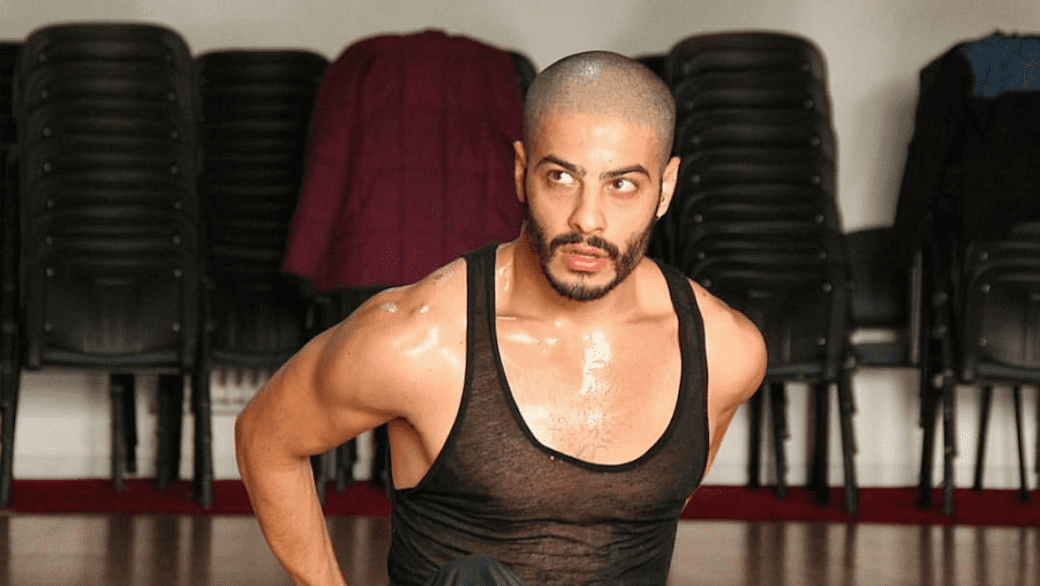

“In the beginning, it wasn’t easy for me,” Ayman Safiah says. “I was the first male from my village who made this announcement. I struggled with whether I should be the same as other people but I realized this is who I have to be. This is my dream.”

You might think Safiah is describing coming out as gay. Raised in the small primarily Palestinian village of Kfar Yasif in the north of Israel, his environment wasn’t a place where it was easy to be queer. But in this case, he’s actually talking about his other coming out; his declaration to the world he wanted to dance.

“People saw it as unmanly, as feminine,” he says. “But more than that is was also un-Palestinian, something outside the culture. When you do something new you’ll always be questioned because it’s strange to people. Being different is always a challenge. But so is hiding yourself from the world and not being honest about who you are.”

Safiah appears in Badke, a show created by three Belgian choreographers and 10 Palestinian performers from a diverse range of movement traditions including hip-hop, circus, folk dance, and capoeira. The title is a play on “dabke”; a social folk dance common throughout Palestine, Jordan and Syria. Often performed at weddings or other celebrations, here it’s reinterpreted, blending other styles and pop cultural elements to explore the twin Palestinian desires to belong in their homeland and be part of the world beyond.

Safiah’s first real taste of the world beyond came at 16, when he received a scholarship to study at London’s Rambert School. Along with helping him develop his passion, he credits the move with his ability to come out.

“In London, I didn’t have to think about where I went out, what I said or how I dressed,” he says. “At home, I wasn’t brave enough to be myself. But going abroad gave me the strength to do that. It was much easier in that way. At the same time, my roots are important to me and I don’t want to forget the process that led me to be who I am. Where I come from means everything to me.”

After completing his studies, he joined the Rambert Dance Company, and performed in a number of big musicals. He stuck around London for a few years, but had to head back to Palestine after some visa complications. Initially he was nervous to return, partially because it meant less sexual freedom, but more so because he was leaving one of the world’s great performance capitals for a place with far less opportunity. But on returning, he found things had begun to shift creatively.

“People back home were mostly occupied more practical matters like borders, rights and education,” he says. “There wasn’t a focus on the arts in the same way there as in London. But the dance field has been growing a lot and Ramallah now has one of the largest dance festivals in the region. And the friends who decided to leave me when I became a dancer, it’s been amazing to see how welcoming they are now that I’m back.”

He’s since found no shortage of work, collaborating with companies at home and abroad as well as teaching at different schools. While the dance community has seen major shifts since he first left, cultural acceptance of homosexuality has been slower.

“Being gay isn’t easy anywhere,” he says. “You’re always questioned and looked at as different somehow because people say it’s out of nature. Before, I used to get very angry when people talked to me like that. Now I’m able to look at the individual person, his background, where he lived and what conditions he had that made him think that way.”

At the same time he’s helping develop the dance scene back home, he’s working toward both greater cultural acceptance of homosexuality there and a greater understanding of what it means to be Palestinian abroad.

“I want to change how the world looks at us,” he says. “And as a company we’re aiming for that with this show. Going anywhere and having to hide who you are isn’t a weight you want to carry, whether it’s about your sexuality or your cultural identity. You should follow your instincts and find what you love. The world will become a better place when we start to accept each other as human beings.”

(Badke

Wednesday, Feb 17–Saturday, Feb 20, 2016

Fleck Dance Theatre, 207 Queens Quay W, Toronto

harbourfrontcentre.com/worldstage)

(Main story photo by Sama’a Wakim.)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra