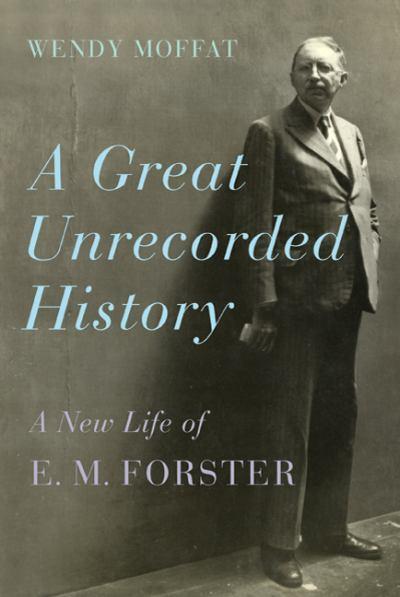

In this new EM Forster biography, Wendy Moffat gifts readers with details about the man behind such novels as A Room with a View and Howards End. Drawing from Forster’s relatively recently discovered letters, Moffat examines the writer rather than the writing. Forster’s portrayal of the class struggle in Britain and his pacifist views were often lonely cries among the drums of war beating in the early 20th century. He wrote from the closet, the well of his passions and discomfits, for most of his life.

At its heart, Moffat’s work examines a mystery: why did Forster abandon writing novels after his fourth, A Passage to India, published in 1924, was recognized as a masterpiece by critics and the public alike? Instead of writing, Forster had numerous sexual successes, volunteered for the Red Cross, travelled, lived with his overbearing mother and surrounded himself with working-class friends instead of the artistic entourage that might be expected.

Although Unrecorded has a lot of heart, it is not critical. While a gratifying revelation for those wanting to know the man, those wanting to assess his work should look elsewhere. Moffat acknowledges his critical reception but little more. Unrecorded is, though, an intense look at a man who dearly wanted companionship.

By many accounts, Forster inspired admiration, love and respect from those who knew him. Often aspiring writers discovered his books and sought him out. That he managed a triad with the love of his life, Constable Bob Buckingham, and Buckingham’s wife, May, is astounding. For a time, he spent long weekends with Bob, while May had Bob for regular weekends.

Moffat also argues for Forster, in his decline, bridging the generations between queer writers and artists. She succeeds, firmly establishing his place in the literary canon, queer or not. Although he was not writing, others clearly recognized his genius. While his contemporaries were DH Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, the Bloomsbury circle and Christopher Isherwood, a new generation of Americans also longed to meet him. People such as artist Paul Cadmus, actor William Roerick and painter Jared French eventually became acquaintances of the Great Writer.

Severely cerebral, Forster did not sleep with a man until age 37. Moffat, generally wordy and insightful, mixes the callous with the profane both here and in a few other passages.

“It was embarrassing to be so sexually belated, at thirty-seven to not have any more sexual experience than these terrible cravings of lust and an occasional wank under the stars.”

However, Forster compensated for lost time with pursuits that Brian Kinney of Queer as Folk would have respected. In 1916, on a beach in Alexandria, Egypt, he found a soldier “as hungry as himself,” “parting with Respectability.” Moffat off-handedly theorizes a hurried sucking off.

Moffat depicts being closeted and the fear of being discovered as the forces that drove Forster to display the class struggle. Moreover, Forster suppressed Maurice, a novel that not only let gay love speak its name but granted it a happy ending. Forster, however, dared not publish this highly personal work while still alive. All the while, he longed for an enduring queer love. That this mousey, attentively listening figure stirred those around him and was about 50 years ahead of his time in themes of gay love is heart-rending. Moffat, in turn, renders this discovery of Forster heart-rending.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra