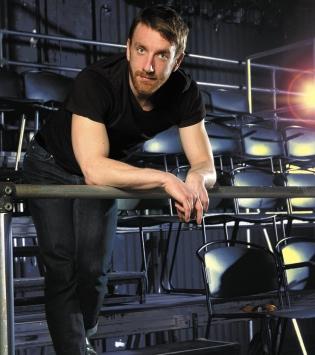

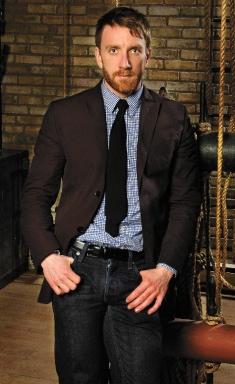

Credit: David Hawe photo

He’s the man who was once a gender-ambiguous little boy with fingernails painted blue (applied by his openly bisexual dad), a little boy who loved to play with dolls and dollhouses, who made those dolls part of an “insanely rich and detailed dynasty,” a little boy in a rough part of town who got beat up a lot, whose hippie parents split before he was born, who spent a lot of time alone, who had a rich imaginary life, who grew up bilingual in Montreal. That may not have added up to a “lovely, pastoral childhood,” as he puts it, but it does read like the perfect background for a career in the arts.

Today, Brendan Healy is the artistic director of Toronto’s Buddies in Bad Times Theatre. He’s only the fourth to hold that position in the company’s 31-year history, and he’s the youngest. That’s a description that makes him just a little uncharacteristically grumpy. “I’m fucking 34,” he says. “I’m not young. I know what I’m doing; I have life experience. I’m not some kid.” He’s no longer gender-ambiguous either, with his mildly caffeinated masculinity, his crisply ironed shirts and his conservative ties. Don’t let those externals fool you, though. He’s as queer as they come.

I’m in the main space at Buddies, watching him rehearse Breakfast, which opened March 19. It’s a remounting of a collectively devised show that scored three Dora nominations when it played at the Theatre Centre two years ago. He directed it then and is tackling it again with the same cast, though he says they have collaborated to produce a new and stronger ending. There are some 11 people milling around, but there are only three actors, all women (the others are techies — it’s a tech-heavy show). The comfort level among them, and with him, is very high. There is much light-hearted banter about the repeated request “to set a sound level for the orgasm,” which sends one actor into several extended — and convincing — sighs-and-moans arias.

He’s not a director with a reputation for tantrums or incivility. If Healy wants some adjustment on the set or lighting, he’s likely to phrase the request as, “I don’t know how you’d feel about…” Performer Nina Arsenault, whom he directed in The Silicone Diaries, describes his technique as “generous, empathetic, supportive and smart. If we ever had disagreements, I had so much trust in him that we could just talk it out. It was so clear that he is committed to his love of performance with all of his being.” Daniel Brooks, artistic director at Necessary Angel, met Healy when the latter was a student at the National Theatre School in Montreal and remembers him as a “bit of a control freak who can get very emotional if he feels things are slipping out of his control, but directors are often like that. He is also an incredibly sensitive and personable artist with an attraction to the real human process that theatre is. He gets very alive, human performances from his actors — and dictators don’t get that.”

Performance helped lift him out of the gawkiness and insecurities of his childhood. In his early teen years, he got involved with an inner-city youth project in Montreal. The city had turned over an abandoned hangar to a bunch of kids and encouraged them to create, direct and perform new plays, and it was there, he says, “that I came into my own. I’d been lonely and isolated, and this gave me a way to connect with others. I came out, got laid, got drunk and started smoking.” (He has yet to quit, and periodically takes a cigarette break during rehearsal.) He had his first sexual experience at 14, with a girl. He has had other sexual experiences with women and says his greatest love (of the non-sexual variety) was a woman, who came out at the same time he did, was his muse, and is currently “a very lean, very muscular, very queer performance artist who lives in Los Angeles.” Still, he prefers men, sexually and romantically, and loves “the companionship of men. I like being around men. I like their masculine energy.” (He is currently in a long-term relationship with Gregory Prest, an actor with Soulpepper). He’s queer enough not to shut any doors, and though he’s never had sex with a trans person, he enjoyed the almost stereotypical male/female dynamics that informed his collaboration with Nina Arsenault.

“For the first time in a long time,” he says, “I allowed myself to feel really attracted to a woman. I like feminine women, and she really embodies that — lighting her cigarette and opening doors for her, those man/woman rituals. She’s very good at making you feel like a man. I can get into those gender roles. They’re fun, and playful. I don’t war against them.”

Though he studied directing at the National Theatre School, he began his career as an actor, most memorably playing the kind of queer little boy he once was in a drama called Girls! Girls! Girls! He describes himself as an actor of limited range, but he found that role particularly challenging.

“They wanted me to be really faggy. I’d straightened myself out when I was 12 or 13, become kind of uber-masculine and athletic. I got a kick out of people thinking I was straight. Suddenly, I had to deal with my own internalized homophobia, and that was hard for me.” It did help him realize, though, that he was a much better director than he was an actor, an awareness fortified by his experience interning in Manhattan under the legendary Richard Maxwell, of the New York City Players.

“He had a huge impact on me,” Healy says, “through the uniqueness of his voice and the purity of his pursuit as an artist. It was really inspiring. He’s an auteur, and I gravitate towards auteurs, people who are on some kind of investigation larger than the work. I like to think that what motivates me as a creator is more than just getting the show up, that I’m asking questions about existence, about life, about theatre and performance, about what theatre means, about why it’s important to society.”

Asking those sorts of questions in a queer context is part of his mandate at Buddies, where queer is defined as considerably more than gay, lesbian, bi and trans. According to the company’s official mandate, it includes “work that is different, outside the mainstream, challenging in both content and form.” Healy, who cites influences ranging from Foucault (“his History of Sexuality rocked my world”) to Derek Jarman and Jean Genet, has an articulate take on what he calls the three fundamental queer values: a true celebration of difference, a rejection of assimilationism, and a rejection of essentialism.

“We say people are different from one another, and that’s okay and it’s important. It keeps society rich and open and dynamic. We reject assimilation — being accepted doesn’t mean fitting into the status quo. It’s the status quo that should adapt itself to difference. We reject essentialism because, though queers celebrate difference, it doesn’t mean that we can’t get along. Maybe your difference will rub off on me, and make me a little more different, like you.”

If that all sounds crazy hopeful and pie in the sky, that’s because Healy also believes queers are utopian.

“We believe,” he says, “that one day homophobia, sexism and racism will disappear. That the queer liberation movement is also about liberating straight people. Queers are happy, self-actualized individuals, and we look at straight society and we see really contrived relationships and pre-determined modes of behaviour. We’re all about liberating you. We’re all queers. It’s just that some of us are more open.”

That’s unashamedly 1970s-era gay lib talk, and it’s good to hear it from someone who wasn’t even born then. He’ll need that passion and all his smarts, energies and enthusiasms to cope with the challenges facing theatre in general and queer theatre in particular. Buddies has experienced bad times of late. Audiences get smaller. People are busier. There are more forms of entertainment than ever. Healy is pleased that Buddies has the youngest audience base in the city, but that won’t mean dumbing down, or less risk-taking. He wants to work with young creators who are interested in a collectivist approach (as unfashionable as that might be in an ego-fixated, celebrity obsessed world). He wants to produce content-driven work. “I want meaning,” he says. “We have to go back to ideas.”

A tall order. It’s good to know it’s in the hands of a one-time more or less fucked-up little kid with blue fingernails and a crazy fantasy life, a kid who grew up but never quite lost that queer edge. Just right for Buddies in Bad Times.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra