After 43 years with Pink Triangle Press, Ken Popert is stepping down as executive director.

Popert will leave his position in March 2017. Gerald Hannon, a member of PTP’s board of directors, says that the board has started searching for the organization’s next executive director.

Popert’s involvement with the Press goes back to 1973, when he began contributing to The Body Politic. He remained a member of the collective that ran the magazine and was appointed interim publisher in 1986. He has remained at the helm of PTP (which publishes Daily Xtra) ever since.

But Popert, now 69, says that the time has come to move on.

“We’ve been engaged in this strategic process for the last couple of years and I think it’s going to renew the organization,” Popert says. “It’s been on my mind for some time how much longer I will work here, so it seems like an opportunity to leave on a high note.”

During his time with the organization, PTP has gone through a number of radical transformations. It all began when The Body Politic, a radical gay and lesbian magazine with international reach, was launched in 1971. Throughout the ’70s, the ever-provocative publication was one of the touchstones of queer life in Toronto. It eventually folded in 1986, but PTP lived on through Xtra, a community newspaper that launched in 1984.

Xtra expanded into Vancouver and Ottawa in the 1990s, buoyed by Cruiseline, a gay telephone personals service owned and operated by PTP. In 1998, PTP launched Squirt, an online dating and hook-up service for gay men. Cruiseline was sold in 2011, and in 2015, PTP ended print distribution of Xtra in its three markets, becoming an online journalism enterprise.

Popert was there throughout the Press’s various incarnations.

“What I’m very pleased about is our ability to keep changing and growing,” he says. “Although it started as a group of very impractical idealists, our organization has shown quite an unusual ability to stop doing things that aren’t useful anymore and start doing something new.”

And in his four decades with PTP, Popert has also made a number of contributions to both the fight for sexual liberation and press freedom in Canada.

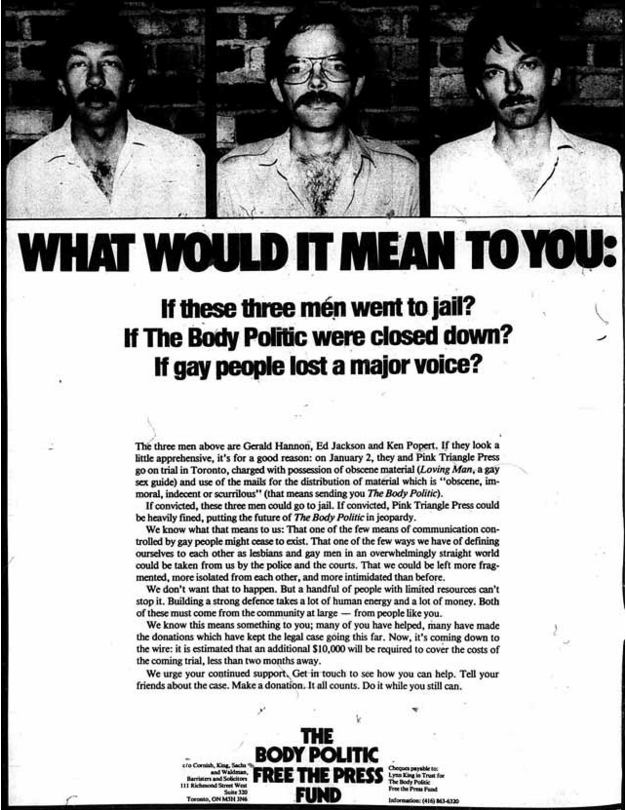

After the publication of “Men Loving Boys Loving Men” in The Body Politic in 1977, police raided the Press’s offices and Popert was one of three people charged with publishing obscene materials. The trial became a rallying point for the queer community. Although a judge acquitted all three men in 1979, the attorney general appealed. PTP went on to win that case as well in 1983.

“I think our trials were very important in making freedom of expression an issue in Canadian political culture because it was not for most of the history of Canada,” Popert says.

In 1981, when Toronto Police conducted simultaneous raids on four bathhouses in the city, members of the gay community met in the offices of the The Body Politic to figure out a response. Popert was one of the people arguing that people should protest immediately. That was the view that won the day and eventually led to mass protests in the streets of Toronto. Later that year, he was struck by a police cruiser when a peaceful protest against the police turned into a riot.

“As a result of my previous experience at Cornell, because of the prominence of the anti-war movement on that campus and the events that happened there, I’d already seen one sort of mass uprising involving thousands of people,” Popert says. “I feel like I’ve been very lucky in my life to have seen two such big shifts of masses of people in their behaviour and their opinions.”

In 1993, Popert’s partner, Brian Mossop, fought all the way to the Supreme Court for bereavement rights related to the death of Popert’s father. He argued that the government should recognize the couple as a family unit, though not necessarily married. Although unsuccessful, it was the first gay rights case ever heard by Canada’s highest court.

But his role at the head of PTP was the consuming professional passion of his life.

When he was appointed interim publisher in 1986, the Press was in dire financial straits.

“We had financial crises before, but they never had any long-term effect,” he says. “But this time, it was clear that people were just worn out. The sense of emergency that had held the paper together was unraveling.”

Popert recommended that The Body Politic be shut down and that Xtra, which had a younger, Toronto-centric readership, become the primary concern of the organization. The collective agreed, and The Body Politic had its last issue in 1987.

Profits from Cruiseline, launched by Colin Brownlee, who Popert describes as “one of the many saviours of the Press,” allowed Xtra to expand into Vancouver and Ottawa in the ’90s.

“I don’t care if all Xtra does in Ottawa is blow down the street, I want it blowing around the feet of Supreme Court justices as they step out of their cars,” Popert recalls saying about the expansion. “I felt like we had to look like we were speaking for more than just parochial Toronto interests.”

Popert continued to focus on the media side of the organization, while Brownlee managed Cruiseline.

“I always preferred to leave the business to people I felt were more competent than I was to run it,” Popert says.

With the arrival of the internet, PTP launched Squirt in 1998, which would in the coming decade eventually replace Cruiseline as the primary revenue source for the Press.

A strategic review of the organization was launched in 2013, and in 2015, the print editions of Xtra were shut down and the journalism went online only.

“Print was not the backbone of the organization,” Popert says. “The journalism was the backbone of the organization, and our interest in activism and social change.”

Looking back, Popert says that he’s proud of the Press’s many legal fights, its role in the uprising following Operation Soap and the course it set during the AIDS epidemic.

“I think in fact, to some extent, the city we see around us is a product of the existence of our organization,” he says.

For the future, Popert hopes that PTP will continue its commitment to sexual liberation.

“There has to be somebody who speaks with a logical and clear voice about sexual issues,” he says. “So there’s still a very big piece of work there that somebody’s got to do. And it can’t be just us alone, but I would hope that the Press would continue to be a voice for a logical discussion of sexuality.”

When asked why he never decided to leave the Press anytime during the past four decades, Popert’s answer is simple.

“There was nothing else that was so interesting to me,” he says.

For more information on the position of executive director and how to apply:

dailyxtra.com/work-

Editor’s note, Aug 4, 2016: This article was amended to clearly disclose that Pink Triangle Press publishes Daily Xtra, and to correct the sub-headline to reflect Ken Popert’s tenure of more than four decades.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra