In February 2021, the first winter of quarantine, Chloe Sherman’s sumptuous photographs from the 1990s–early-aughts queer/dyke underground scene in San Francisco burst across the Instagram timeline. Through the tiny portal of my phone, a non-place outside of time I’d been frequenting more than ever to escape the non-time of being fixed in place, the photos transported me back to a time and place that had been the prodigious inverse of COVID-time, when every day and night the opportunity to gather with, strut for, feast eyes on and make art with other young queers offered me what felt like a delirium of community, company and creativity.

Sherman’s daughter had spotted a ’90s-era photo by her mother floating around unattributed on social media. Sherman’s photographs were published in print books some 25 years prior, such as Nothing But the Girl: The Blatant Lesbian Image, edited by Susie Bright and Jill Posener—you’d be lucky to score a copy of this out-of-print text for under US $200 now. Sherman’s daughter stepped into the role of ad hoc social media manager so that the work could be properly attributed. She convinced Sherman to share her extensive archive of photographs on Instagram.

“Corner Store 14th & Guerrero St.,” 1996. Credit: Chloe Sherman

In the strange dissonance of isolation, Sherman’s photographs of that community—our community—became colourful dopamine hits to look forward to. Sometimes we DMed back and forth about names that might have changed over time, and those brief communiques formed a sweet lifeline of connection to an old friend and deep reminiscences of people in that scene I’d looked up to, admired, learned from, emulated or crushed on.

I moved to San Francisco in 1993, as far across the country from my hometown as I could get. Zöe Lewis, musician and a longtime queer cultural fixture of Provincetown had instructed me to go to Red Dora’s Bearded Lady café upon arrival, find the owners, Silas Howard and Harry Dodge, to whom she had sent me. I soon barnacled myself into the space and found housing from the café’s loose-leaf binder, made friends, was invited to show art and to perform in one of the many shows after-hours in the tiny space. An ever-present thrum of sex beat inside those days; the sauce of our creativity, inviting us to a revolution we could dance—and fuck—to. To be openly queer, gender-creative and alive, to make friends, art and music, and to fuck, and hang out and to be beautiful and handsome for each other in the ’90s was no small thing in a world that wanted us dead. Sherman’s photographs brought a rush of memories captured in rich, saturated colours and grainy black-and-white textures—queer femmes in sleek slip-dresses, butches and future trans guys performing a multiplicity of masculinities in vintage suits bought for a few dollars at a thrift store, and oh, those gas-guzzling classic cars and motorcycles! Rent and gas were cheap, and places like the Bearded were our home base. Sherman was at the nucleus of it all, a documentarian from within. In 1994, Sherman and I had an art show at the café titled New Blood—her colour-saturated photos and my paintings and block prints.

“The Desk,” 1996. Credit: Chloe Sherman

I’ve written elsewhere about the formative impact on me of queer ’90s SF and the long-reaching creative influence that germinated in that time—but part of me has wondered over the past quarter-century if my memories of the unreal beauty, sex-forward creativity and larger-than-life femmes and butches had grown hyperbolic. But now, Sherman’s photographs of this scene of friends and collaborators, lovers and rivals, bandmates and coworkers—all of whom participated in a subcultural world inside of, often invisible to and certainly never beholden to, the larger mainstream world—proved my memories accurate.

“Anna Joy Post Surgery at Home,” 1997. Credit: Chloe Sherman

A sense of queer thriving, joy, creativity, sexuality, camp and colourful bravado undulated from every post Chloe made. Those of us who were there understand the backdrop, the precise brutality of those years, which offsets what author, punk femme singer and scholar Anna Joy Springer calls, in the introduction to Renegades, “our subculture’s DIY performative ‘fake-it-till-you-make it’ approach to collaborative self-creation.” Through the laborious process of reopening years of archived negatives, scanning new prints and posting the images, her art not only spoke to those of us who were there, it also reached a new, broader audience of younger queer and trans people, print photography fans and art lovers.

“Stormy in Van,” 1998. Credit: Chloe Sherman

Folks clamoured in Instagram comments that this body of work deserved to exist on our coffee tables and in our greedy hands as a print book. Sherman was ahead of us—she had such plans already in the works, along with gallery exhibits in San Francisco and Berlin, where large-format prints of her images could be viewed up close in person. With vaccine uptake on the rise, acceptance of masking in public growing and hospitalizations falling, art openings—one of the things I most missed during the pandemic—were becoming cautiously possible again. I’ve never attended a high school reunion and never will, but when Sherman’s exhibition of this work was announced, I knew that I had to travel back to the Bay from my current home in Halifax, Nova Scotia. I needed to be with my peers who’d survived the past three decades and its crises, including AIDS, racism, addiction, overdoses, suicides, mental health crises, homophobia and transphobia, late-stage capitalism and a loss of affordable, stable housing—and queer gathering spaces—to tech gentrification and speculative real estate, only to find ourselves on the other side in the strange ontology of middle age.

Now Sherman’s photographs are available to explore in quiet, analogue communion in her sumptuous new book, Renegades: San Francisco, The 1990s. The collection-as-book seems so fitting, as photography books of that period, such as Body Alchemy by (Rex) Loren Cameron, and The Ballad of Sexual Dependency by Nan Goldin were portals to queer/trans visibility in which I’d been able to find recognition and legibility turned into art. I needed to see images of people like us, like me, seen through an admiring and conspiratorial eye, because the culture held no mirrors for us, especially butches. I have somatic memories of hanging out alone or with a friend, getting buzzed or stoned or both, and poring over the pages of these books, taking in the details and divining stories from the textures and colours and compositions of the shots. It was a different time: finding images of a queer life that echoed your own was a labour of love, and largely required seeking out print zines, small-press books and independent magazines. In much of the U.S., finding these printed images meant hunting down a physical bookstore that would sell them—another feat.

“Crystal and Marci,” 1995. Credit: Chloe Sherman

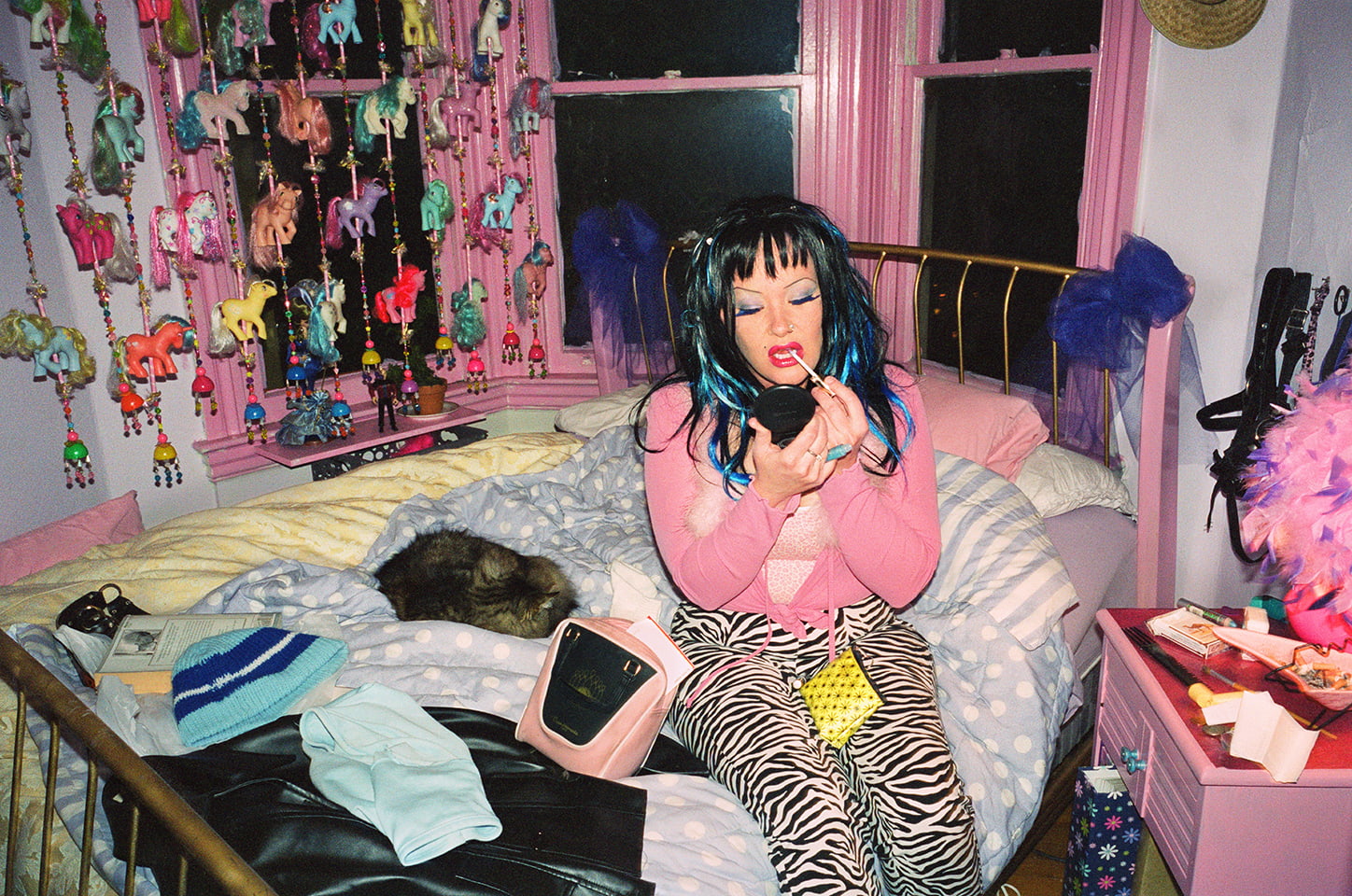

The photos collected in Renegades allow for such moments of seeing, inviting the viewer to step closer and linger, to bask in the glamour of thrifted excess and the maximalist bricolage of the spaces we made home. From peacocking handsome butches and proto-transmen in embroidered western shirts, tuxedo ruffles and polyester pants, to the delicious pastiche luxury of lush femme bedrooms and the queer women who inhabited them, there is intimacy—Sherman captures that which was freely given.

“Ulla’s Room,” 1998. Credit: Chloe Sherman

“Miss Deena,” 1999. Credit: Chloe Sherman

I remember Sherman always toting her heavy 35mm camera around, but have fewer memories of her actually shooting the pictures. There’s one black-and-white photo of a group of us getting coffee at the Bearded Lady café before walking down to the Folsom Street Fair. It looks too bright and too early in the day for so much leather and so few clothes. But we all half turn with easy glances and soft smiles when Sherman hails us. The ease of her looking comes through in the picture: we want to be seen as she can see us. We are dressed up and strutting for each other, wanting to conjure a gaze of desire to undo the looks of derision or hatred we feel outside the bounds of this world we made for ourselves and each other. Sherman was always ready to capture us all, her friends, looking like the rock stars we wanted to be.

The advent of the smartphone has rendered constant camera-carry and instant image production a quotidian norm, perhaps, but when Sherman first shot these images on film, an intentionality and care was required by the material constraints of her craft. Film photography was—and is—expensive. Film photography requires skill, vision and good timing. Her presence was that of an insider and friend, and her observations were unobtrusive.

“Elegant Dining,” 1997. Credit: Chloe Sherman

Sherman was as much a part of the queer beauty and expansive, inclusive creativity of her community as those she photographed. Renegades captures this trust and connection. Perhaps it is this sense of intimacy, of photographing one’s own friends and community, that is the essence I hungrily absorbed from those books I loved daydreaming over. There is no other in Sherman’s work, only an us, a we.

“Summer in the City,” mid-’90s. Credit: Chloe Sherman

Nostalgia gets a bad rap, in particular when it becomes an indulgence to evade the present, or is used to glaze over negative aspects of the past. But there are also plenty of positive aspects to nostalgia, like when we can integrate the positive emotions we gain from reminiscing about the past alongside our present-day realities.

Maybe it is another thing altogether to look back at a moment of a past you shared in some small way to find it has been recontextualized as history. The distance of time can help us understand how a multiplicity of forces situated a time and place. We might see how things that seemed impossible to surmount in the past might have fortified us for the challenges of our present moment and imminent future, or how a few friends can make a place with their bare hands that incubates a community and creates a home base for us, and that we don’t have to accept the premise of the broader culture’s questions for our existence. The time and place documented in Renegades reminds us that desire and play can be a potent organizing principle for making queer and trans life livable.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra