On a sunny day in April last year, at an ocean-side resort just steps from one of Barbados’ famous white-sand beaches, a hate group was hosting a conference.

Dozens of neatly-dressed church and community leaders, including a Barbadian senator, packed into meeting rooms and diligently took notes as speakers opined on the evils of abortion, contraception, sex education and LGBT rights.

The World Congress of Families, one of the largest and most influential anti-LGBT networks in the world, had invited a murderers’ row of homophobic speakers.

Scott Stirm was there. He’s an evangelical missionary from Texas who was one of the most virulent critics of the effort to decriminalize homosexuality in Belize, arguing gay tourists come to the country to corrupt children. He also believes that Haiti made a pact with the devil 200 years ago when it broke the bonds of slavery.

So were Phil Lees, a Canadian who travels the world condemning the evils of Ontario’s comprehensive sex education curriculum, and Theresa Okafor, a Nigerian LGBT opponent, who claims queer and trans advocates are conspiring with Boko Haram.

Philippa Davies, who perpetuates the false belief that homosexuality and peodophilia are linked, provided lessons learned from the fight to maintain homophobic laws in Jamaica.

And Don Feder, who inveighed against Harriet Tubman going on the US $20 bill because “American history was made by white males,” gave a lecture to the mostly black audience about the fast-approaching “demographic winter.”

The World Congress of Families was using the playbook it had perfected in Russia, Nigeria and Uganda, where it is credited with helping pass some of the world’s most vicious anti-gay laws.

The message was clear: unless Christians in the Caribbean draw a line in the sand, their countries would become havens for feminism and gay rights, just like the United States and Canada.

It wasn’t exactly the kind of company Ro-Ann Mohammed, a queer woman, is used to keeping.

Mohammed, a co-founder of Barbados Gays, Lesbians and All-Sexuals Against Discrimination (B-GLAD), one of Barbados’s few LGBT advocacy groups, had snuck into the conference with a handful of other activists.

“It was the worst thing I have ever been to, honestly,” she says. “I couldn’t believe it was happening in this day and age.”

And Mohammed couldn’t shake the sense that history was repeating itself.

“It was mostly the white American men speaking to a crowd of predominantly black Barbadian people and telling them what to do,” she says.

“We have these attitudes that were brought to us through imperialism and colonization. And then there are these people coming from North America telling us that we’re too progressive.”

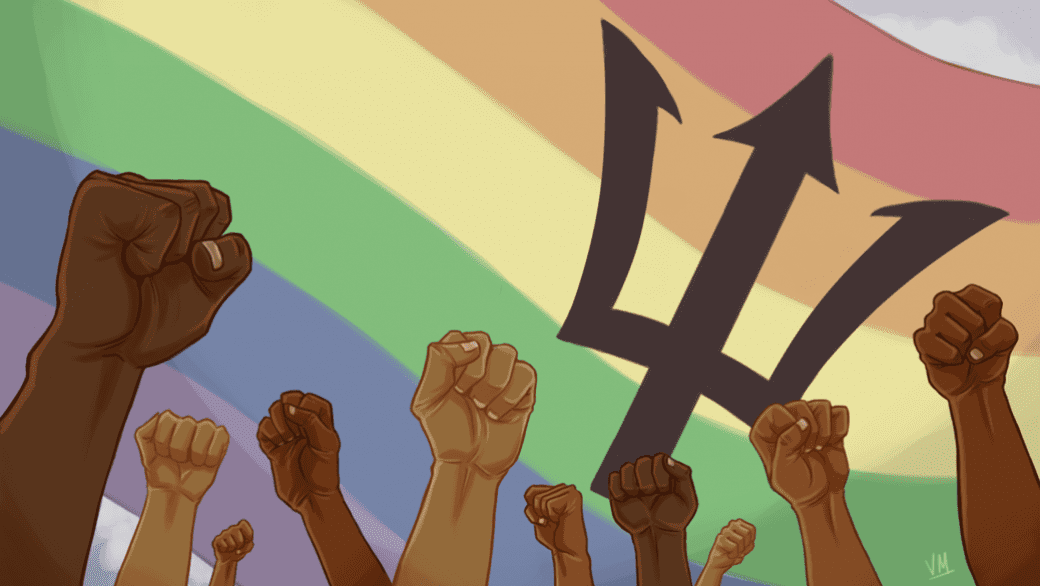

Mohammed grew up in Trinidad, but moved to Barbados to attend university. There, she and Donnya Piggott co-founded B-GLAD in 2011 as a queer students’ organization. When people from outside the university began to join, Mohammed and Piggott realized they could do more good if they expanded to the rest of the island.

Before B-GLAD, the LGBT movement in Barbados was centred around HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, catering mainly to gay men. Queer women, homeless LGBT people and trans youth had especially few options.

“We realized that these people don’t have anywhere to go,” she says. “And people wanted help.”

B-GLAD became a country-wide LGBT advocacy organization and Mohammed decided not to return to Trinidad.

“I found that if nobody else wanted to pick up the mantle in this space, I didn’t see why I wouldn’t be able to do so,” she says.

And now, five years later, she was sitting in a room at a seaside resort, watching influential Bajans lap up homophobic and misogynistic propaganda from wealthy North Americans.

“It was fear-mongering at its best,” she says.

Barbados GLAD/YouTube

About a month after the World Congress of Families conference, the gossip writer for the Nation, Barbados’ leading newspaper, gleefully recounted the public rape and humiliation of an LGBT Bajan.

“She has been a good ‘man’ to many women,” the column began. “Her habits are no secret and she prefers to be referred to as the masculine sex.”

“You see, she had one too many drinks in a farming community recently, and while out cold, a man had his own way with her. He even left the evidence on her body.”

The victim, who hadn’t been seen for days because of the humiliation, had photos of the aftermath of their rape distributed online.

“Some fear ‘my gentleman’ may never be the same after being emasculated,” the writer concluded.

The LGBT community and its allies were horrified and demanded a retraction. The piece was pulled by the paper, which issued an apology to “right thinking members of our community,” but not to the victim.

Though violent hate crimes against queer and trans Bajans are less common than in other parts of the region, harassment, discrimination, property damage, verbal abuse and occasional episodes of violence are a reality for many LGBT people on the island.

And there’s no guarantee that police will help. A recent study showed that 75 percent of LGBT Bajans who went to the police said they were denied assistance.

Sometimes, the police themselves are accused of being the perpetrators.

In September 2016, Raven Gill, a 25-year-old trans woman, complained that she was verbally abused, publicly humiliated and forced to strip in front of male officers after she was arrested for causing a disturbance. Gill claimed that officers repeatedly questioned her gender and placed her in a male holding cell.

Gill, along with René Holder-McClean-Ramirez, a director of Equals Barbados, filed a complaint with Attorney General Adriel Brathwaite, who promised to look into the matter.

According to Holder-McClean-Ramirez, many LGBT people are wary of any interactions with the police.

“You’re not treated as a person reporting a crime,” he says. “There’s always this other layer where you’re guilty of some behaviour, or encouraged what happened to you.”

“And sometimes the same policemen are the persons who are inflicting violence on LGBT persons,” Newton adds.

B-GLAD has hosted multiple sensitivity training sessions with Barbadian police officers. Mohammed says that while she doesn’t think that the police force is resistant to change, there’s still a long way to go.

Discrimination, especially in housing and employment, remains far too common. Mohammed and a former girlfriend were evicted from their home by their landlord for being in a relationship.

“She didn’t want lesbians living in her apartment building, and we had to leave,” she says. “And in Barbados, there’s no way for us to challenge that.”

The lack of recourse is one reason why Barbadian activists have made an anti-discrimination law one of their top priorities.

“It just makes daily social interactions hard if you are a member of the LGBTQ population,” Newton says.

On Nov 6, 2016, hundreds of Christians adorned in the national colours of blue, gold and black held a rally to decry sexual immorality for the second year in a row.

Amid the festivities, which included gospel music and dancers, speakers made the case that LGBT Bajans represented a moral and demographic threat to the soul of the nation.

Johanan Lafeuillee-Doughlin, a local lawyer, said Barbados should not decriminalize gay sex, and begged the crowd to not give into the cultural imperialism of developed countries.

“If all Christian influence on government was suddenly removed, my friend, within a few years no one will have any moral compass or moral absolutes beyond their individual moral sentiments and individual human opinion; that can be so unreliable,” Lafeuillee-Doughlin said, as she shared her view of the “possible social and legal implications of removing the laws which criminalize anal intercourse, otherwise known as the buggery law.”

“We will be inviting a watershed of slippery slopes,” she predicted, as shown in this video. “A secular society void of any moral compass. This is not the nation that Barbadian fore-parents have handed to you and me as Barbadians, and neither should we hand such to generations to follow.”

But despite the nationalistic rhetoric, Americans featured prominently in the night’s proceedings.

Charlene Cothran, a once-prominent LGBT activist and publisher who became ex-gay in 2006, said that no one is born gay, a fact she claimed to be certain of because she had previously chosen to become a lesbian.

“I gave myself fully over to it,” she said. “The lesbian spirit saturated every part of my conscious and subconscious mind.”

Judith Reisman, a conservative activist who claims that homosexual “recruitment techniques” rival those of the US Marines, and that Nazism was a “German homosexual movement,” delivered a powerpoint presentation from the stage.

She went on a conspiratorial rant about Alfred Kinsey, the influential sex researcher, claiming he was a sado-masochistic psychopath, beastiality enthusiast and pedophile, whose work is responsible for many of society’s ills.

“He actually was involved in the sexual torture of 300 to 1,000 infants and children,” Reisman said, matter-of-factly.

She argued that comprehensive sexual education would turn children into “little sexual deviants,” bedeviled by substance abuse, AIDS and venereal disease.

After the event, Steve Blackett, the minister of social work, told a Barbados’ newspaper that he wholeheartedly agreed with Reisman’s presentation.

Barbados must stand firm against the foreign evils and foreign values that threaten the country, he said.

Editor’s note, Aug 16, 2017: A previous version of this story referred to Johanan Lafeuillee-Doughlin as a pastor. She is a lawyer.

Editor’s note, Aug 18, 2017: This story was updated to add a direct quote from Johanan Lafeuillee-Doughlin from her speech to the rally as seen in this video.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra