You didn’t want to look.

When you bought the ticket, you knew the movie was going to be scary, but you had to see it for yourself. Kind of. Peeking between your fingers.

You couldn’t look . . . but you couldn’t look away, either.

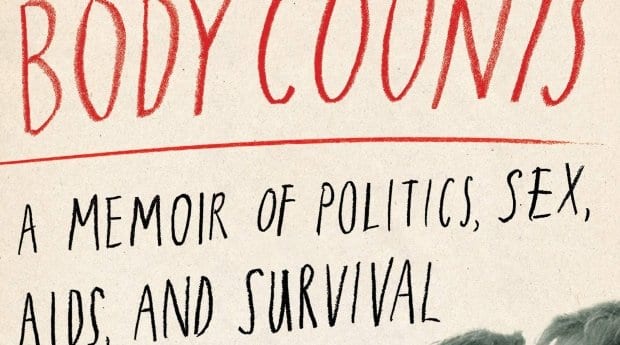

In the early 1980s, when AIDS was barely understood, Sean Strub decided something similar: he’s gay and had engaged in risky behaviour, but he didn’t want to be tested. In his book Body Counts, he writes about HIV and the United States Congress and how they set the course of his life.

At a time when most kids want to be cowboys or ballerinas, Sean Strub wanted to be a politician. He was obsessed with politics and, by time he moved to Washington to work as an elevator operator in the Capitol building, he was also fixated on losing his virginity.

For years, Strub had hoped his attraction to men was “a phase that might pass.” It was 1976, and being gay was scary for a small-town Iowa City boy. He wasn’t even sure if sex between men was possible, but after he moved to Washington and then to New York, it didn’t take long to find out.

“If Washington was a staging area for my life,” Strub says, “New York was the destination.”

Being a 20-something gay man in the Big Apple was exciting and liberating. Strub found a thriving, politically strong LGBT community, immersed himself in activism and discovered gay bars, bathhouses and an abundance of available men with whom he “was playing catch-up sexually.”

By the fall of 1980, Strub had been treated for STDs, hepatitis B and “a mysterious swelling” of his lymph nodes. Quiet, urgent reports of the death of “a handful of gay men” began surfacing months later and that scared him, but he was told that his immune system was strong, that he probably wasn’t sick.

Some time later, however, after contracting shingles, Strub was tested. The man he’d fallen in love with, Michael, was “matter-of-fact” when the results came back positive, but the diagnosis of “AIDS-related complex” was the catalyst for Strub to settle “into my first extended period of monogamy, or close to it.”

But at that point, for Michael, it was too late.

As memoirs go, this is definitely a different kind of animal.

Though it begins with Washington goings-on and inner-circle politics (and it visits that circle often), Body Counts ultimately becomes more of a coming-of-age coming-out that will resonate with gay men who remember the post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS years. That’s wrapped in tales of the infancy of LGBT activism.

What will keep readers rapt, though, are the horrifying jewels of this book: the author’s howl-of-grief memories of the early days of the AIDS epidemic; of dying friends; of visiting a hospital — not to see anyone specifically, but because he knew there’d be someone there he’d know.

Strub leaves such images that stick with the reader for a long time. For sure, those stories make Body Counts worth a look.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra