Even though Pride Toronto’s (PT) censorship decision provoked an onslaught of outrage on Twitter and Facebook over the past three months, the organization’s strategy seemed to be to ignore the criticism and, in some cases, dismiss the work done online by queer activists.

Several Xtra.ca articles on the PT censorship issue drew more than 100 comments each, breaking records for most-discussed stories ever on the site. Facebook was the top traffic source to Xtra.ca’s coverage, as many shared articles through their profiles and with free expression activist groups.

On Twitter, between March and June more than 5,000 tweets bore the #PrideTO hashtag — a keyword used to track discussion about PT.

“Social media really does create avenues for people to hold organizations to account,” says activist Rick Telfer. He created the Don’t Sanitize Pride Facebook group after PT announced in March that it would require all parade participants to have their signs vetted by what it called an ethics committee.

Facebook and Twitter allow activists to create an audience for their message, says Telfer. “It was always possible to create an audience through email lists and groups. The very setup of Facebook — the ease, the user-friendliness, its popularity — that’s what makes it work.”

Telfer’s Facebook group grew quickly, topping out at around 1,900 members. “Every time Pride Toronto did something stupid, we would gain another 200 to 300 people,” he says.

Two weeks after announcing its sign-vetting policy, PT announced that it was backing down. The reversal seemed to suggest that PT was listening to community feedback, but the organization clearly still intended to censor Queers Against Israeli Apartheid (QuAIA).

QuAIA, meanwhile, used Twitter effectively to share information and provide counter-spin to PT’s press releases.

Social media “is democratizing access to media,” says QuAIA member Corvin Russell.

With Facebook and Twitter, says Russell, “you’re able to use your existing social networks to communicate a political message. In the case of the queer community, you can actually reach large sections of the community without going through mainstream media at all.”

Russell suggests that PT, an organization with established links to traditional media, does not have a social media advantage over queer activist groups. Social media “really allows you to bypass the gatekeepers” and get a message heard, he adds.

As community members protested outside PT headquarters in May and June, and as many voiced their outrage on Twitter using the #PrideTO hashtag, PT’s social media strategy appeared to be to ignore all criticism. During each protest, PT tweeted a link to a press release on its webpage before continuing to tweet and retweet its featured “artist of the day” and other positive comments about Pride. But criticism was overwhelming, and PT’s strategy failed.

PT declined to speak to Xtra for this story, but executive director Tracey Sandilands remarked elsewhere on the role social media played.

In a June 9 letter to InterPride, an international association of Pride organizations, Sandilands wrote that Xtra, “coupled with the prolific use of social media that enables everyone to weigh in, is driving the campaign against PT’s decision to censor QuAIA.

“No matter how vocal they are, the number of people involved constitutes at best less than one percent of the community that attends Pride,” added Sandilands.

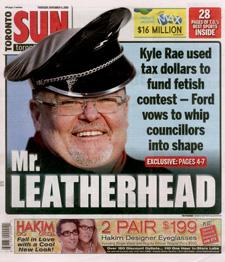

And in an April email to Toronto city councillor Kyle Rae, Sandilands dismissed members of Telfer’s free expression Facebook group as the “howling left.” She wrote that PT would be mostly ignoring them.

The problem with Sandilands’ comments, suggests Telfer, is that they are “not just insulting to the people who created that group, but they’re also insulting to people who are members of it. It implies that they’re not free-thinking individuals. It implies they’re just lemmings.

“Everyone can create a message and everyone can create a forum for that message, but not everyone does and not everyone is capable of persuading people to engage,” says Telfer.

Russell says Sandilands’ June 9 letter suggests “she has a problem” with the open forum inherent in social media.

PT’s June 23 decision to rescind the ban suggests that it finally listened to the feedback its constituents were giving it via social media, but while doing so, PT once again downplayed the role of community outrage. In a press release, PT credited a proposal from so-called “community leaders” for its decision to back down.

“One thing this experience has shown us is that having a PR firm doesn’t necessarily work to your advantage,” says Russell, referring to PT’s conservative PR firm Navigator, which advised it to “hold steady,” that the “majority of people will ignore both sides.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra