In the summer of 2022, a coach reached out to Casey Rothschild, a five-time competitor on American Ninja Warrior, and founder of Queer Ninjas Unite. One of their young athletes, a non-binary competitor, was struggling to choose between the men and women’s division of their local ninja league, and might forgo competition entirely. Could Rothschild help?

Rothschild, who founded Queer Ninjas Unite in 2020 to create a safe space for LGBTQ2S+ competitors, went to work. She canvassed non-binary athletes, most of whom concurred: “Some athletes would be okay with [competing] in a gendered division,” Rothschild says. “But most would not compete without an additional division.” And while there are no barriers to training ninja as a trans and/or non-binary athlete, competitions are another matter. All ninja leagues, from the World Ninja League to the Canadian Ninja League, divide their participants according to gender.

In American Ninja Warrior, a spinoff of the Japanese television special Sasuke, competitors attempt to conquer obstacles over a series of increasingly more difficult courses until only one (or none) of them remain. Now in its 15th season, the American version not only has multiple spinoffs (ANW Junior, Ninja vs. Ninja), but also inspired an entire sport with dozens of leagues, hundreds of gyms and tens of thousands of athletes competing in recreational leagues. The sport, which is a hybrid of parkour, CrossFit, rock climbing and acrobatics, requires a combination of problem-solving, upper body strength and agility. ANW is a sport built around failure: competitors usually only get one shot at each course, and in finals, a single fall means the end of someone’s season. In 15 years, only a few people have successfully completed all four stages of the national finals; only three have ever won.

American Ninja Warrior stumbled into its reputation for gender inclusivity. Following Sasuke’s example, athletes of every gender ran the same course and battled the same obstacles. While the sport was dominated by men, it was history-making runs by female athletes that gave ninja both cache and mainstream coverage. Viral runs by Jessie Graff, Kacey Catanzaro and Megan Martin have amassed over 45 million views on Youtube (in comparison, Isaac Caldiero’s show-winning run only has five million views, despite the fact that he is the first person to win the million-dollar jackpot by completing all four stages of the Vegas Finals). The show’s obstacle courses were so difficult that watching women conquer obstacles that stymied male competitors accidentally turned ANW into a promotional vehicle for the strength of female athletes—and the benefits of gender-neutral competition.

The show also quietly supported its queer competitors. The show places no limits on trans participation. American Ninja Warrior competitor Jensen Little explained to Queer Ninjas Unite that “leagues and gyms showed no hesitation in allowing me to compete in male divisions once I began my transition.” ANW has also featured non-binary competitors in its spinoff ANW junior. In Season 13, the show aired a Pride segment to go along with Casey Rothschild’s run, and has aired several segments on Queer Ninjas Unite’s platform since. This year’s Stage 1 finals in Vegas included a segment on Barclay Stockett, a five-time qualifier to nationals and one of the sport’s most well-known female competitors, and her life with her fiancée, fellow ninja Tee Jackson.

Advertisement

Outside of the show, however, it’s a different story. Wolfgang (who prefers to go by first name only), a manager at Brooklyn ninja gym, started training ninja when he was around 14. At the time, he was transitioning; at his first ninja competition, he had to sign up under his legal name. “It was very weird [being] on the female podium,” Wolfgang says. “If I were interested in competing more, I would have struggled.” When recreational ninja leagues began in 2015, they placed men and women in separate categories: competitions for athletes as young as seven are divided by gender. Queer Ninjas Unite profiled multiple non-binary athletes who struggled to compete because of the gendered divisions. For Jax Greenbaum, a ninja athlete, “having to choose between the men and women’s division does not work for me as a non-binary person … because I know it will not feel right, I am discouraged from competing.”

Back at Queer Ninjas Unite, Rothschild was stuck. Major ninja leagues were cautiously interested in a gender-neutral division, but kept from committing. Cost was a concern—an extra division would mean more prize money. More existentially, leagues worried that member gyms would not be on board with a gender-neutral division, and could pull out entirely (Xtra reached out to several ninja leagues, including World Ninja League and the Canadian Ninja League to ask questions about their trans inclusion policies, but did not receive an answer). Meanwhile, one of the largest leagues, the Ultimate Ninja Athlete Association (UNAA), was explicitly trans-exclusionary, with its rulebook stating that “any transgender athlete competing in UNAA competitors must compete in their gender assigned at birth and follow the Fairness in Womens [sic] Sports Act: 461.” The Fairness in Women’s Sports Act refers to legislation passed in 2020 and 2021 in Idaho, Florida and Arkansas, which requires sports sponsored by public schools to restrict participation based on an athlete’s gender assigned at birth. Because UNAA is a recreational league, not a public educational institution, it has no legal obligation to comply with the Fairness in Women’s Sports act, which means the UNAA’s decision to comply by the law is entirely ideological.

But where major leagues balked, one league, Northeast Ninja Association (NENA), took up the challenge. “In other leagues over the years, athletes had come through—especially younger athletes—who were in this weird position. The leagues were caught in this ‘I don’t know what to do phase,’” Dave Cavanagh, president of NENA, which represents 19 gyms across Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, New Jersey and Connecticut, explains. “It seemed like a no-brainer to at least try. By implementing [all-gender divisions] on a smaller scale, we could give an example on how it would work.” When Queer Ninjas Unite put out a call to action, NENA responded. Soon, Cavanagh and Rothschild were working to build a gender-inclusive division.

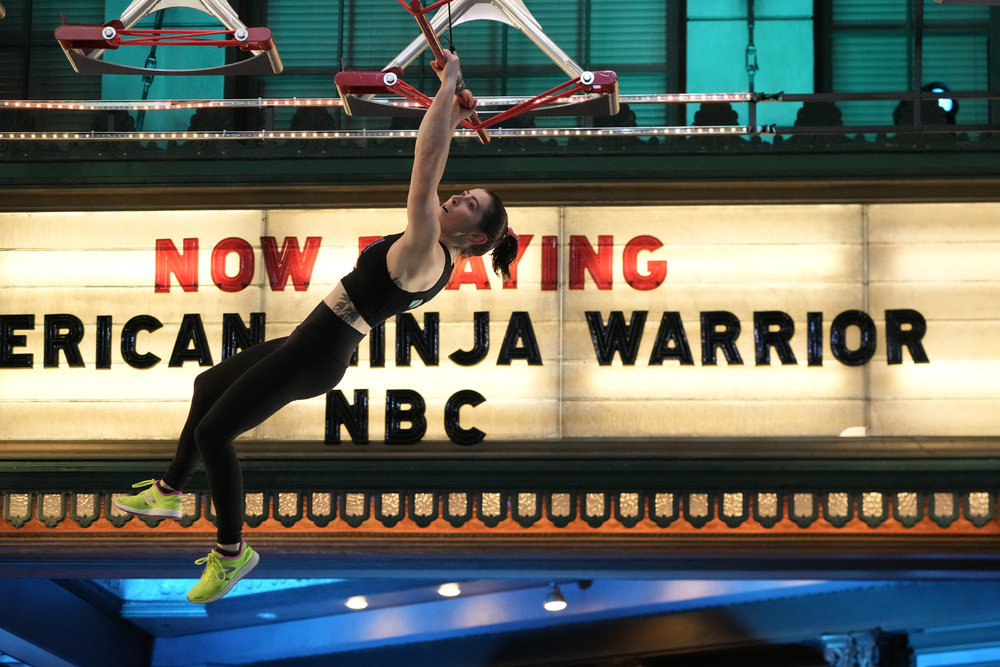

Casey Rothschild on American Ninja Warrior, Season 14, Women’s Championship Credit: Elizabeth Morris/NBC

NENA ran into surprisingly few roadblocks in preparing for the 2022–2023 ninja season. A couple people brought up questions about fairness: what if someone abused the new division to win more easily? “With ninja, there are so few stakes,” Rothschild says. “There’s no real money in it. There are no college scholarships on the line. It’s not the Olympics. And you don’t want to be body-checking teenagers. [I] appreciate how quickly NENA was like, ‘that makes sense.’”

The next question was what to call the new division. At first, NENA considered the term “non-binary division” but non-binary athletes pushed back, as that label would require competitors to out themselves. Instead, the division became an “all-gender division,” which not only created space for non-binary athletes, but, in a throwback to American Ninja Warrior’s origins, allowed athletes of all genders to compete against each other.

As a new sport in a smaller community, Ninja Warrior practitioners have room to experiment. Countercultural sports like skateboarding, breaking, parkour and ninja often attract athletes who don’t fit in conventional sports. That includes a disproportionate number of LGBTQ2S+ competitors, for whom the lack of regulation in newer sports is attractive. The lack of standards is an opportunity: without fixed rules, athletes can improvise, find creative solutions and experiment. These experiments include gendered ones: several newer sports start without gender segregation, or include mixed-gender teams.

But what happens when a new sport grows beyond its experimental stage? ANW began as an annual special on the now-defunct cable channel G4. Now the show airs on NBC, where it averages three million viewers an episode—six million at its heights. Last year, the Olympic sport of Modern Pentathlon voted to add “obstacle racing,” with obstacles that were inspired by Ninja Warrior, as its fifth discipline. Pentathlon’s last-minute bid to attract more viewers (the IOC is planning to cut Pentathalon for Los Angeles 2024 because of viewership) signals ninja’s drawing power, fuelling hope that ninja could become an Olympic sport—something several leagues are actively working toward.

Ninja is running straight into a problem subcultural sports face when they receive mainstream approval. As Dvora Meyers writes in Vice, the “elevation, celebration and grand recognition of the global stage” that comes with Olympic recognition flattens the sport’s original subcultures. The experimentation that defines new sports is sacrificed for global attention. No matter their origins, for sports with Olympic aspirations, separating genders is de rigueur. The last four sports added to the summer Olympics—sport climbing, skateboarding, breaking and surfing—all have a separate men’s and women’s event. There are good reasons to promote women’s events: they bring more attention and compensation for women athletes, who often struggle to make a name for themselves in the male-dominated field of athletics. At the same time, it also represents the IOC’s unwillingness to experiment with sports structures that allow athletes of all genders to compete against each other without disadvantaging women.

Breaking—and staying—in the mainstream demands a level of conformity. As ANW’s ratings plummeted from their highest point, the show made a series of format changes to reverse the trend: adding younger athletes, cash prizes and, most recently, switching the format to feature two ninjas racing against each other. This format switch was the death knell for the show’s former gender equity. A few years ago, the show’s rules changed to guarantee that a number of women would advance to the national finals. Now for the majority of ANW, men and women no longer compete against each other at all.

Ninja is not a typical countercultural sport. When I asked Rothschild, a two-time national finalist, why there were few openly queer ninjas, she related her experience at the show’s finals, where she found herself one of a handful of ninjas who did not participate in group prayer before the semifinals. Why, she wondered, was ninja so more Christian than related sports like climbing? The answer is simple: ninja started not as a sport, but as a reality TV show. Pitched to middle America, the show not only reflects mainstream American culture—it can’t afford to be countercultural. “Every time I talked to [people on the other side of the camera], they were trying to remain as neutral as possible against anything that could put a target on them,” Cavanagh, who has competed on ANW 10 times, says.

While ANW welcomes queer competitors, it has a vested interest in staying quiet on issues that alienate their base. When Rothschild came out to run 2020 with the Bisexual Pride flag, Cavanagh was shocked that the show allowed it—and made an entire Pride storyline to go along with Rothschild’s display. The show highlights certain athletes through feature backstories that proceed their runs: after 15 years, only two explicitly queer stories have been featured on the show, Rothschild’s and Stockett’s. Meanwhile, athletes with explicitly Christian storylines and nicknames like “the Papal Ninja,” “Kingdom Ninja” and “Ninja Pastor” are ANW mainstays. The show rarely tells stories about being queer (and never tells stories about being trans), at least not the way it features stories about being a mother, being a religious leader or even having a mildly unusual job (cowboy, cat sitter, ax-thrower).

Yet ninja could be very different from its more conventional TV origins. Queer Ninja Night is a new invention, organized by Wolfgang for his gym. The first such event in NYC (and possibly the United States), Queer Ninja Night started as a one-off Pride Month occasion, but it was so successful that the gym turned it into a monthly event, with more attendees coming out every time. It brought a lot of people into try [the sport] who might otherwise not have come to try ninja,” Wolfgang says. At the September night, cis men were a small minority of attendees, and the average age trended upward of thirty—a far cry from ANW’s typical pool of athletes, who skew young, male and white. Participants discussed binders, climbing and fitness strategy as as they took turns swinging on upper-body obstacles.

Including LGBTQ2S+ athletes benefits the entire sport. Northeast Ninja’s all-gender division ended up a rousing success in the 2022–2023 season. “[The division] didn’t make people feel alienated; it didn’t just have one person going,” Rothschild says. “Instead, it was for non-binary athletes, and for people of all genders who wanted to compete against each other.” Feedback was universally positive. “A lot of people were like, ‘I wish I’d known about it earlier’,” Cavanagh says, with many athletes excited to switch to the all-gender division for the upcoming ninja season.

Cavanagh and Rothschild both hope that NENA’s success will only open the door for other leagues—and other sports—to create their own all-gender divisions. At a time when more and more youth and recreational sports are taking steps to curtail participation by trans and non-binary contestants, NENA’s throwback to ANW’s gender-neutral roots provides a different way forward. “Ninja has the potential to be a lot better [for queer competitors],” Wolfgang says. “It fosters community in a way that other sports don’t.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra