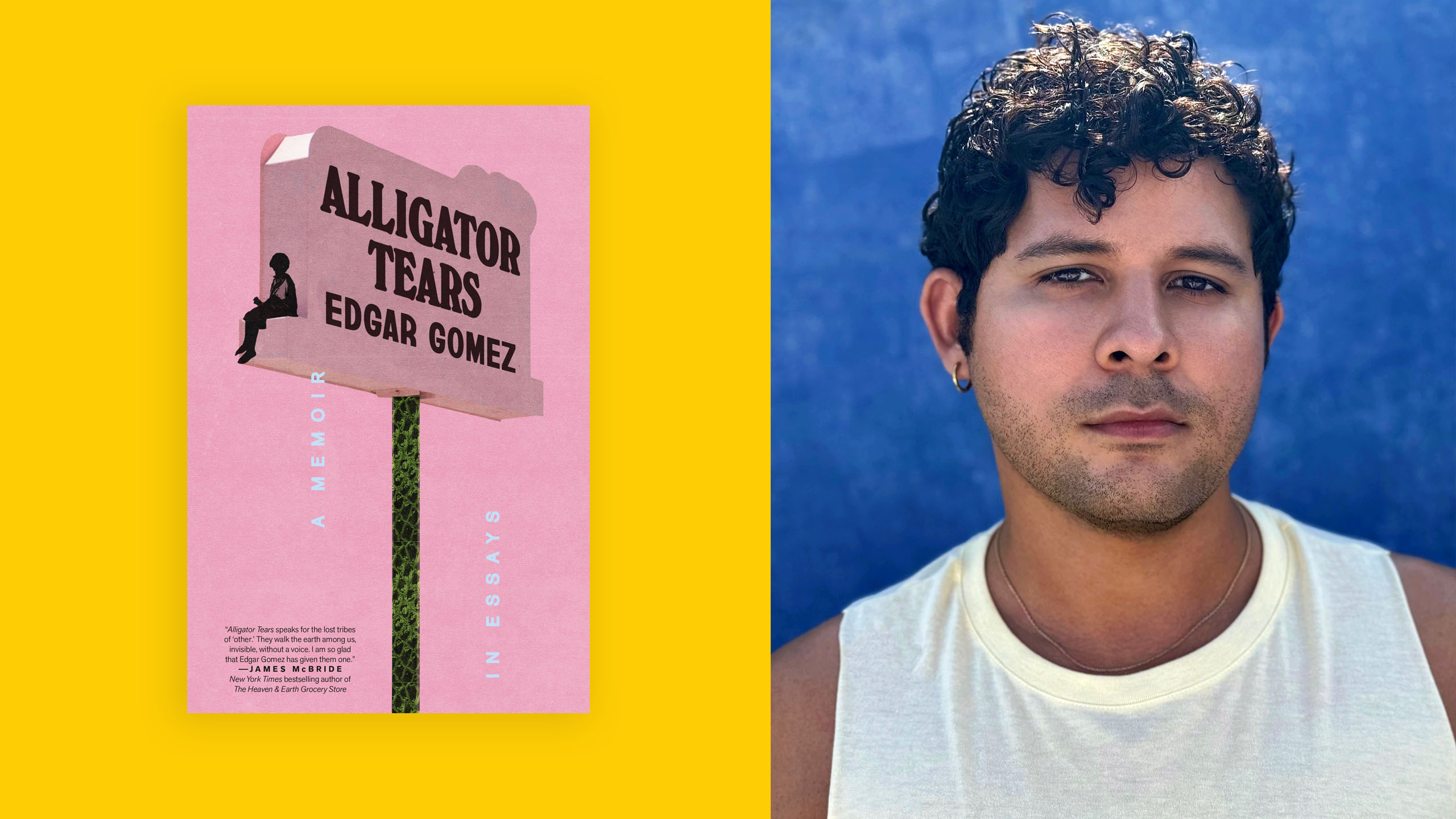

Alligator Tears is the second memoir by Florida-raised, New York/Puerto Rico-based writer Edgar Gomez, following 2022’s High-Risk Homosexual. This might be surprising to readers, who might wonder, given that Gomez is only in his early thirties, whether he has lived enough to generate two books’ worth of self-reflection. However, Gomez’s decision to write into the recent trend of the memoir-as-essay-collection allows him to examine incidents and periods in his life from a variety of perspectives; he treats his lived experience like a prism, letting the sun shine through one facet at a time. Gomez has a dizzying array of stories to tell in his charming, conversational manner. At his best, he upends assumptions about queer working-class Latinidad, no matter which angle he is writing from. In High-Risk Homosexual, Gomez mined his experiences and self-reckonings through the lens of queer Latinx coming-of-age narrative. Alligator Tears often sees him revisiting experiences from the previous collection through a different lens, that of growing up poor in Florida, and continuing to live with financial precarity as an adult in New York and elsewhere.

Writing for Lit Hub, Elizabeth Kadetsky points out the differences between the linear memoir and the more fragmented memoir-in-essays: while the more traditional memoir focuses on seeking redemption over the course of a life, the non-linear structure of an essay collection allows the memoirist to write into uncertainty, without the need for a clear resolution. “Bad things happen for no reason; overcoming one trial does not lessen the need to adapt in the next.” This aptly describes Gomez’s project in Alligator Tears, which is a chronicle of growing up poor and queer and Latinx, and of being a queer Latinx adult who strives to write and has to maintain countless side hustles and low-wage jobs in order to make that happen for himself, while supporting his mother, a chronically ill low-wage service industry worker. There is no “happy ending” to attain, no wealthy Prince Charming to sweep Gomez off his feet, no six-figure book deal to solve all of his anxieties. What there is, is Gomez’s dedication to humour, love, community activism, femme power, honesty and scrappiness, all of which propels these essays far more compellingly than a linear rags-to-riches narrative could ever do. Bad things do continue to happen to Gomez and the people in his life, and they all figure out how to deal with those things, stubbornly and creatively, with a mixture of optimism and pragmatism.

Like High-Risk Homosexual before it, Alligator Tears is a somewhat uneven collection. High-Risk Homosexual’s best essays were the ones in which Gomez allowed himself to write about complex people and situations, while trusting his audience to pick up on nuance without him needing to spell it out. Some essays in that volume, like “Mama’s Boy,” about a fraught but life-expanding friendship between teenaged Edgar and Miguel, a slightly older and much more worldly drag queen, were compelling and surprising—but others felt rushed and prone to over-explanation, as if they were written for readers who were largely unfamiliar with queer life. The first few essays in Alligator Tears, which plumb Gomez’s childhood, sometimes feel similarly rushed or oversimplified; there is a somewhat generic aspect to their language and their conclusions. “The room shrank, the walls closing in on me,” Gomez writes, describing a scene in which he is questioned by police as a teenager, and falsely implicated in a rich white student’s weed-dealing. The walls closing in on a stressed-out person is such a common image that it reduces the impact of what must have been a harrowing experience. In the same essay, after his Myspace crush deletes his account, teenaged Edgar wonders: “Can you lose something you never really had?” The question feels a little obvious or easy; I found myself wishing for a more surprising or unexpected reaction or reflection. There is nothing wrong with plain, accessible language; however, these first few essays don’t always feel fully alive.

As the collection moves into Gomez’s more recent experiences, however, the essays sharpen notably, with Gomez describing and reflecting on his recent years in vivid, absorbing detail. “My Body of Work” is a propulsive text that chronicles Gomez’s various gigs and side hustles, from selling expensive flip-flops to Florida tourists, to hawking bootleg CDs at the flea market, to doing sex work in a New York club—part of the job that the bosses were not upfront about. The prose flows in a hypnotic stream, as Gomez’s low-wage jobs begin to blur and overlap with each other: “This gig pays me pizza, another in exposure. I’m thrilled about a twenty-five-cent raise. My friends all Venmo each other the same emergency twenty dollars over and over … I wake up smiling maniacally, asking the air if it’d like fries or coke with that order.” The essay treats sex work as work, pointing out that Gomez’s retail bosses were constantly telling him what to do with his body all day, what he has to wear, how he has to move, where he has to go. When he makes the occasional choice to get paid for sex via the apps, or elsewhere, he doesn’t experience much of a difference. “Don’t get me wrong,” he writes, “I’m not saying it’s the same. There are people who would rather starve. What I’m saying is that I wasn’t one of them.”

In “My Boyfriend, His Lover, and Me,” Gomez finds himself in a poly situation with Diego, a young queer working-class Latinx artist like him, and Diego’s other boyfriend, a famous older white gay artist. Gomez offers the kind of love and understanding that comes from so many overlapping shared experiences, but the famous lover can offer Diego material comfort and financial stability. In true “Jolene” style, Gomez imagines himself confronting his celebrity rival: “You have so much! You have money. You’re a celebrity. You’ll find someone else. I know it’s up to him to choose, but it’s not really a fair match, is it?” Here, his desperation to hold on to his first love, to share the stresses and pressures of being poor and in Diego’s case, with precarious status in the U.S. We feel this thanks to Gomez’s tender portrait of their relationship, like this scene in which Diego makes them both dinner in his tiny kitchen: “I felt both dizzy and giddy thinking about how this domestic scene looked nothing like the heteronormative relationship models I’d been brought up with. He was the top. I was the bottom. I was supposed to be making him dinner, and he was supposed to be nursing a beer on the couch. Yet here we were, creating something new.” In the end, Gomez accepts the relationship’s end with grace, but the heartbreak of it stays with him for some time.

“Images of Rapture” has Gomez trying to support his mother from afar during the early COVID-19 pandemic; he is stuck in New York trying to figure out unemployment benefits, while she is stuck working at the airport Starbucks in Orlando, required to continue putting herself at risk so that the people who are still flying can have their coffee. During this period, Gomez also takes a break from working on his first manuscript to get involved in a queer food pantry in his neighbourhood in Queens, which leads to new friendships and a new boyfriend. Through the pantry, he also gets involved in the Mirror Cooperative, a non-profit beauty certification program started by two trans women in the neighbourhood to offer beauty classes to trans Latinas. Modelling for the students, and allowing himself to get into full made-up femme mode, and being fully supported and appreciated there, including by his new boyfriend, gives Gomez a sense of relief and peace. “Something began to thaw inside me,” he writes. His femininity no longer feels like a liability, the way it used to.

The essay draws from the activism and solidarity of the people he meets at the pantry, to reflect on the ways in which poor, queer, trans and racialized people make change within oppressive systems and circumstances. “Early on, Mom taught me that if you weren’t satisfied with the present, there was always the dream of ‘one day’ to look forward to,” he recalls. Alligator Tears sees Gomez contending with this belief—how it bolsters him and his mother through bouts of financial, medical and emotional stressors, and how, at other times, it renders them inert. Waiting and hoping for change isn’t enough, he decides as he matures. He learns to make plans and take action, which includes exploring his own queerness and femininity despite homophobia in his family and at school; daring to become a writer even when it is not an obvious route to money-making; moving cities and working a long string of low-wage jobs to get by; and holding on to hope for that “one day” while hustling in the present, amongst friends and wider queer and Latinx community. By the last essay, he comes to realize that being queer, though it has led to rejection and pain at various points in his life, has also made him into the kind of person who takes risks, who does more than just waiting for better things to come to him, that being queer pushed him to leave where he grew up in search of more.

There were some points when I wondered whether culling the strongest essays from both books and publishing those as one incisive volume might have been a good choice. An emotional but somewhat predictable-feeling essay in Alligator Tears about the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, where Gomez came into his own Latinx queerness, might have been even more impactful if it were published alongside or even edited together with Gomez’s other Pulse-focused essay in High-Risk Homosexual, which traces the life trajectory of the Pulse shooter, Omar Mateen, comparing it unsettlingly with his own. If we’re lucky, maybe we will get a “best of” collection of his work later on in his career. Gomez’s writing is most powerful when he walks the line between tenderness and discomfort, between his abundant humour and the discouraging, grinding realities of being poor in America. The strongest essays in Alligator Tears offer us stories of struggle, resistance and community-building by queer, working-class, racialized people living in an increasingly polarized, unaffordable and fascist America. In the last piece in the collection, Gomez, panicking about a new piece of bad news he has received during a rare period of calm living in Puerto Rico, struggles against the temptation to give in to uncontrollable forces, to let himself sink to the bottom of the ocean he is swimming in. Then he remembers what he learned as a kid in Florida: If you ever feel like you’re drowning, float on your back, let the water do the work of keeping you breathing, while you gather your strength to keep going. Alligator Tears gifts us with lessons on remembering how to float, how to keep breathing, despite all of the forces that would have it otherwise.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra