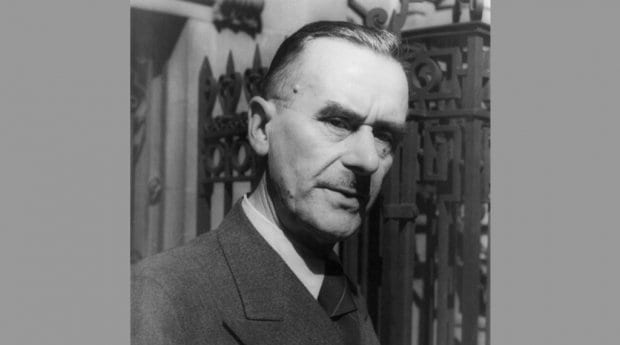

Thomas Mann in 1937. Credit: Library of Congress; public domain

View of Lübeck, with Holstentor on the right. Credit: Arne List

Horror buffs may recognize this row of former salt warehouses as the onscreen home of Nosferatu in gay filmmaker FW Murnau’s 1922 film. Credit: Arne List

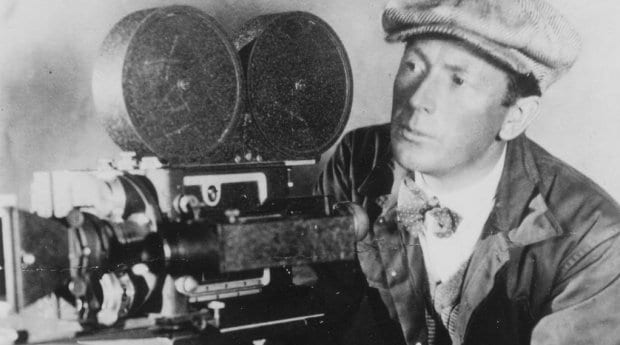

Gay filmmaker FW Murnau. Credit: Photographer unknown; public domain

Max Schreck as Nosferatu (1922). Credit: Nosferatu, 1922

A popular tourist stop is Buddenbrooks House, once home to Thomas Mann’s grandparents, today a small but informative museum devoted to the Mann’s cultural impact and broader role in the Hanseatic region. Credit: Christian Baines

Lübeck’s real charm lies in its medieval architecture. Visitors are greeted by the Holstentor, a symbol of Lübeck’s dating back to 1464. Credit: Christian Baines

Another view of the salt houses in Lübeck. Credit: Christian Baines

International visitors often bypass northern Germany. Those that do swing by won’t often get past the obligatory couple of days in Hamburg, missing a very special German city with a beautiful medieval core, and a rich literary history.

Lübeck, for its modest size, leaves a big footprint on German culture, history, politics and literature. In addition to being the former capital of the expansive Hanseatic League, Lübeck has produced three Nobel Laureates: politician and human rights activist Willy Brandt; and authors Günter Grass and Thomas Mann.

It’s Mann’s legacy that makes Lübeck a worthy stop for LGBT visitors. The writer’s sexuality could never be categorised as straight, but his apparently internalised homophobia has been the subject of fierce debate in recent decades. The son of Lübeck’s richest man during an age in which the city was flush with wealth, Mann saw family responsibility as the cornerstone of society and believed the only value in homosexual attraction was its contribution to art. Mann expressed his own attractions through a number of his best known works, including Death in Venice, and his fiction is commonly interpreted as a catharsis from the pressures of balancing his needs against a “respectable” family life.

Though little of Mann’s adult life was spent in Lübeck, the Buddenbrooks House is a popular tourist stop. Once home to the writer’s grandparents, the house today is a small but informative museum devoted to the Manns, that explores not just their cultural impact, but the family’s broader role in the Hanseatic region. Fans of his semi-autobiographical work Buddenbrooks will delight in recreated living areas of the house, but it’s worth roaming them with Mann’s immediate family conflicts in mind. Opinions vary on whether Mann loved his infamously free-spirited Brazilian wife, Katia, or whether he quietly resented her, tolerating the marriage only for her family’s wealth and to consolidate his own position in society.

Mann’s queerest legacy, however, was his six children. The older three, Erika, Klaus and Golo Mann, were all openly gay for at least part of their lives, though Golo acknowledged it publicly only days before his death in 1994. Klaus in particular made little attempt to hide his homosexuality, much to Thomas’ disgust. He too would become an author of some note, producing works such as Mephisto and The Volcano. Despite this, he would never escape the looming shadow of his father, eventually committing suicide in Cannes in 1949. His death devastated his older sister, Erika, who had been one of his closest friends and confidantes throughout their lives. But Klaus wasn’t the only gay man close to Erika’s heart. In 1935, she escaped Nazi rule through a lavender marriage to British poet WH Auden. The marriage – and their friendship – would last until her death in 1969, 11 years after the release of a frank, but largely forgotten memoir about her father.

While the Buddenbrook House leaves the finer points of the family relationships open to interpretation, it does explore in detail the Mann family’s opposition to Hitler, and the active role they took against the Nazi propaganda machine. Their exile from Germany and passion for social justice is shared with another of Lübeck’s famous sons, Willy Brandt, whose former home is located just a few blocks away in Konigstrasse. There’s no queer content to be found at the Brandt museum, but it’s free and offers keen insights into Germany’s return to democracy and unity in the 20th century. The interactive displays cover Brandt’s life, his political career including his fight against Nazism, his expulsion to Norway during World War II, and his roles as a member of the Bundestag, mayor of Berlin, and eventual Chancellor of West Germany from 1969 to 1974. Brandt’s devotion to social justice would continue until his death in 1992, calling for increased development for the Third World and playing an active part in Germany’s reunification.

Much of Lübeck’s real charm, however, lies in its medieval architecture. Visitors are greeted by the Holstentor, the symbol of Lübeck dating back to 1464. Next to it, on the river facing Lübeck, horror buffs may recognize a row of former salt warehouses, which served as the onscreen home of Nosferatu in gay filmmaker FW Murnau’s 1922 film. For visitors with a fear of puppets, the terror continues around the corner at the Theaterfiguren Museum, the world’s largest display of stage puppets.

But no visit to Lübeck is complete without sampling the city’s sweetest export: some marzipan from Niederegger, located just behind the medieval town square. Whether the city’s claim to have invented it holds true or not, marzipan has become an inseparable part of its identity, even prompting Thomas Mann to write; “I can be sure that my Lübeck roots and Lübeck marzipan will be brought up, but I cannot feel insulted, because it is a most delicious substance.”

By all accounts, he should know. Having served up its trademark sweets since 1806, Niederegger immortalises the writer with a marzipan statue in its museum, claiming to this day that as a young boy, Mann was one of their most insatiable customers.

To plan your visit to Lübeck, visit luebeck-tourism.de

Hamburg is about an hour’s drive southwest of Lübeck. For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Hamburg, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

Berlin is a three hour drive southeast of Lübeck. For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Berlin, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

Leipzig is a four hour drive southeast of Lübeck. For the most up-to-date travel information on gay Leipzig, see our City Guide, Listings Guide, Events Guide and Activities Guide.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra