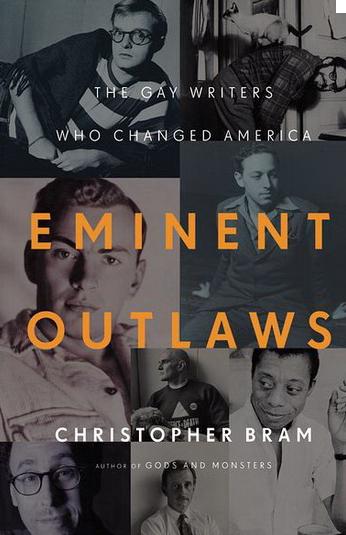

“The gay revolution began as a literary revolution.” The phrase serves as both opening line and thesis statement in New York author Christopher Bram’s new history Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America.

Bram begins with a small collection of gay male writers in the post-war period, then charts, with élan and insight, the emergence of gay literature in America, which reached a kind of apotheosis in the 1990s. He frames this historical survey as a theatrical narrative, its fascinating dramatis personæ making entrances and exits throughout.

The very fact that a book like Bram’s exists at all is a testament to the pioneering spirit of the movement’s early figureheads — luminaries like Gore Vidal, Truman Capote, Christopher Isherwood, Allen Ginsberg and James Baldwin. It is fascinating to reexamine the struggles of men who have attained a mythic status within the cultural landscape of contemporary America. Although in his introduction Bram expressly denies attempting to canonize any of his “outlaws,” his book is also proof-positive of the existence of a viable queer literary canon.

In that same introduction, Bram asserts, “I deliberately left myself out of this story. It would be impossible to talk about my own work without sounding self-serving.”

There is an obvious trap door in Bram’s apparent modesty. Any history of gay literature in the second half of the 20th century must surely include Christopher Bram — author of nine novels, Guggenheim Fellow and Bill Whitehead Lifetime Achievement award-winner. Luckily for his readers, Bram quickly (and repeatedly) inserts himself and his work into the narrative.

Though never offering a detailed account of his own literary impact, Bram does fulfill another of his introduction’s assertions not to “pretend to be objective.” He acts as an informed insider, a highly opinionated and occasionally (and delightfully) bitchy guide through six decades of queer cultural history.

Bram’s “large scale cultural narrative” begins in 1948 with the publication, in the same month, of Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar and Other Voices, Other Rooms by Vidal’s nemesis Truman Capote.

Vidal acts as a touchstone throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s, reoccurring through his friendship with Tennessee Williams, his ongoing feud with Capote, and his legendary propensity for managing to always be a witness to seismic political events.

Bram strikes a welcome balance between reportage — citing sales figures for gay novels and critical response as a barometer for the acceptance of gay-lit — and personal opinion. He never misses an opportunity to advocate for an overlooked work or artist, or to deflate what he views as an unwarranted reputation.

In the work’s second half, Edmund White picks up the baton from Vidal and carries it to the end of Bram’s historical relay. White is an appropriate choice, not only because his novel A Boy’s Own Story heralded a new phase in mainstream American success for gay authors, but also because of his HIV-positive status.

AIDS subsumes the narrative when Outlaws moves into the ‘80s, as well it must. The story of the early days of the AIDS crisis still has the ability to shatter, regardless of how many times one has heard it told, and here it is told movingly.

In a moment of sublimity, Bram reframes Wilfred Owen’s imperishable First World War poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” to comment on the horrors of AIDS: “If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood / Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, / Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud / Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues.”

Bram’s narrative of gay literary history includes discussions of such seminal works as Isherwood’s A Single Man, Tony Kushner’s Angels in America and Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, as well as Ginsberg’s Howl and the poetry of Thom Gunn and Melvin Dixon. Bram also provides a roll call of artists who achieved early success and were snuffed out by AIDS, representing a loss to gay American letters of unknown dimension.

Eminent Outlaws will likely be criticized by some for its reliance on famous quotes and well-known anecdotes. This is a misreading and a reduction. Much like Michael Bronski’s A Queer History of the United States, Bram’s work is a survey, which will no doubt serve as a gateway to further reading. Also — and it defies the journalists‘ imperative that states that one must always be on guard against such things — the fact that gay literature has advanced to a place where it is possible to have our own clichés is, in itself, a strange kind of victory.

As for the future of gay-lit, Bram is ambivalent. “We are going through a transitional period,” he says. “We don’t know yet what the next phase will be.” One hopes Christopher Bram will be there as a guide, wherever that next phase should lead.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra