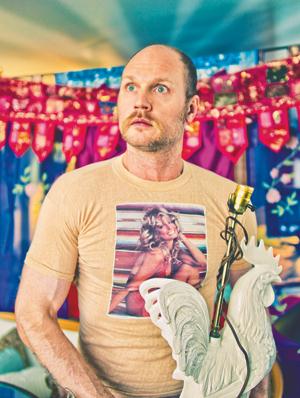

Credit: Augusten Burroughs

“The most important thing to remember about George Orwell,” remarked the late Christopher Hitchens, “is that he was not a genius.” Though one of the great moral centres of 20th-century letters, Orwell never attended university and managed to produce his prodigious output without the luxury of a higher education. What Orwell did possess, Hitchens concludes in his study of the author, was the “X-factor [of] intellectual honesty.”

Like Orwell, Augusten Burroughs never attended university and is in possession of a similarly invaluable X-factor. Burroughs’ career was launched with the publication of his memoir Running with Scissors. Although Burroughs convinced himself the book would be a flop — even downloading applications for a nursing program at a community college with the aim of becoming a hospice nurse —Scissors established him as an internationally acclaimed memoirist. The success was followed by the memoirs Dry, Magical Thinking, Possible Side Effects, A Wolf at the Table and You Better Not Cry, each book typified by Burroughs’ mordant wit, pitch-black humour and searing introspection.

In his new book, This Is How, Burroughs borrows a line Orwell wrote in an essay for the London Tribune: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” When I ask if Orwell is an influence, Burroughs chuckles and, with typical unpretentious candour, admits, “You know what? I’ve never read anything by George Orwell except for that quote.”

With This Is How, Burroughs expands his oeuvre into the oft-maligned world of self-help. However, anyone expecting tidy platitudes and warm affirmations should be cured of that illusion by the book’s subtitle: Help for the Self: Proven Aid in Overcoming Shyness, Molestation, Fatness, Spinsterhood, Grief, Disease, Lushery, Decrepitude and More for Young and Old Alike.

I spoke with Burroughs in the lead-up to a book tour that will bring him in contact with his loyal — and enormous — fan base. Burroughs, a self-taught polymath, is able to wax poetic on many subjects, and our conversation touches on chemistry, the nature of time, quantum physics, literary fame — “I don’t ever fucking think about it” — the importance of truth, and even the existence of god. “Maybe there’s many heavens and maybe there’s not,” says Burroughs, “but I think people need to live as though there’s not.”

Xtra: Your fans tend to speak about you as though they know you personally. Do you get that a lot from people?

Augusten Burroughs: I do get it a lot and, you know, it’s true. People who’ve read my previous work really do know me. I mean, they don’t know all of me, but they know a lot of what goes on in my head because I don’t really filter.

People feel as though you’re really speaking to them.

I think that’s a great compliment because, at least in my experience, I don’t write for an audience; I don’t have a particular person in mind or a group of people in mind. I think if I did have such imaginary people in mind, I would end up speaking to nobody. So, I really write for myself. Even with the new book, which is about you — the collective you — I end up explaining things in ways that make sense to me. I’m going through my thought process or I’m explaining how I have solved issues and what I have come to believe about certain things. When I am able to communicate with myself — in other words, when I’m able to get to the truth of what I feel or think or believe — that resonates with people because it rings bells within them as well.

You seem to have invented a genre — the memoir-self-help book.

It’s a different kind of self-help book. It’s not going to work for everybody because some people aren’t going to want to do that kind of work. When you’ve got problems or obstacles in your life, or things that you need to get over or move beyond, or emotional baggage, you can get rid of it, but there’s also often a price to pay. Sometimes the price you pay is the dismantling of some part of your world that you are not ready to dismantle or that you don’t want to believe you have to dismantle. So, not everyone is going to leap right in, but those who do, I think, will find some success with it because it’s worked for me.

Would you say that the power of the book is about a searing, razor introspection?

It does require absolute honesty with oneself, and that’s not a difficult thing to do for anybody, but it can be very uncomfortable, and you can be fooled into thinking it’s difficult. In my own life, when I’ve been lying to myself about something and I pause to consider my circumstances and think about ‘Why am I still fucked up in this area?’ the answer I often come up with is no answer at all, and when I have no answer at all, that’s my clue. Whatever the answer is, it’s so obvious I can’t see it. The truth can be so close that you refuse to see it or it just seems too painful to see, but that’s why you have to keep hammering away at it.

I get the sense that you don’t believe in this tidy notion of closure.

Yeah, even the word itself annoys me. It’s so pat, and there’s very little in the world that is that pat and that absolute. I don’t think that for the majority of people in the majority of circumstances closure is realistic. Certainly in the break-up of a relationship you’re not going to have closure. Closure is also vague; it doesn’t say specifically anything, so I think that when someone decides to seek closure, that’s when I want to say, “Hmmm . . . what is closure?” Vagueness is unhelpful. Healing is another word that’s bullshit — what does that even mean? If your child dies you’re never going to heal. So what is “heal”?

You might get this question a lot, so I apologize if it’s a bit of cliché, but do you believe in catharsis?

I don’t write with catharsis in mind. That’s not the goal of it, but it’s different things. When I sit down to write a collection of essays, I often have nothing in my head at all, and I can’t remember a thing. I have to really get into a place in my head that I can just slide back into at will, which I enjoy. It’s like having a shoebox at the back of your closet that you put there 15 years ago and forgot about. So there’s that aspect of it, which is nice, but I don’t necessarily think it’s particularly cathartic.

But is a part of your goal to try to help people? Is there a therapeutic element to your work?

That’s my whole goal. I look at it myself as almost a career change. I’m not going to write more memoirs and short-story collections about me; this is what I want to do. It weighs more, it matters more, it’s more satisfying. It’s something I’m good at and it’s something I care about. I think of this book as not a collection of stories about “Look at all I’ve survived; look at all these things I’ve made it through!” It’s about how I made it through those things, and there is a definite application to other people and their own lives.

Are there any overarching themes that you find yourself coming back to?

I’ve never really reflected on it, but I just try to live my own life as honestly as I can because every time I lie to myself I get disappointed or stuck. So, my whole life — since I was a kid — has always been about trying to get to the root, to the essence of the truth, to the core. It’s just my nature. So I guess if there’s any kind of theme, it’s just getting to what is the truth, no matter how ugly it is, because if you know what the truth is you can clean it up and deal with it. If there’s something rotten at the inside, you’re going to stink.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra