Patricia (far right) with the staff of Buddies, in 1994, as they prepare to move into their current home on Alexander Street. Credit: Tony Fong

Patricia with her partner of 22 years, Helene Ducharme. Credit: Tony Fong

Pink Triangle Press creative director Lucinda Wallace and Patricia compare cheekbones in a ’90s Xposed column. Credit: John Simone

Credit: John Simone

Credit: John Simone

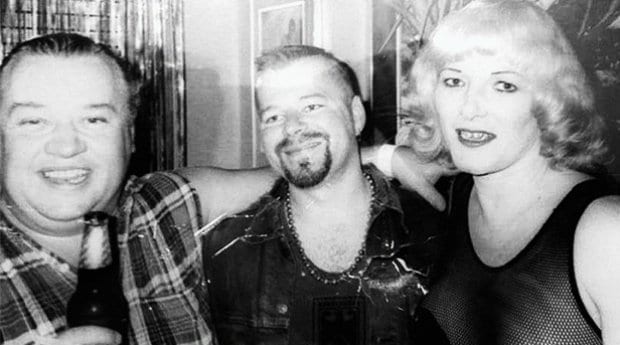

David Ramsden, Tim Jones and Patricia. Credit: John Simone

Credit: John Simone

As Patricia Wilson hands me a drink, I pause to take in the space around us. An otherwise straightforward one-bedroom in the heart of the Church-Wellesley Village, Wilson’s apartment is designed with an eye to the nurturing but tough-as-nails persona for which she is famous.

“Be careful. I make them stronger than at the bar,” she warns.

Towering piles of art books, Marshall amplifiers and other hard-rock artifacts sit alongside rubberized dog toys and a blossoming summer patio where Wilson and her partner enjoy their meals. The juxtaposition between these elements could be jarring, but here it all makes perfect sense. Reclining in an Adirondack chair, she stops midway through a particularly salty tale to call attention to a falcon on the horizon. This is her personal oasis, cobbled together from the disparate influences that make her whole.

Whether serving up drinks to partygoers as bar manager at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre or as the lead guitarist in her band, Crackpuppy, Wilson has been a visible presence in Toronto’s LGBT community for well over two decades. Her unapologetic, no-nonsense attitude makes her an easy punk role model, with a middle finger aimed firmly at authority and with any number of stories about alcohol-fuelled benders in many of the city’s most famous rock clubs.

Still, beneath the tough exterior lies a benevolence that is incredibly disarming. A self-described spiritual person, she refers to the young Buddies patrons as her “queer kids” and spends a good portion of our time together petting her black Labrador retriever and making jokes about her 60th birthday.

“I never thought I’d make fucking 60,” she explains. “Seriously, I don’t know what I’m going to do. I’ll be behind the fucking bar at Buddies with an oxygen tank and a fucking walker, ’cause there ain’t no way I get to retire.”

The birthday milestone has given Wilson a chance to reflect on her life. And as she opens up about her journey, it is clear that both spiritual and musical components have always been at play — even if their origins are somewhat surprising. She takes a certain pleasure in revealing that growing up in Windsor, she and her siblings were encouraged to study classical piano at the nearby Ursuline School of Music, a Roman Catholic conservatory.

“All the kids in the family took piano lessons. I think I started playing in Grade 2. You’d go to the convent and play with the nuns. It’s true! Some of us went further — my sister’s a very good visual artist. But she still loves her piano.”

The time at the conservatory had a huge impact on Wilson’s development as both an individual and a musician. Still, she isn’t shy in noting the important influence of Beat Generation writers like Allen Ginsberg, William S Burroughs, and Jack Kerouac. In fact, it was in the aftermath of the Beats — and during the burgeoning counterculture of the late 1960s — that Wilson first began experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs. She considers the experience to be revelatory and quit school at 16 to move into what she describes as a “hippie-rock place.”

She remembers getting to a point where she was doing LSD daily.

“[LSD] is the best drug I’ve ever done in my life. It changed my life. It made me realize how much more we are as human beings … Mind you, I was done [with it] by the time I was 19 because it kept giving me the same message. But it made me realize what was important to me.”

While the message had a lot to do with Wilson’s evolution as a musician, a central part of it was also an awareness of her identity — something that she had struggled with throughout her young life. And although she acknowledges that gender was inextricably linked to that personal journey, she is hesitant to make her experience be entirely about her transition or transsexuality.

“I mean, maybe I’m just a tranny redneck. Maybe I don’t like new things. I don’t know. But I’m exactly who I am now as when I was 16 years old. I was at the Clarke [Institute of Psychiatry] shortly after they opened [in 1966]. I had already known at that point that I was — I don’t think they called it ‘transsexual’ back then. They called it ‘fucking deviance.’ But I already knew I was a deviant.”

Wilson is careful not to minimize the importance of her surgery or the role that it played in saving her life two decades ago. Still, she wishes more emphasis would be placed on self-discovery and providing young trans people with the opportunity to understand themselves fully before submitting to the pressures and expectations of mainstream culture.

“I think it’s important to be who you are, and learn who you are first. If you don’t, then you have to go through the fact that you’re fighting two monsters,” she says. “You’re fighting the monster of self-awareness and the monster of trans at the same time, and that means both of them are going to suffer.”

After years of shuffling between Windsor and Detroit in the early 1970s, Wilson finally took the famed Route 66 across the United States in 1976, travelling with a group of musicians she jokingly refers to as “very, very bad people with no morals at all.” Settling in Los Angeles, she became firmly entrenched in the rock music scene before eventually moving back to Windsor to become an arts administrator in the early 1990s.

It was then that Buddies changed her life. Hired directly from Windsor, Wilson joined the theatre company as a publicist at the George Street location. She felt an immediate investment in the organization’s mandate.

“Buddies is very important to me because it’s about the kids and the art. I’ve always felt really strongly that we get to save lives because there are so many kids that don’t get to have a queer experience. They get beat up at the breakfast table over their Wheaties because they’re too queer for their dads or their brothers. And I feel that we’re a refuge for them.”

And she feels a special kinship for queer youth who are targeted because of their differences.

“I always make sure that the kids I know who can’t walk down the street without getting second looks or getting bashed — those are the ones that I take care of. My queer kids. That what I call them. My fucking queer kids.”

So what’s next? Wilson is currently performing and recording new material with Crackpuppy. The band, which Wilson co-founded with Drew Rowsome back in 2003, has a new lineup of musicians and a different sound. And after two successful performances at WorldPride (including one in Yonge-Dundas Square alongside The Cliks and Against Me!), the band will be playing the Spread Eagle event at the Black Eagle later this month.

“We now have [guitar player] Mark Crossley, [drummer] Cathy Marchese, Drew and myself. So the sound is completely different. I would say we’re closer to punk than we were before. More metal; maybe compare it to Ozzy Osbourne. That kind of thing.”

As she leans back in her Adirondack and stares out over the horizon, I ask if she has any thoughts on the significance of her upcoming birthday.

“I mean the fact that I’m playing music with the band that I’m in now and jumping around … I’m thankful, but age doesn’t really matter. It really doesn’t.”

She pauses.

“I mean, I suppose the good thing about being 60 is that if I ever wanted to take the subway I can get a discount because I’m old. That’s a good thing, I guess.”

Crackpuppy plays Spread Eagle Sun, July 20, 8pm. The Black Eagle, 457 Church St. crackpuppy.net

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra