“Our body isour own language,” smiles Vancouver choreographer and dancer Wen Wei Wang. Cross-legged in the sun-drenched studio at the Scotiabank Dance Centre, Wang turns his head to stare out the window a moment. “That’s why I dance,” he says. “With dance you can tell your own story.”

Wang is one of several queer dancers telling their stories at Vancouver’s International Dance Festival (VIDF), Mar 8-26, at the Roundhouse Community Centre. The festival features local, national and international artists, and includes a series of workshops and free performances.

Wang began training in China at the age of eight and later travelled to Beijing to study choreography in 1989. His education spanned a time in Chinese history that was “very restricted.” Enmeshed in the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s, Wang’s initial dance lessons were highly censored.

“You were not allowed to perform any Western cultural work,” he recalls. What’s more, in such an environment, “you don’t have the desire.”

Which is what makes cultural exchange, and the formation of identity, so crucial to Wang’s current practice.

“Here, you are told to have your own mind,” says Wang, of Vancouver and North America.

“You can’t be 100 percent who you are anywhere,” he admits, but when it comes to his sexuality, Wang feels his life has opened up since his move.

In China, he says, “I never allowed myself to be different. Here you can choose your life. There, they can send you to jail.”

Last year, Wang created his own dance company, Wen Wei Dance. With its proposed growth next year to a core of 10 dancers, Wang has committed himself to fostering a truly contemporary dance company in Vancouver.

“All new work,” Wang beams. “I have a large dream for this country.”

The connections (and frictions) between Chinese and Canadian culture fed into the creation of Wen Wei Dance. And Wang’s double sense of difference-as an immigrant and a gay man-means his company will be fuelled by a keen respect for culture shock.

Wang’s performance isn’t the only queer aesthetic on stage at this year’s dance festival. Québec’s Lucie Grégoire is also slated to dance at the VIDF, with a gender-fuck piece titled Eye. Choreographed by Yoshito Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata (the progenitor of butoh), Eye has a woman dancer dress in a man’s three-piece suit and struggle to cross the gender binary wasteland through movement.

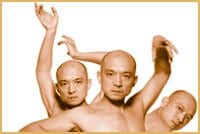

And the Festival kicked off with Vancouver’s own Kokoro Dance, which joined Poland’s Silesian Dance Theatre to co-produce Tutaj Tam/Here to There. Like Wang and Grégoire’s works, the piece transgressed societal boundaries. Its male and female performers sported shaved heads to obliterate the ease of gender differentiation.

As Wang sees it, “the body on stage is a new world.”

Can a continent sway inside a dancer’s body? “Sometimes I feel I’m not in the real world,” Wang replies. “What is real? What is a dream?”

He has a history of confusing the two. His path through life, as he presents it on stage, is one that witnesses a constant unrest, a movement across borderlines. His dances are always searching for the undiscovered country.

“In any creative act,” he insists, “you can never feel comfortable.” So he moves on.

“It’s about the way,” he sums up. And if Wang begins to sound like a Taoist here, it’s because he is one.

For his part in this year’s dance festival, Wang is unveiling the world premiere of his company’s solo, 70-minute piece, One Man’s…

One man’s what, exactly, is anyone’s guess. “That’s why you come to the theatre!” he teases.

And what can audiences expect to see at the Roundhouse theatre? “Open your mind, don’t ask questions too soon,” cautions Wang. The piece incorporates film, speech, singing, elaborate sets and, of course, dance to ensure those questions (when we do ask them) are awe-inspired.

The “new world” Wang speaks of is an inviting one. “You’re in there,” he smiles. “You want to know it.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra