Queers are leaving Church Street to go dancing on Queen West. Gays, lesbians and straight people are partying in the same clubs. Cutting-edge lighting displays are synched to music.

The transitory nature of the nightclub world can make it easy to forget that many of the movements and innovations touted as ground-breaking by promoters and club owners nowadays probably already happened.

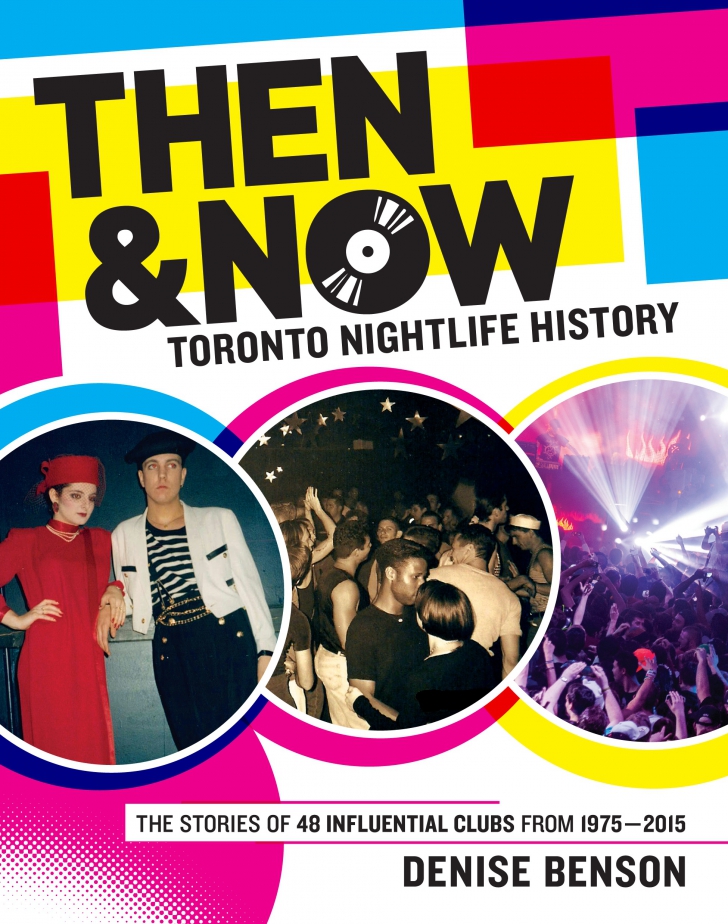

That point underlies much of Toronto music journalist Denise Benson’s book Then & Now: Toronto Nightlife History, which chronicles the evolution of clubbing in the city from the late 1970s to the present.

Published by Three O’Clock Press, the book expands upon a series of nightclub histories which Benson wrote for the now-defunct alt-weekly The Grid. She interviewed the club owners, DJs, promoters, bartenders and other assorted Toronto nightlife characters that made nightspots such as The Edge, Stages, Boom Boom Room, Bamboo, Industry, Footwork and Circa — among others — must-attend destinations.

“We always think our generation is the one that changed things,” Benson tells Daily Xtra. “But as someone who started doing queer nights in the late ’80s in Toronto, I saw all these people doing amazing, cool stuff that absolutely influenced what I did whether I knew it or not. Making those links between generations and scenes and clubs was definitely part of the joy of this project.”

In all, Benson’s book profiles 48 clubs. Each was chosen for a focus on music programming as well the sense of community fostered among a diverse clientele. It was not uncommon for clubs popular with queers — such as Stages, Boom Boom Room, Chez Moi and Domino Klub — to attract straight partiers.

Although monthly parties such as Big Primpin, Yes Yes Y’All, Business Woman’s Special, Hotnuts and Benson’s Cherry Bomb aim to draw inclusive, queer-friendly audiences, they are not generally part of a club’s wider programming.

At one time, it was more common for Toronto clubs to host different demographics on different nights of the week. Today, Benson sees more clubs segregated based on gender, ethnic and sexual orientation as rising costs force promoters to play it safe.

Higher property values mean building owners are more inclined to sell nightclub spaces to condo developers. Thus, Then & Now also follows a geographic movement of nightlife from Yonge and St Joseph in the ’70s and ’80s, down to Richmond Street and further west in the ’90s and ’00s.

“What’s going on now boils down to the economics,” she says. “One of the byproducts of all the gentrification, which is a core theme in the book, is that it’s more expensive to open venues in downtown Toronto. You have to find ways to make money to support them so that means less risks can be taken.”

She cites the Bathurst Street club Coda, the Electric Island music series and the DIY music scene on Geary Lane as current examples of spaces that attracte mixed crowds, but they are exceptions. As the book points out, clubs such as Go Go or Boom Boom Room were considered just as gay as they were straight.

“There’s been a real movement to the higher cover charge, VIP and bottle service. It’s not about music or community — it’s about seeing and being seen,” she explains. “While clubs have always had an element of seeing and being seen, a lot of clubs have had a lot more fun with that idea and allowed people to be creative, be themselves and be characters and interact with one another.”

The commercial success of EDM and so-called “bro-step” that caters to lowest-common-denominator male aggression is also distressing. However, the swift reaction from bookers, agents, DJs and even record sellers to a homophobic rant by Lithuanian producer Ten Walls that effectively killed his career is perhaps a sign many do not want to tolerate the erasure of dance music’s gay, black and Latino roots any longer.

“Bro! Bro! Bro! It’s like bullshit! Bullshit! Bullshit,” says Benson. “It’s just an excuse for rudeness. Instead of calling someone a douche, I’ll call him a bro and it signifies the same thing. As someone whose life, career and passion is so closely connected to house music and electronic music, that trend is agonizing.”

The success of producers such as Kaytranada and Jamie xx and rappers such as Kendrick Lamar and J Cole signal that listeners are craving music with more substance. The question now is if more club owners and promoters will appeal to these audiences.

“Toronto is a city where there is no one sound. There is no one take on any genre, so the plus side is people have a lot of space to innovative,” she says. “There is the formulaic stuff that serves as entry points for people. New people will come in through this wave of EDM and some will go deeper into it. We’re due for a new generation. There will be a next cycle.”

(Then & Now is now available everywhere.)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra