In Tell Me I’m Worthless—released in January this year by trans author Alison Rumfitt, a haunted house with a fascist political ideology terrorizes the story’s protagonists, Ila and Alice. The duo, who live in a grim English city, alternate between being friends, lovers and not speaking to one another. Ila, speaking about the house, and speaking about the U.K., says, “I don’t know what I believe, I just know I want to be free of it, truly. I just want to pull it out from under me, look at it beating in my hand and then crush it.”

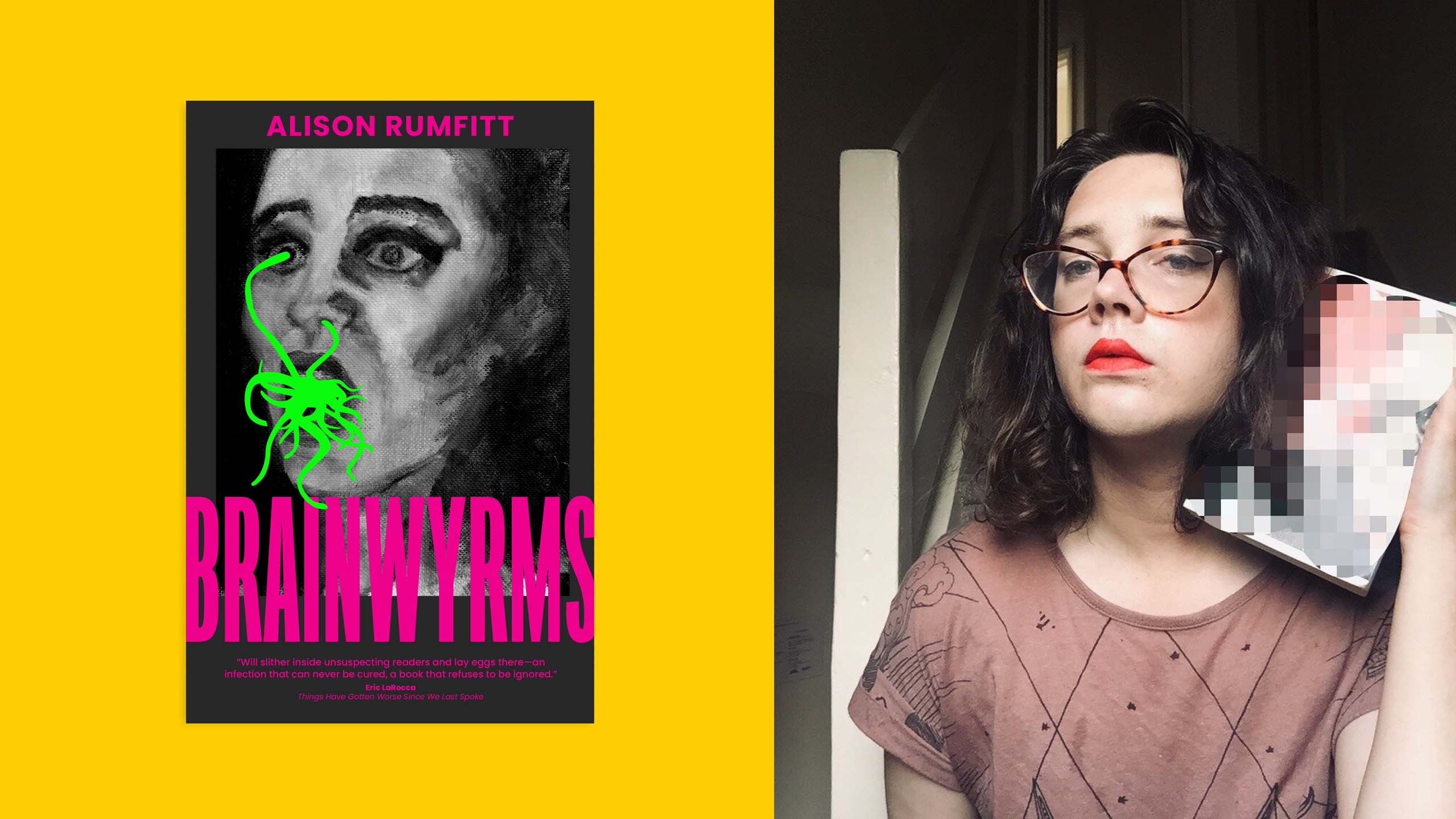

In Brainwyrms, Rumfitt’s second novel, out this month from Cipher Press and Nightfire, the main character, Frankie, also wants out, wants it over with, is sick of Britain. Life is exhausting in the worlds built by Rumfitt, in which the threats of violence are both structural and close. There is a visceral darkness in her novels, an eeriness that reminds me of the attic spaces painted by Michelle Uckotter. Creepy, yes, but familiar as well.

Both novels are set in contemporary Britain. Here, access to trans healthcare is limited. Trans people can wait up to seven years for an initial assessment from the NHS’ Gender Identity Clinic (GIC)—which is the ordinary route to access publicly funded hormones and gender-affirming surgery for trans people. And trans rights have become a political issue on which both major political parties have demonstrated that they are not on the side of trans people. The Conservative government has recently announced that it will ban trans people from access to male- and female-only wards in hospitals and it is expected that it will announce guidelines to require, in circumstances where a student is questioning their gender expression, that the school tell that student’s guardians about it and ban the student from transitioning if their guardians do not approve. The Labour Party—Britain’s more “progressive” party—has failed to oppose the proposals and last year, party leader Keir Starmer, suggested support for these changes, emphasizing the importance of “safe spaces” and that children shouldn’t be making decisions on these issues without the consent of their parents.

Where Tell Me I’m Worthless is a haunted house story, Brainwyrms is a body horror. Frankie, a trans woman, is at work at a GIC when a transphobic woman bombs it. Frankie lives, her co-worker Tabi dies (“… the lucky bitch. Cis girls are always spared the worst of the pain”). But the psychic impact of the attack stays with Frankie. She now works moderating content on social media, witnessing all manners of horror through her screen (“rape threats, … a video of a beheading or the cartel killing of a woman or leaked photographs of a celebrity suicide”). At a club one night, Frankie is granted a bit of distraction when she meets Vanya (“Petit little Polish elf. Baby. Daddy. Puppy. Good girl, good boy. Short king.”) They ask Frankie, “So, I don’t want to be too forward, but I might as well ask, given where we are. What is it that gets you off?”

What follows is romance. They go on a walk to the countryside and Frankie removes a tick from their leg. She goes to Vanya’s home for their birthday. Frankie, though, remains unsettled by Vanya, whom she thinks is hiding something. As Frankie looks closer, Vanya’s story—and the book’s—becomes larger, more unsettling, gross, terrible.

When I spoke to Rumfitt over Zoom this month, she was dealing with an allergic reaction to carpet beetles in her new flat in London. Life, for her too, is exhausting.

Despite her discomfort, Rumfitt offered direct and thoughtful meditations on her new novel, transphobia in the U.K., anonymity in social media and writing horror.

At the end of Tell Me I’m Worthless, there is a sense of optimism. Reading your second book feels different though. The epigraph to Part One is a quote from Suspiria by Luca Guadagnino, which includes this question: “Why is everyone so ready to think the worst is over?” Is it accurate to say that in Brainwyrms there’s less hope for change within the U.K.?

Yeah, I mean it’s partly a genre change and partly maybe a change in my [outlook]. Tell Me I’m Worthless is a fairly optimistic story about two people violently deradicalizing themselves. The end result is that, yes, these are both toxic people, but the fact that they care about each other does mean something—it brings them forward into a better version of reality, or at least a better version for them. And Brainwyrms is another book about two people in a dysfunctional relationship, but it’s not about seeking redemption in the same way.

It has different goals in mind. Tell Me I’m Worthless obviously was extreme, but it is a haunted house story. Generally, haunted house stories have this particular arc to them and I did follow that arc generally.

Do you mean to say a redemption arc?

Yeah, or at least the characters coming into self actualization. Like, The Haunting of Hill House doesn’t have a happy ending, but it has some sort of actualization to it. Brainwyrms is in a different genre space. And I maybe have a different mindset now than when I wrote Tell Me I’m Worthless. I’m probably a little more fatalistic a little more, I don’t know, acerbic.

What underpins that bitterness?

Changes in my political outlook. In general, I have less hope for the world than I did. I think that’s probably the main thing. Tell Me I’m Worthless has TERF characters, which the book at least tries to analyze. But Brainwyrms has some TERF characters and they are cartoon villains who do the most ridiculous, over-the-top things.

Do you see those two aspects interlinking? It sounds like you are both bitter about contemporary U.K. life—and find the TERF-yness of it comedic?

Yes, definitely. I do obviously find it scary, but I find it laughable now. Not that I think transphobia is not to be taken seriously, but, I don’t know, it’s so ridiculous and stupid and bleak.

I feel exactly the same. For readers outside of the U.K., would you be able to unpack some of the contemporary issues facing trans people in the U.K.?

It does feel particularly bleak because there isn’t even this notion of liberal protection going on in the way there maybe is in America. [The government] just tried to ban trans women from female-only wards in hospitals, which are barely even a thing. The policy isn’t actionable. Fundamentally, it doesn’t mean anything beyond the fact that they did it and it is a clear statement of intent. Imagine if loads of right-wing people were like, “Oh we hate you. We believe you’re a rapist. We don’t believe you’re a woman, etc., etc., etc.” I guess there is this a bit in America. There have also been New York Times liberals being anti-trans, but it does feel like they have less of an institutional power than the Labour Party here being anti-trans.

It’s not that I’m pro Joe Biden, but he at least has said that trans women are women and I don’t know if he actually believes that or if he has been fed the lines by his handlers, but it’s something. [The Labour Party] is like, “Well, the Tory Party has said that they want to put trans women into a big car crusher. We have to listen to their ideas. It is what the people want.”

Both of your books grapple with the structural and the small manifestations of transphobia. In Brainwyrms, Vanya’s mother has this horrible, parodic transphobicness to her. How does structural transphobia influence more interpersonal instances of transphobia?

[Vanya’s mother] served a really good plot purpose, but also I did want to show the personal impact of these ideas taken to their most extreme. That was my thinking there. It is important to show these personal impacts and how they tear people apart.

One way of reading Brainwyrms is that it is a book about disappointment in those close to you. And that is the overarching horror. That even those dear to you are monsters. Why did you want that as a theme of the book?

I don’t even necessarily believe that is true about people—but it is a good hook for trying to scare readers. Like, making people think about how much they can trust people. It’s a very scary world sometimes and I’m exploring personal stuff in my writing, but I’m also writing work that is primarily meant to entertain and shock and make you scared. And the thing that I find scary is that we can never possibly know the fullest extent of someone, and someone can’t know you properly.

Brainwyrms is generally written in the third person, but switches, at times, to a direct intervention from an unnamed narrator who talks about what gay life used to be like. The narrator says, “The cops, after that, started to raid the gay bars. But every time they tried, the gays inside would do the same. Cease individuality just for the time they needed to. Limbs interlocking until the skin was pressed close enough together that it became the same skin…. This is what we have lost.” How do you think we get back to a time when queerness is more of a collective struggle and what is stopping us from being like that now?

I’m not sure. I think we got too comfortable, maybe, in our supposed liberation. I don’t know where the route back would be. I guess that’s why I write fiction and I’m not a community organizer. But with that specifically, I was just thinking about stories I’ve heard from older queer people, about queer life, especially in Brighton, and responses to gay bashings from fascists who would specifically seek out gay bars and smash windows and stuff. And so I was just, like, that intensity of response to fascism doesn’t feel even remotely like a possibility, if there were to be an attack now.

Because there isn’t the same community sense to gay life?

Yeah—all of the community spaces have been destroyed. They’ve all been sold off or turned into random shops. There’s not a gay quarter anymore.

In Brainwyrms, you write: “you didn’t want a body you wanted to cum.” And: “Fucking isn’t enough anymore. I need you to kill me.” It reminded me of McKenzie Wark’s Reverse Cowgirl, and her own particular vision of desire and her transness, seeking a kind of nothingness in being fucked to obsolescence. I’m interested in you expanding on that quality of desire. What does that look like to you?

It’s not how I feel, but it is a trend of a way of talking about sex that I’ve noticed from people. And it might be that because the trend is sort of easily shareable online or particularly shocking, I don’t know, but it is certainly a trend.

Do you mean in the way people on Twitter would be like, “I need Paul Mescal to step on my throat” or whatever?

Yeah. The characters that I write about are aware of contemporary culture so they do talk in a way that reflects these trends. There’s a desire for obliteration that people have, but generally it’s not like they actually want that, which is kind of what the book is about. It’s about saying you want something, thinking you want something, and then the actuality of having that and whether it feels good enough to be worth the pain.

The world of the internet in Brainwyrms is focused on Reddit-style anonymous group chats on servers rather than Instagram or other public-facing social media. Why did you choose those forums as a setting for your novel?

I find people are generally more honest when they’re anonymous or semi-anonymous. And those anonymous things do have a way of intruding. Anonymous posting and conversation hasn’t gone away. I think we may see a return to forums and anonymous group chats as people crave different experiences online that are maybe more focused on specific communities. I didn’t necessarily know that when I was writing Brainwyrms, but I think I may have tapped into something, into a trend.

Why do you think people want more anonymous spaces?

Because they are scared of observation. People keep trying to say things anonymously even on their public-facing social media—like the trends of close friends on Instagram and circles on Twitter. Those people like to be able to post something that a certain group of people can see. I enjoy it. I can be a bit bitchier on there.

In Brainwyrms, Frankie talks about herself as a clown. And there are other moments where she thinks about herself as ghoulish because she doesn’t meet the standard of femininity or womanhood.

The clown thing is a trend in how right-wing people talk about trans people. They have this recurring thing of the clown world—in their minds, the world is populated by clowns and they are the only non-clowns. So it was a way of showing that Frankie has herself been starting to view herself the way right-wingers might view her because she’s spent enough time looking at this stuff. So she sort of became the boogeyman in a way.

In the book, self-loathing is generally portrayed as an internalization of other peoples’ perceptions. As someone who has developed insecurities based on offhand remarks from others, I can relate to the idea that listening to right-wing commenters could destroy one’s self-image.

I’ve definitely viewed myself in the same way in the past. I guess I was just trying to be realistic about the relationships trans people might have to themselves, which, you know, doesn’t feel great sometimes.

Who is this book for?

Primarily, I intend for other trans people to read it. Obviously, both books seem to be doing quite well, and I presume they have a large cis audience, but I’m not really writing with them in mind. I’m glad they can relate to it or find entertainment in it.

The book explores how the growing tides of fascism and transphobia can exhaust you and prevent you from engaging with the sort of fulfilling valuable life that you otherwise might want to lead. Is that a horror in itself?

That’s the experience of just existing in the modern world and being overwhelmed with information constantly. Like, it is exhausting. There’s so much noise: both literal and figurative. A lot of my project in writing these books is in trying to write horror that feels particularly contemporary. It might not age super well, but I wanted to write work that feels of the now and that exhaustion is just something I see everywhere.

Have you managed to change anything in your life to help with that exhaustion?

Not really. There are things I enjoy and I try to make sure I sleep well, but if I’ve found a cure, I’d have written a self-help book.

You can put it in the next book maybe.

Yeah, what if the next book was just a self-help book? That would be great.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra