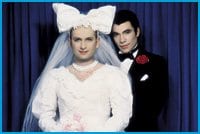

CAMP AS TITS. Gilles Blanchard and Pierre Commoy love to include themselves in their art. Credit: (LES MARIÉS, PIERRE ET GILLES, 1992)

When I was but a young gay, much too shy and easily intimidated to actually browse through porn magazines in public, I would get my nudie thrills in (where else?) the art section of whichever bookstore I found myself.

Which is how I found Pierre et Gilles. Amid their absurdly campy painted photographs of friends and celebrities dolled up as anything from hustlers and Hindu gods to Jesus herself, in addition to the copious amounts of nudity there was, God bless them, even a hard-on or three, a godsend for any young queer desperate to find a reflection of his desires.

On the occasion of a recent retrospective show in Paris, Taschen has just released Double Je (literally, “Double Me,” also a French pun on double jeu, meaning duplicity or double-cross), a Pierre et Gilles monograph of encyclopedic proportions, cataloguing almost every image ever made by the duo in their 30 years of personal and professional collaboration. If my younger self had managed to get his hands on it (if I’d even been able to lift the damned thing) my head probably would have exploded.

Pierre (né Commoy, the elfish one with the dark hair) and Gilles (né Blanchard, the round-faced blond) both grew up in small French towns, Pierre in La Roche-sur-Yon in western France and Gilles in Le Havre, before going to art school (Pierre in Geneva, Gilles in Le Havre) and making the trek to Paris to find fame, fortune and love. Both got their start in publishing: Pierre took photographs for fashion and music mags and Gilles did illustration work in advertising. They found each other in 1976 and promptly began a life’s collaboration: Pierre would take photo portraits and Gilles would paint over them (that’s where that polished, plastic look comes from long before Photoshop) and embellish the backgrounds.

They began doing portrait work for Façade Magazine, an upstart underground celeb and fashion rag modelled on Warhol’s Interview. Despite its amateur business practices (tiny print run, no publication schedule), its addiction to the cutting edge made it a highly sought-after cult item and attracted higher profile interviewees. It effectively launched the duo’s careers, landing them the opportunity to work their magic on La Warhol himself, Mick Jagger, Iggy Pop, Yves St Laurent and others. Collaborations with fashionistas (Thierry Mugler) and musicians (Amanda Lear, Françoise Hardy), as well as high-profile ad campaigns followed. Their first inclusion in an art gallery came along in 1982 in a group show, followed by a solo show in 1983. The rest is history.

Pierre et Gilles are by now icons of queer art.

Granted their heyday is a few years gone — in the mid-1990s you couldn’t swing a limp wrist without hitting a magazine cover, movie poster or CD album art of theirs. Still their instantly recognizable images endure as a high watermark of gay art. They have also carved for Pierre et Gilles a place in the pantheon of photography and this catalogue, in all its 450-odd page breadth, offers a pretty convincing (and utterly gorgeous) reason as to why.

One piece of advice: Skip the essays as their part of the argument is neither convincing nor gorgeous. Art gigastar Jeff Koons offers what has to be the most vacuous 20-line introduction in the history of the written word. Paul Ardenne offers an in-depth interpretive essay as an afterword. It is painfully overtheorized, which would be bad enough if the sloppy translation from the original French didn’t make it even worse.

Neither of these two gets in the way of the star couple of the book.

Taschen is, of course, a veteran of these kinds of mega-glossy art tomes (not to mention the fact that they’ve put out numerous other Pierre et Gilles volumes in the past). The book’s design is what you’d expect: just enough bombast and pizzazz to let you know that this is a Taschen book without getting in the way of the art.

The artworks are arranged in thematic, as opposed to chronological, order. The only chronological section — a scrapbook-style “illustrated biography” from 1950 to 1979 cataloguing their respective youths and their early career together through various personal ephemera — will thrill Pierre et Gilles connoisseurs.

Once the photographs proper begin the book runs through the central themes that Pierre et Gilles have been exploring for three decades now: celebrity, religion, sexuality. While their aesthetic has been pretty much set in (rhine)stone for a while, the page-by-page juxtapositions of early and later work is interesting to see.

When you think of a Pierre et Gilles image you think of their later photos: the James Bidgood inspiration, the immaculately polished painted-over photograph theatrically posed amidst radiantly colourful and gloriously kitschy sets, the artifice, the glamour, those hot hot boys that seem to grow only in France.

I was, in fact, surprised to see just how different are the early works.

Granted the essential elements are constant (the painted photograph, the kitsch, the hot hot boys) but the early works, with their flat painted backdrops and blaring colours, have a confrontational effervescence that doesn’t make it into their more iconic work.

This is not to denigrate that later work; greater fame afforded them bigger budgets and better means by which to explore the universe of their imaginations.

By now that universe has been fleshed out with such success that it has left an indelible stamp on the queer imagination. This is the book’s (and Pierre et Gilles’ for that matter) great success: It uncovers every corner of that universe, maps every metamorphosis, from its brazen beginnings to its fabulously tacky iconic landmarks, and counts every blessed hard-on along the way.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra