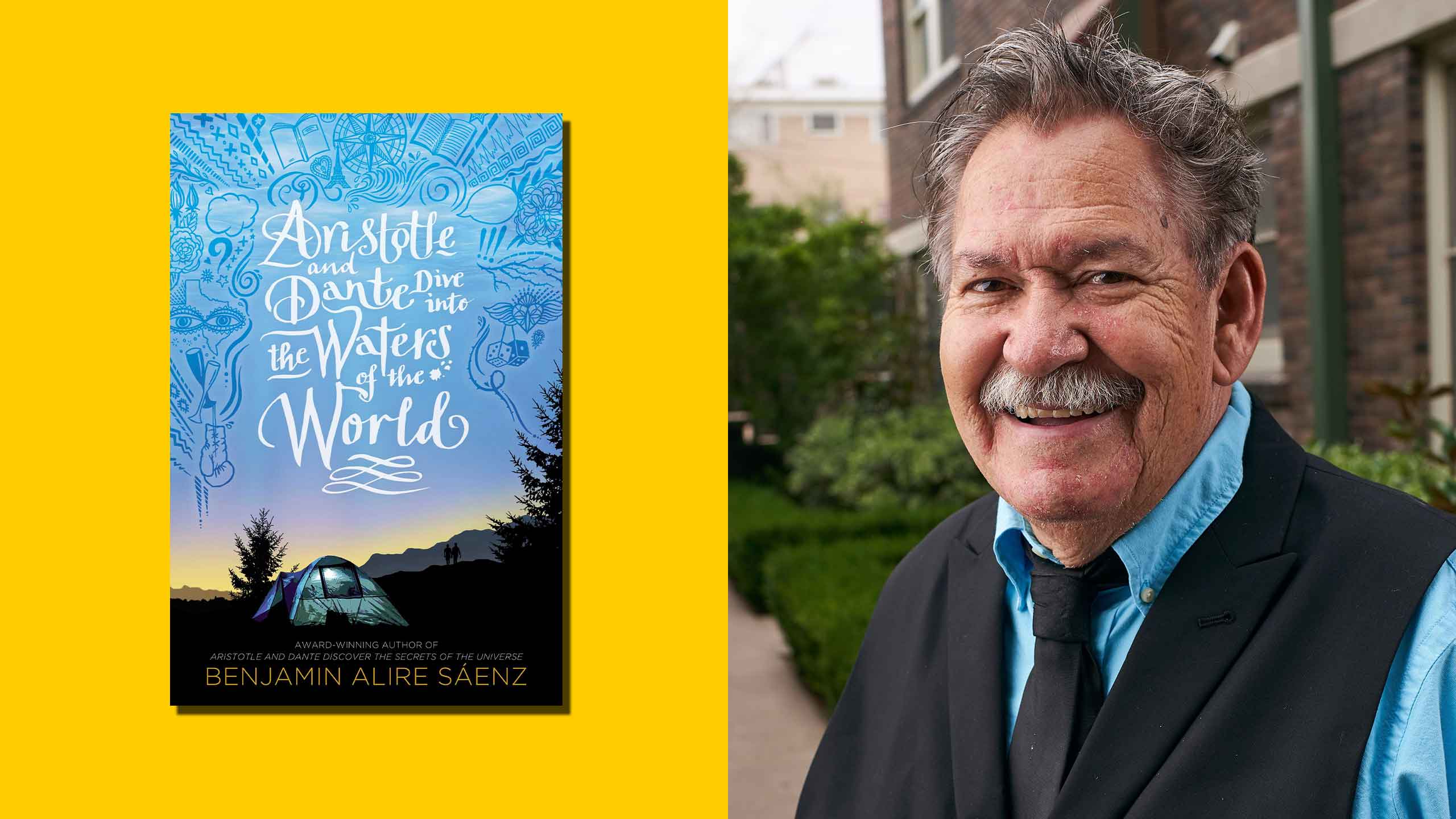

Now, nine years later, Sáenz returns with a sequel, Aristotle and Dante Discover the Waters of the World, out Oct. 12. Picking up where the last book left off, Ari and Dante have come to tentatively accept their sexualities and love for each other. But now what?

The sequel pops the bubble of a neat “happily ever after,” to explore the difficulties of both sustaining a relationship and finding a place in a wider world that may not always want or accept you. Set in the years 1988 to ’89, the book tackles the beginning of the AIDS crisis; its characters not only witness a disease that will undoubtedly touch their lives but also the homophobia and racism that made the period so devastating.

Ahead of the novel’s release, Xtra spoke with Sáenz about crafting this love story almost a decade after its first iteration.

When you wrote the first book, did you have a sequel in mind? And if not, when did the sequel become something that you wanted to do?

No, not at all. When I write a book, I write a book. I’ve never written a sequel nor have I ever intended to write a sequel to any of my books. All of my books have sort of an open-ended quality to them, and I think that’s about right because I think in life, there are no closures. There’s always unfinished business somewhere, particularly with relationships. I really feel that one of the reasons I wrote the sequel is because I had a couple of regrets. One of them was that I completely left out the AIDS epidemic [in the first book]. That really bothered me. On the one hand, [Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe] was about turning inward and two boys discovering themselves and their identity. So there was no social, cultural or political background to it because it didn’t seem necessary. But I thought I should have done something with [the AIDS epidemic] because it was a very, very important epic in my life. I lost my mentor Arturo Islas, a writer and professor at Stanford. I lost my older brother Donaciano Sanchez, and I lost one of my closest friends Norman Campbell Robertson. And the U.S. government didn’t give a damn. Never has the gay community been more hated, because they were afraid [of us]. Even more than that though, all over the world, gays were protesting and raising their voices. The world discovered how many of us there were, and that scared the hell out of them. I wanted that epidemic—which very much mirrors, in some ways, [the COVID-19] pandemic—to be a part of Ari and Dante’s story.

You deal with a number of big, complicated issues in this book: racism, gender and sexual identity, incarceration, veterans issues, government failure. What led you to decide to revisit these characters and have them navigate these problems?

[Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe] ended where the relationship begins. It is one thing to fall in love. It is quite another thing to stay in love. So I wanted to have them navigate through that relationship. A relationship solely turned in on itself will destroy itself. The first book was a book that turned inward and the sequel is a book that turns outwards toward the world that they live in that causes them pain. But the world doesn’t belong to one person alone. And I think part of the story of this book is just that. We have to embrace our own humanity and [the role] we play in the universe, and that we matter more to the universe than we believe we do. And that we are also responsible to the universe for the things we do.

I understand you’re in your 60s, which means that you must have been in your 30s in the late 80s, the time period the novel is set. What was it like to revisit an era of great chaos and loss through the perspective of teenage characters?

I just turned 67 this past August, so it was very difficult to write like a 16 or 17 year old. What would they know? What would they ask? How do they understand this? Ari and Dante are really smart and articulate and aware, but they don’t know anything. They are just discovering things. There is an innocence and a tenderness to them that is very vulnerable. They are aware of the crisis because it’s going on around them and I knew they were scared and don’t feel safe, but they are trying to figure this out and I needed to wonder what that would be like. I tried to do that in the book. That was the problem I had to solve as I wrote the novel.

Most of the book is from Ari’s point of view but you also include sections of Ari writing a letter to Dante in his journal. Describe for me the intention there.

We’re different when we write. People used to write letters to each other and those letters were very intimate; they were telling secrets in those letters. Ari reveals a lot of what he feels for Dante that he would never tell him face to face in those journals. Ari loves and feels and articulates that just as much as Dante, but we see that in Ari’s letters in his journal. And I like that because he’s very vulnerable and we get to know him better. But he would never say those things to Dante. But he does feel them.

This book took almost nine years to complete and I’m really curious about what that process was like for you?

I wrote the majority of it during the [early part of] the pandemic because I really changed my mind about the book and what I was going to say, and I’m very grateful for that. I think I wrote the book I wanted to write. I was really heartbroken at the beginning of the pandemic because my dog died in my arms. It was painful for me. I was so sad. And so I just jumped into the book. I just started writing and writing and it just kind of came to me and it helped ease my pain. But one of the reasons why it also took so long for me to write is because I’m also a painter and a poet and a teacher. I was painting a lot during this period. I love painting because I don’t need to use words. Words can see you, but they can also clutter your life. There were so many words and I got tired of them and they wore me out.

“We are a part of the world, we are a part of the universe, we are all connected to each other, whether we like it or not, and we are responsible to one another.”

I think that I was trying to discover myself and who I am, discover what is this thing to be human. That helped the writing process; I like to write characters that are real.

What do you hope young readers—and just readers in general—will take away from this story?

We are a part of the world, we are a part of the universe, we are all connected to each other, whether we like it or not, and we are responsible to one another. It’s so difficult to have conversations with each other when we have differences. The world is hard but we somehow have to find a way to stay soft and be forgiving. We need to try to be good to one another and be kinder. I think that’s very important. I want us to all understand, including me, that we can be better people.

This story is published with support from the Ken Popert Media Fellowship program.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra