In Patricia Highsmith’s classic 1955 suspense novel The Talented Mr Ripley, she introduced readers to a young man who’s brilliant, lonely, possibly gay and desperate to reinvent himself . . . by any means necessary. The queasy genius of Highsmith’s book is that Ripley becomes a monster, yet she makes us understand him, even sympathize with him, every step of his murderous way.

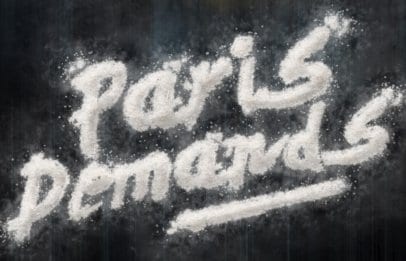

In Mike Miksche’s first novel, Paris Demands, Roger is a young man — not nearly as sinister as Ripley — possessed with the same drive for reinvention. He’s eager to live life on his own terms, and has just the right amount of ruthlessness to get there. From the opening chapters, as Roger awkwardly navigates his new life in the City of Lights and his conflicted feelings toward his still-yearning ex and his new, coke-dealing French boyfriend, Paris demands Roger’s innocence, if not soul.

“I did live in Paris for a year, which is where I wrote the novel,” Miksche says. “Paris was the perfect city for such a story, because she’s usually portrayed as the city of love, but in actuality she’s just a big ol’ dirt bag of a city that’s cold and impersonal (like any other of that size). This illusion of the city becomes a great metaphor for the illusion that Roger has of how love should be. He wants it to be perfect but it never is, which is the root of his angst. It is a love/hate relationship that he has with the city, but those really are the best type of relationship,” he says with a laugh.

“I knew I was becoming something else, something evil,” Roger muses during a coke-fueled party early on, “but that’s because of Paris.” Miksche perfectly captures the vaguely paranoid feeling of partying with unknown people in a new place before the reader slowly begins to feel less afraid of what harm could come to Roger and more afraid of what harm he could do, to himself or others. But can that really be blamed on this particular city?

“I do think any big city can do that to someone, especially when they’re alone at such a young age,” Miksche says, but notes that “Paris is a very demanding city. It’s not an easy city to live in because it’s so expensive and because it’s big and impersonal. There’s also the pressure to dress well (being a fashion capital), to love well and to eat well — but when you’re barely scraping by, like Roger, it can add a lot of pressure to your life.”

Nor can he afford the copious amount of cocaine he’s doing (enough to form the title of the book on its cover!) which happens to coincide with his emotional spiral. Is Paris Demands a cautionary tale?

“Personally, I’m not a fan of chemical drugs for myself,” he says. “I don’t judge people that use them and I’m grateful for some of the experiences I’ve had on them, but I have an extremely addictive personality — I had a bit of a drug problem, so I tend to stay away. There’s a duality to drugs. If you feel good, and if done in moderation, they can be a lot of fun. If you feel bad, and use them excessively, they can be destructive. Roger wasn’t feeling good so the drugs didn’t help. I wouldn’t say I’m anti-drug though. I do love my 420!”

In Miksche’s columns, he celebrates the glorious potential of BDSM and public sex to connect people — but in this novel, Roger begins actively using sex as a way to distance himself from people in a zero-sum game of hurt-or-be-hurt. He becomes the most dangerous thing there is: a man who thinks he knows what he wants but doesn’t.

But power corrupts as Roger navigates a winding series of romantic and sexual encounters. Will he return to his clean-cut boyfriend Pete, or stay with sexy drug-addict Marcel, or end up with someone altogether stranger, like Henry? And what will be left of him by then? All we know for sure is that the real power in Paris rests with its endless supply of supercilious waiters. Can they all be as snotty as the author portrays?

“Yes, all Parisian waiters are jerks!” Miksche jokes. “Okay, maybe not all, but most!”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra