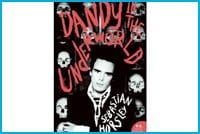

Sexual suspects don’t easily penetrate the clenched sphincter of US Customs. Professional bad boy Sebastian Horsley was denied entry recently for what the border cops called “moral turpitude,” citing his arrests in the UK for drug possession and prostitution. The incident got the queerish Brit dandy a feature article in the Sunday New York Times. Just who is this velveteened, top-hatted, ultra-indecorous almost-fag? You don’t know? Well, neither does he.

I was soon totting up the flood of aphorisms in this memoir and trying to recall who had said them already. “All art aspires towards the condition of music,” is a paraphrase of Walter Pater. “It is not necessary to have relatives in Hull to be unhappy,” is Groucho Marx shifted to Yorkshire. Oscar Wilde and Quentin Crisp make frequent pseudo-appearances. On the other hand, to say “self-destruction… is the quickest way to gain control over your own destiny” seems to be genuine Horsley.

Raised in a “soaring, rambling” manor house in the north of England, young Bash (a family nickname) made his mark early. At age five he crapped himself in school and was sent home “dripping with excrement.” The trauma didn’t deter him from peeking at the scatological William S Burroughs in his father’s library. A dialogue on butt-licking from Naked Lunch (“Aw shucks, now it ain’t dirty”) set him trembling with desire. “I knew I was approaching the spot where the treasure lay buried.”

At 18 daddy’s trust fund kicked in. After a jaunt to Paris where he launched a narcotic habit, Horsley moved to Edinburgh and became friends with imprisoned Glasgow gangster Jimmy Boyle, a convicted murderer whose specialty was gouging out eyes. We learn that Boyle “invented the dirty protest,” covering himself in his own poo to deter prison guards.

Bash seemed to be falling in with the wrong crowd. A mitigating factor was his roommate and best friend, Steve. In their Edinburgh flat one night, Steve came out to him — and Horsley began to wonder if gay life “was the way to enlightenment.”

In 1982, now at art college in London, he bought a book by Ernest Becker. The Denial of Death convinced him that his shit was a profound preview of life’s final exit. Horsley locked himself into his Soho flat to play softball with the Grim Reaper: three days of total scat immersion. His candour here is breathtaking. I was glued to the page. Then I couldn’t stop wondering how he cleaned death off the walls and carpets.

Around this time he fell out of love with his Scottish girlfriend, then agreed to marry her. Here Horsley begins to underscore his categorical distaste for women — and I began to lose any vestige of respect I had for his subversive soul. Here’s his memory of the wedding ceremony: “Ev gazed up at me with her big, bug eyes. I stared back, astonished. Women: sometimes murdered, often deserted, rightly ignored.” Is this meant to be edgy humour? It sounds like open hatred.

His real love was for Boyle. Once out of prison he and Horsley became codirectors of a Scottish prison reform program called the Gateway. Admirable work, and Horsley vividly describes the pitfalls, marginal successes and endless frustrations of it. Meanwhile the inner Horsley seems more like a retro homo forever in denial about where his cock points, even as he reveals exactly where his heart rests — with Jimmy. “As far as we were concerned only men had the wings for love and no one else, especially our wives, could flutter up to our fire.”

In a hotel room after a drunken party, Boyle and Horsley were blotto enough to finally consummate. Morning brought a new outpouring of love: “Boyle had fucked me all night and I couldn’t keep my shit in” — which is exactly Horsley’s problem as a writer. He wields his candour like a shotgun loaded with dreck. He can occasionally be spot-on about the cruel ways of the world, but too often his broadsides and shallow ironies are simply childish and bigoted.

Through it all he never finds a self he can live with. Coming down from his precarious high with Jimmy, he tried to reconfigure his desire. He bought sex from hundreds of women, then switched to selling it to them as a high-end ladies’ escort. His crack addiction ramped up to heroin, while his impulsive suicide attempts never quite had the punch to succeed. If he weren’t such a desperate show-off all of this might be sadly touching, possibly tragic, but even Horsley’s shrink couldn’t penetrate his constant posing. In his final chapter he poses as Christ, nailed to a cross in the Philippines. It triggers some of his better writing, briefly.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra