What does it feel like to be an afterthought?

While Toronto is arguably one of the most multicultural centres in the world, artists of colour can sometimes be made to feel like their presence at performance venues around the city is a gesture of liberal white guilt, rather than a genuine affirmation of their talents. Given the same opportunities as a white artist, a racialized artist might be held to a different standard or simply disregarded as being the token brown person at an event.

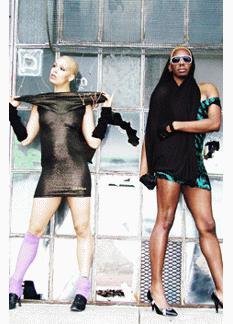

When Milo de Milo (aka Milo Ramirez) founded Colour Me Dragg in 2006, he sought to create a space where queer artists of colour could be judged solely on their talents, without having to wonder if they were being included as part of a quota.

“It was becoming obvious to me that most spaces were predominantly white and were not necessarily safe for people of colour,” Ramirez says. “A lot of us didn’t feel like we had access to those spaces or feel comfortable approaching those producers. I wanted to make a space where we could support each other and feel safe in that way.”

Since its inception the collective has grown to include Dainty Smith, Chase Tam and Tricia Hagoriles, creating a fearsome foursome united by a common set of experiences.

“I hate feeling like I am being included in something because of well-meaning guilt or exoticism,” Smith says. “I carry with me the experience of being told that I’m not worthy and that I don’t have a place in the world, let alone on a particular stage. It’s not only hurtful but also deeply insulting.”

“When tokenism is in play, it’s very hard to get around it,” Tam adds. “In other venues I often felt like the token person of colour, regardless of my skill level or the quality of my work. There are certainly people in the queer community who think racism is obsolete, but to me that’s like saying homophobia is obsolete.”

While it was founded primarily as a venue for drag performers, events now feature dance, burlesque, spoken word, live music and video art. Programs typically include 20 to 30 artists and are curated through open calls. The collective aims to create the most diverse space possible, giving all artists the chance to perform as long as they identify as a queer person of colour. The constantly fluctuating lineup means no two events are the same.

“It ends up being a kind of magical experience each time because you have all these performers who wouldn’t normally share the stage,” Hagoriles says. “We keep the space open for all types of performers, but we also put a lot of thought into how we arrange the program so that everything stands out. It’s actually not that hard, since everything is so different.”

“I’ve had performers come up to me and say that we’re the only stage where they perform,” Tam adds. “It’s great to hear that we’re giving these artists opportunities, but it’s also really sad to be reminded that they don’t feel like they have the right to perform in other venues.”

The group sees themselves as having a greater responsibility than just providing a place for people to strut their stuff. A portion of the proceeds from each show goes to a specific community organization. Past recipients include Blackness Yes!, QuAIA and the Asian Arts Freedom School. They’ve also donated to international organizations in Kenya and Uganda that provide services for trans people, including binders and hormone injections. Proceeds from their Pride performances this year will go to the Transformative Justice Learning to Action Group, an organization dedicated to creating safer communities without the use of the criminal justice system.

“It was important to us to be able to use the success we’ve had to support other platforms that feed the community,” Hagoriles says. “Our shows typically sell out, so we’ve been able to donate thousands of dollars over the last few years to different groups. Even smaller amounts of money can make a huge difference to these organizations.”

The group was excited to learn they’d be headlining Buddies’ Queer Pride festival for the second year in a row.

“We’ve had five years of people doubting us or not taking us seriously, so it’s amazing to be at Buddies and be treated like a big show,” Hagoriles says. “That demonstration of confidence means so much. We’re not just a quota or token people of colour. We’re a force to be reckoned with.”

“Even after five years, I still have people asking me why this company is important,” Ramirez adds. “These sorts of conversations make me realize just how unaware some people are of the racism that exists in the queer and trans communities. It reminds me over and over just how important this group actually is.”

Find Colour Me Dragg at Pride Toronto’s Trans Stage (and at the afterparty at the Gladstone Hotel) on Friday, July 1; at the Village Stage on Saturday, July 2 at 6pm; and on the Blockorama stage Sunday, July 3.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra