I happened to watch Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura—a visually stunning 1960s film about bourgeois ennui—for the first time during the same week that I read Mike Fu’s new novel, Masquerade. At the time, I didn’t realize that the film provides a key of sorts to Fu’s tale of queer diasporic uncertainty. In L’Avventura, a group of wealthy friends takes a yachting trip near Sicily; when one of them disappears without a trace, her lover and her best friend are only briefly affected. Unable to feel the loss in any significant way, they turn to each other for a rather passionless, passive affair, against a backdrop of lavish yet boring parties. In Masquerade, Meadow Liu, a thirty-one-year-old queer bartender who lives in New York and travels frequently to Shanghai, where his parents live, is similarly unmoored. Though he himself isn’t wealthy, he drifts along with an international art crowd, which he accesses through his friendship with the chameleonic Selma Shimizu, a beautiful, wealthy artist whose shifting personas fascinate Meadow. The novel unfurls over the course of a summer, during which Meadow is led into a mystery that might provide him with some much-needed self-understanding.

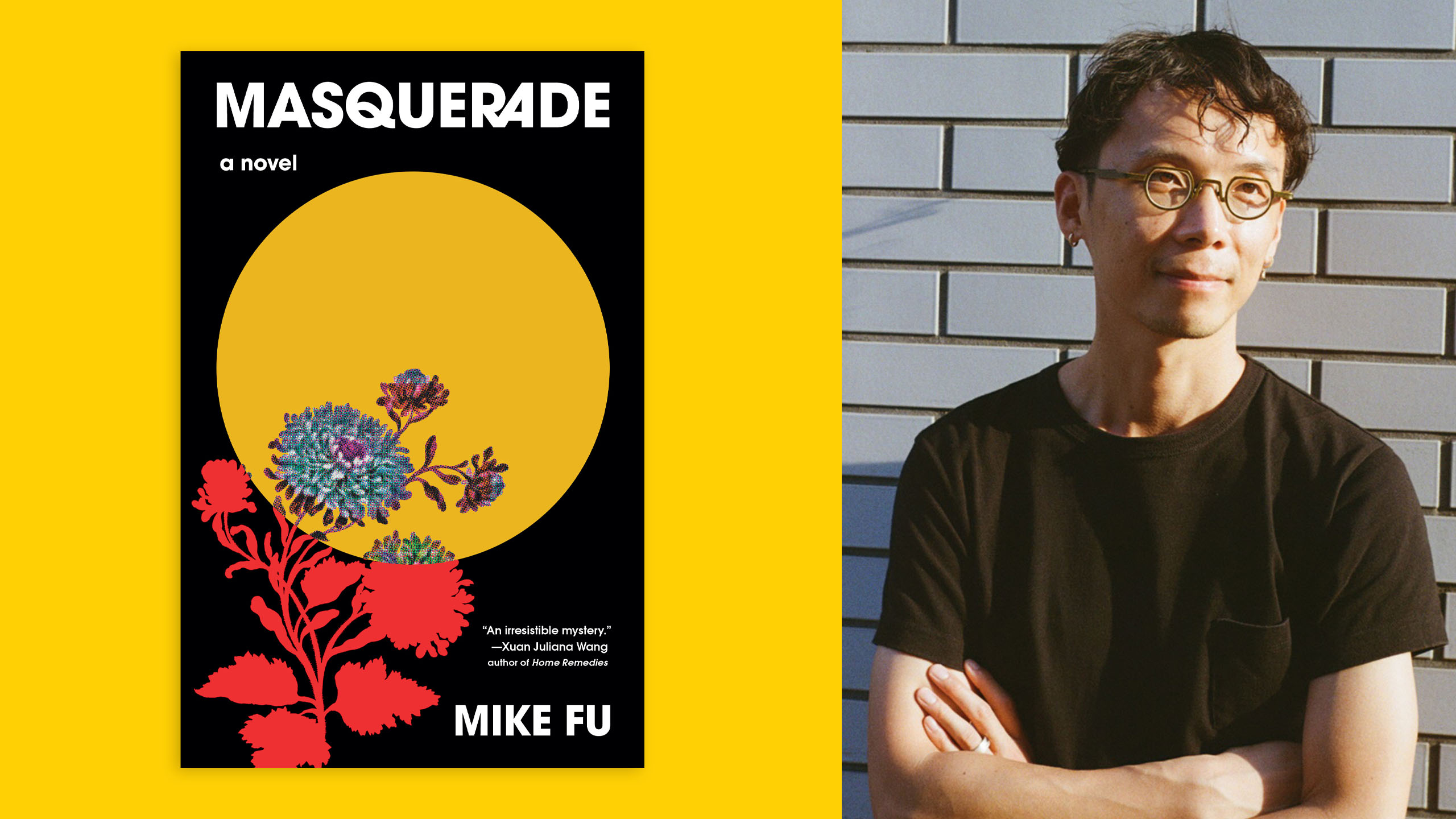

Mike Fu is a Tokyo-based writer, translator and editor. In 2020, he published a Chinese-to-English translation of Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao, the late Taiwanese travel writer who became a feminist icon of the 1970s and ’80s. Masquerade is Fu’s first novel, and it probes some compelling questions about moving between worlds, hedonism, melancholy, bourgeois disconnect and diasporic duality. Meadow, having dropped out of a prestigious PhD program some years ago because he didn’t feel compelled by academia, works at a bar, house-sits for the glamorous Selma and repeatedly tries to find love with various men, to no avail. His latest romance, with the sweet and energetic Diego, whom he was hopeful and excited about, ends with Meadow being ghosted a month in. He laments this to various friends as he dines and drinks with them at a slew of trendy restaurants and bars, in both Shanghai and New York. His heartache is interrupted by a mysterious book he discovers in Selma’s apartment, titled The Masquerade. It’s an English translation of a Chinese text, written by someone who seems to share Meadow’s Chinese name: Liu Tian (it is impossible to tell for sure, because of the ambiguities of romanization). The story takes place in late-1930s Shanghai, after the Battle of Shanghai, part of the Second Sino-Japanese War. It depicts an opulent masquerade party, dripping with excess, where the ills of the outside world are largely ignored in favour of pleasure. This other Liu Tian writes: “It is only human nature to seek pleasure and diversion. Some may even choose to ignore the violence or, worse yet, rationalize it for the greater good, deluding themselves to believe that a measure of cruelty is necessary to wrest control of collective destiny.” This portentous passage would seem to hint that Meadow’s trajectory will involve wrestling with his own demons, and the demons of the art party scene he is part of, but the novel never fully steps into violence and cruelty, or pleasure and hedonism enough for this kind of tension or resolution to occur.

Meadow is a gentle lost soul who drifts through life, letting other people pull him in various directions. His inability to maintain a longer-term relationship is part of a larger sense of malaise that he’s felt for years. “There were so many ways to exist in the world and exactly none of them seemed to be right,” he laments. Much of this lost feeling comes from his constant travel between China and the U.S. Meadow doesn’t feel grounded in either country. While “China is a topsy-turvy place he could never claim, and yet to which he is inextricably bound,” he is listless and ambitionless in New York, where he spends the majority of his time. He relies on the enterprising energies of his friends in order to take part in the world—Selma invites him to fancy dinner parties and art openings, while his friend Bobby, also queer and Asian, is his party-boy wingman, always bringing him out to bars and clubs, always game, always encouraging. When Selma suddenly disappears from a residency in Shanghai, I expected Meadow’s inner life to come into clearer focus—surely he would be worried, stressed out, perhaps this disappearance would spur some conflict in his life, perhaps it would be a catalyst for action on his part. But nothing of the kind happens—Selma is such an enigmatic character, both to Meadow and to the reader, switching so quickly in and out of roles, outfits and attitudes, that we can’t grasp her, and therefore can’t really understand what her absence means in Meadow’s life.

In a flashback to an indulgent weekend spent at a cottage with Selma and another friend, Meadow remembers watching L’Avventura while on shrooms. It clicked for me that Fu’s Masquerade is less a story about the emotional ties between Meadow and his now-missing friend Selma, or about Meadow’s heartbreak at being ghosted by Diego, and more about the shallowness of emotion that can result when people’s lives are built around aesthetic pleasure, and little else. Liu regularly describes the delicious meals eaten by his characters, or lists the books found in their bookshelves or the albums they listen to. But, since the characters rarely have any thoughts about or reactions to these experiences of food or art, these lists don’t tell us anything about their inner lives—they merely allow us to picture the spaces these people move through, and the gestures they happen to make (picking up a glass, spearing broccoli with a fork), almost like watching security footage. Toward the end of the book, Meadow does have an epiphany about his own passive approach to life, which he arrives at thanks to The Masquerade; however, because it’s taken so long for this to occur, the novel has lost much of its tension by this point.

There are scenes in the book that vibrate with life, and these are mainly scenes in which Meadow briefly allows passion to take him over, usually with a lover. Here, Fu’s writing takes on an electric energy. One lover’s skin is “taut and hot to the touch, his musk tinged with a trace of tobacco, a hint of lime and juniper on his lips.” During a hookup, “the shadows of tree branches trembling in a night breeze danced on the wall next to them, the pale shards of light between their snaking boughs winking like fragments of a dream.” As Meadow is falling for Diego, he can’t control his emotions: “How delicious and thrilling the descent was, the body tumbling head over heels, metallic momentum in his belly, so much air blasting upward into his mouth that he couldn’t even scream.”

I found myself wishing for more moments like these—when Meadow is caught up in stronger emotions than listlessness and uncertainty. Meadow is clearly conflict-avoidant, but sometimes it feels like the novel itself is as well—there are essentially no interpersonal confrontations in it. Whenever it seems that conflict could rear its head, characters instead tend to abruptly disappear, leave town or simply fade away. Bobby, to his credit, is the one character who drags Meadow with great accuracy, telling him that he’s like elastic-waist pants: “You fit so many kinds of people that it’s easy for you to lose your own shape. That’s your tragic flaw.” Had Bobby stuck around longer, he could have provided Meadow with some much needed real-talk—maybe they could even have had a fight. Unfortunately, after an exciting turn of events between the two friends, Bobby up and moves away to the West Coast.

There’s nothing wrong with a novel (or a film) focusing on a character who’s adrift, of course; “plotless novel” has become a common way to describe the micro-genre of fiction that is more about self-reflection and less about external action. It’s just that in the case of Masquerade, we know fairly little about Meadow’s inner turmoil, since much of the text is dedicated to describing the appearance of objects and people around him, rather than his interiority. He’s a character who knows he is missing something, but doesn’t know what it is; his yearning is obscure to the reader, because it is obscure to him. The novel itself doesn’t quite seem to know what Meadow desires, either, and so we remain stuck with him in “nowhere-space”—which is how Meadow describes transpacific airplane travel. He wonders if he has lost something of himself about the ocean, if that is why “his life still feels lousy and incomplete,” but this question isn’t ever really explored further.

There’s much to appreciate in Masquerade too, despite its meandering quality: Fu writes a revolving door of people around Meadow—people who appear and disappear at various spots in New York and Shanghai, whom we meet briefly and never show up again. I like nothing more than a well-populated novel, especially a queer one, because of the way it pushes against more heteronormative character-driven books in which the protagonist often has one love interest, and one friend and nobody else around. Fu’s refusal to write a more predictable “diaspora novel” is also laudable: Meadow’s story is one of in-betweenness that results not from a one-way migration, but from moving constantly back and forth between China and the U.S. Once he begins to read The Masquerade, some intriguing parallels are drawn but not fully teased out between the wartime opulence of certain social strata in 1930s Shanghai, and the frivolous partying of hip queers and artists in 2010s New York. This is a first novel full of promise, that may have gotten a little mired in its own themes—uncertainty, passivity, indecisiveness.

Midway through the book, Fu best describes Meadow’s angst: “He yearned to give shape to his existential desires, explain in words what the pulsing, vital mass within him was driving at.” By the end of the novel, Meadow is finally heading in the direction of clarifying his desires and drives—hopefully Fu will write more books, and explore many of his ideas further.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra