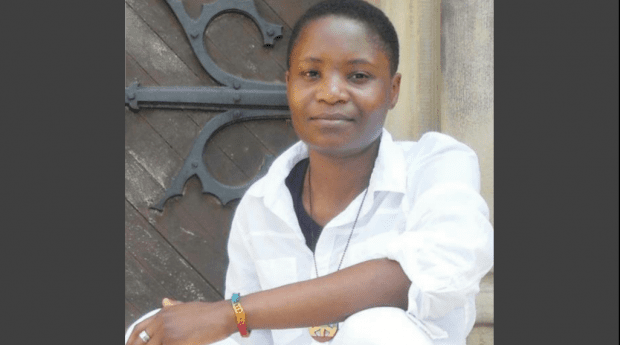

Val Kalende has had a precarious few years. The Ugandan journalist and activist, a self-described spiritually grounded “preacher’s kid”, has been back and forth between Uganda, the United States and Canada seeking political asylum.

After a journey spanning more than four years and two continents, Kalende, who uses the pronoun they, has at last found a home in Toronto. On Sept 8, 2015, they won asylum in Canada after a two-month process before the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB).

But if this weren’t enough, Kalende did it all under repeated threats of rape and a televised call for their hanging in Uganda. That’s because Kalende is a public figure in the Ugandan LGBT rights movement and identifies as genderqueer.

“These past two months I’ve been dealing with trauma healing,” Kalende tells Daily Xtra. “Since I’ve come to Canada I’ve had time to off-load most of that baggage. When I was in Uganda, there was no time for self-care. You just didn’t think about it. It was all about survival.”

It wasn’t always that way. Kalende once enjoyed a career in journalism as a features writer at Daily Monitor, one of Uganda’s leading independent newspapers. Some of their articles on human rights issues, entertainment and education are still available on the paper’s website.

Yet in October 2007, Kalende chose to leave the paper to focus on LGBT rights activism.

“It was a bolder step to be who I am, to express myself, to contribute to the building of the movement,” Kalende says. “But of course it was sad to leave that work, because I enjoyed my job.”

Kalende put their journalistic skills to use, conducting community-based research into the needs of LGBT people in Uganda through organizations including Freedom and Roam Uganda, and Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG).

It was rewarding work, but difficult. In a country rife with homophobic politicking from the Ugandan ruling class, and where Western evangelical cohorts like Scott Lively preach, Kalende says that “not knowing if you’re going to live another day” was a constant, and very real, fear.

“I grew up in the church,” Kalende explains. “Once I started to feel that the church wasn’t a safe space for me, I lost that sense of belonging, of self. If I can’t be a part of my community, which is the LGBTI community, and if I don’t have that spiritual attachment, I don’t know who I am anymore. It’s actually one of the biggest reasons why I decided to make a claim for political asylum.”

In 2010, Kalende began four years of travel between Uganda and the United States, attending human rights conferences and speaking engagements. But it was not until the passing of Uganda’s infamous Anti-Homosexuality Act in February 2014 that Kalende considered leaving their homeland for good.

“I didn’t want to leave. There was something inside of me that kept thinking, things are going to get better. Then the anti-homosexuality bill was passed into law and I saw most of my friends leave Uganda. I think that is when it started to sink in that Uganda is not a place for me anymore.”

After a frustrating year trying to claim asylum in the United States — with no prospect for employment or education during the claim period — Kalende decided to apply in Canada. Kalende says the Metropolitan Community Church and Access Alliance helped connect them to a lawyer who filed Kalende’s claim for political asylum. A decision of the IRB’s Refugee Protection Division found Kalende to be a convention refugee on Sept 8.

Kalende says that the Canadian refugee system has treated them well, but acknowledges that being a public figure and having extensive personal documentation has helped their case.

“Most of us leave Africa without any knowledge of what organizations we should reach out to when we arrive,” Kalende says. “We need to have local organizations in Africa that have that information. Most [asylum seekers] have very high expectations of the system, and they come here and get so frustrated. If you come here without a well-documented story, it’s going to take you long.”

Kalende identifies some problems with the Canadian system, including a filing period that is too short for asylum claims and reductions to social benefits for refugees. They also believe that Canada needs to open its borders to more refugees — especially now.

“I think [the immigration system] assumes that political asylum, or the rights of refugees, are a privilege,” they say. “I don’t think that is a privilege. I think it is a basic right. It is that sense of belonging upon which basic rights are predicated.”

Now settled in Toronto, Kalende has already joined social and community groups including the recently launched Dignity Initiative, a network of organizations that aims to advance best practices in international LGBT solidarity work. Kalende has also found a welcoming place at The 519’s regular Sunset Service, an inclusive inter-spiritual space for marginalized communities.

“Thankfully,” Kalende says, “I have my chosen family.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra