Curt Allison never thought he’d witness the election of an openly gay church leader in his lifetime.

“I don’t even know that I had the foresight to wish for something like that,” says Allison, who grew up in a Pentecostal community in the American South. “For me, just being accepted by my local congregation would be a big thing. I wondered if that would ever happen. But I never thought an openly gay elected leader would be elected to head the United Church.”

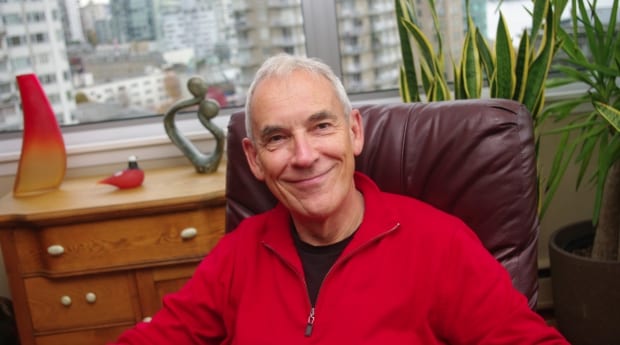

Allison has been working with Gary Paterson for the last decade. Paterson made history in 2012 when he was elected to the highest position of the United Church of Canada, becoming the first openly gay leader of a major Christian denomination in the world.

Brent Hawkes, the senior pastor of the queer-friendly Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto, sees Paterson’s election as church moderator as a “phenomenal” symbol of progress.

Asked how he, as a gay minister, got elected to the highest position of the United Church of Canada, Paterson pauses. The church members moved from inclusion to full celebration, he says.

“We moved to that place of affirming and celebrating and saying, ‘there’s an incredible gift that gay and lesbian people bring,’” says Paterson, who completed his three-year term as moderator in August 2015. “It’s not just, ‘we will include you’ but ‘wow, are we ever lucky because you are part of the body and your particular gifts enrich us.’”

Paterson points out that the United Church of Canada was already well on its way to full acceptance and celebration of gay and lesbian people by 2012, on the eve of his election.

In 1988 the church became one of the first denominations of Christianity to extend full membership, including ordination, to openly gay and lesbian people. In 1992 Paterson’s husband, Tim Stevenson, became its first openly gay minister.

“This was almost like the final step in that whole journey,” Paterson says. “You can almost plot from the decision made in 1988, through the next several years and decades, the growing comfort with the inclusion of gay and lesbian people in all areas of church life.”

“It really raises the bar for other denominations,” Hawkes says.

“In all the other denominations, there are activists who have been working for decades to move their denominations along, and that’s hard work,” Hawkes notes. “When you see progress in other denominations it encourages the activists to keep fighting in their own denomination.”

Paterson says he occasionally gets discouraged when he considers the small percentage of Christian churches worldwide that support gay and lesbian people.

“The bad news story for me is that the United Church is small,” he says. “We’re the largest Protestant denomination in Canada but that’s still only 400,000 or 500,000 people. There are 2.2 billion Christians in the world and the vast majority have not reached a place of acceptance or inclusion.”

Paterson says church partners in Africa who traditionally invite the moderator to visit advised him that the presence of an openly gay church leader would be counterproductive.

“The African partners said ‘don’t come.’ And I said, ‘Look, I’m not here with an axe to grind about gay and lesbian issues. I’m about so much more.’

“They said, ‘We understand that, but because you are so open any reporter will know this and will ask about it and that will become the story, and therefore it would be counterproductive because you will be seen as a white colonialist coming in and implicitly, at least, telling us how to run our church life.

“‘Secondly,” Paterson says he was advised, “if you have private meetings, gay and lesbians or even just gay- and lesbian-positive organizations, they will be in danger once you leave, so you could actually be bringing trouble on allies.’”

Still, Paterson says he has witnessed “seeds of change” within partner churches in Latin America who invited him and Stevenson to not only attend their congregations but to deliver workshops on how the United Church became an inclusive community.

He believes his being moderator helped enable some change in some partner churches and “helped move forward their journey.”

He remembers one group of Baptists “who came up to the seminary to hear the presentation that Tim and I made. And one Baptist guy in his 70s said, ‘Moderator, you talked about it taking 25 years according to change theory for an institution to change. I won’t live to see my church change but I have witnessed the first step.’ That was quite moving.”

Allison sees Paterson’s legacy as a symbol of hope for LGBT Christians who may feel alienated or hurt by their church.

“I think his reputation, election and what he’s all about is a way of saying, ‘No, not all church is like that — some churches are welcoming and if you’re yearning for that and miss that community, there is a place for you.’

“That’s the message of hope and light that he shines,” Allison says.

With Paterson’s three-year term coming to an end, the membership of the United Church of Canada elected a new moderator on Aug 14, 2015 — a lesbian. Jordan Cantwell now becomes the first openly lesbian moderator of the church.

Cantwell will oversee the church’s “living apology” to LGBT people, which will take the form of a travelling interactive art installation over the next three years.

As for Paterson, he plans to resume his role as lead minister at St Andrews-Wesley United Church in Vancouver in December.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra