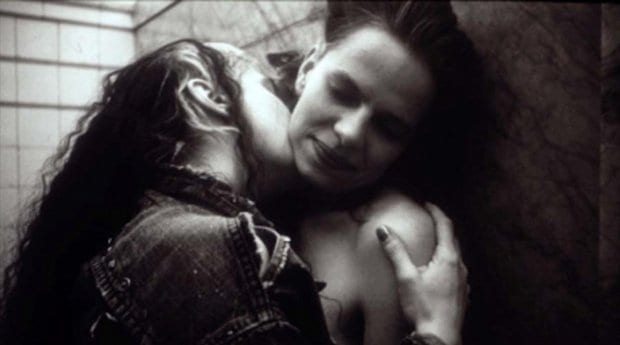

In a black and white photograph, a woman wearing nothing but a leather jacket lies flat on her back, hands tucked behind her head. Another woman, clad in a leather armband and black bra, smiles down at her as she reaches out to stroke her naked crotch.

They’re on the floor of what appears to be a barn or a warehouse, so filled with shadows it’s difficult to tell.

Although this image may not sound like a particularly subversive scene, it caused an uproar in 1990 when it was mounted at a Vancouver gallery alongside 99 other explicit photographs of lesbian sex.

The exhibition was called Drawing the Line, and female viewers were invited to write on the walls around the photographs to declare for themselves where they would draw their own lines, how far was too far.

Nothing like it had been done before.

This summer Vancouver’s Queer Arts Festival will revisit the exhibition and reflect on its impact around the world and on broader discussions of sex and sexuality. The festival’s theme is “Trigger: Drawing the Line in 2015” and will showcase work from artists across Canada that pushes boundaries and buttons, just as the original Drawing the Line did 25 years ago.

“I wanted to ask the artists, ‘What sets you off?’” says artistic director SD (Shaira) Holman. “Where do you draw that line? And how is that different from [1990]? How is it similar?”

Holman was studying at Emily Carr University when Drawing the Line first opened, and had never seen anything like it.

“At the time I was not familiar with interactive work in that way,” she says. “It really affected me, what they were doing — asking rather than telling.”

When Holman recently discovered that the Oxford Dictionary of Art singles out Drawing the Line as the quintessential example of LGBT art, she knew she wanted to make it a central part of this year’s festival.

First she had to convince the original artists to get on board.

Art, pornography and censorship

Drawing the Line was created by the artist collective Kiss & Tell — three women (Persimmon Blackbridge, Lizard Jones and Susan Stewart) with a shared passion for art and political activism.

The collective formed in the late 1980s, stemming from a discussion group for women interested in talking about sex and art.

“We were trying to sort out what we thought about censorship,” recalls Stewart, who is now the dean of the faculty of culture and community at Emily Carr University. “Most or all of us were artists who were in one way or another making images that were not PC.”

Stewart had dropped out of three art schools in three different provinces before eventually landing in Vancouver. The graphic representation of sex and less-than-politically correct content in her art was never received well by her instructors.

“It was okay to do nude life drawing in art school. It wasn’t okay to do what I was doing, which was invent scenarios and have your friends act them out and shoot them in photography,” she says.

That didn’t stop her from sharing her art with the discussion group.

“I showed that work there and got a lot of support for doing it, and that was the first time ever,” she says.

It was at this time that Angles, one of Vancouver’s early gay and lesbian community newspapers, published an issue that featured photos of lesbian sex, including BDSM imagery. Although Stewart describes the pictures as “pretty mild by today’s standard,” they provoked a strong reaction within the city’s queer and feminist communities. Some people celebrated the images, while others said they were exploitative and promoted violence against women.

“Some people were really outraged,” says Stewart, who remembers stacks of the magazine being thrown into dumpsters. “Our group talked about it and said this is censorship.”

Stewart, along with Blackbridge and Jones, formed Kiss & Tell to address the issue.

“We were saying, ‘Everyone’s saying they know what’s exploitative and what’s not, what images there should and shouldn’t be,’ but no one had even seen it!” says Jones, now the artistic director of Kickstart Disability Art.

A lot of women at the time had never even seen pornography, she adds.

“What if we made those images and put them in a row and people could draw their line?” she says, describing the idea behind Kiss & Tell’s original plan.

A flashpoint for the community

With Stewart as photographer and Blackbridge and Jones as models, Kiss & Tell produced a series of intimate photos that started out “easy to look at” and became progressively more graphic and hardcore. The artists provided black markers to gallery visitors so they could literally draw a line where they felt the photos had gone too far.

But something surprising happened. Women used words instead to describe their reactions, and their limits.

“There was line drawing, but mostly what people wanted to do was write on the wall,” Jones says.

Kiss & Tell asked that only women write on the walls, that men write their comments in a large book that was present.

“It exceeded our expectations. What we wanted was debate, dialogue, and conversations,” Stewart says. “We wanted this show to be a flashpoint for getting these issues out into the community.”

The initial exhibit took place in 1988 and featured 30 photographs. It wasn’t until two years later, when Vancouver hosted the 1990 Gay Games, that a full version of the exhibit was launched with 100 photographs. Kiss & Tell then spent several years touring the show across Canada and internationally.

“I noticed in different cities, different images would really push buttons,” Stewart says. In Vancouver the BDSM scenes caused the greatest stir, while in Melbourne, Australia, a photo of two women having sex while a man watched generated the most reaction.

“Those images just got blacked out [with marker]. Women were furious about them, whereas in Vancouver they didn’t really cause too much of a ripple.”

Drawing the line in 2015

Although Kiss & Tell’s members are proud of their work, they expressed some reticence when QAF approached them about the idea of centering this year’s festival around their exhibit.

“I really resisted for three months,” says Stewart, who feels that today, given the public’s constant exposure to sex and pornography, the images will seem dated. “It would feel too staged at this point.”

Jones had reservations too, initially.

“Gender is really different now,” she says, noting that Drawing the Line’s original format — where women write on the wall and men write in a book — doesn’t fit with understandings of gender today.

However, upon considering the original exhibit in a historical context, Kiss & Tell agreed that remounting some of the art for a 21st century audience makes sense, especially since many of the collective’s original concerns about censorship and art persist to this day.

“People are still doing that. People are still drawing the line where it’s not okay to cross,” says Holman, citing, for example, public outcry over sexual content in Raziel Reid’s award-winning young adult novel, When Everything Feels Like the Movies.

“I think that people are going to get very worked up about what we’re doing,” she adds.

Triggers and warnings

In keeping with the spirit of Kiss & Tell, festival organizers have invited artists who challenge public perceptions of “acceptable” art and imagery to join this year’s discussion.

Queer performance artist Coral Short will present a video curation called Trigger Warning featuring a series of short films, each containing a range of potential triggers, from sex to claustrophobia to meat consumption.

Short says the films contain a “wide array of things that make you feel odd.” She also says they’re thought-provoking.

“It’s the most intense bill I’ve ever made in my life, hands down.”

Short says her goal is not to harm her audience; she wants a “culture of comfort” in the theatre, an environment in which people can leave and come back if a film is upsetting them. But, she says, it’s important for art to take viewers out of their comfort zone.

“I think it’s really daring and really risky and exciting for the Queer Arts Festival to embrace this trigger warning [theme] because it brings up huge amounts of conversation,” she says.

Even if terms like “trigger warning” had not yet been invented 25 years ago, conversations like those that Short and other artists hope to generate this summer follow directly in the tradition of Drawing the Line.

“It wasn’t just a beautiful erotic art show,” Jones says. “It was about people saying something and women saying something, in a field they were never allowed to.”

During the exhibition’s Vancouver showing, before Kiss & Tell commenced its world tour, the photograph of Jones and Blackbridge half-naked in the shadow-filled barn or warehouse elicited many comments on the gallery wall.

“Some of these images make me uncomfortable but I want to look, I can’t draw lines on it,” one woman wrote. “We’re always vulnerable to violence whether we stay in line or not, so I’m going to look and feel what I feel, not just what ‘good girls’ are supposed to feel.”

The 2015 Queer Arts Festival runs July 23 to Aug 7 at the Roundhouse Community Centre, 181 Roundhouse Mews, in Vancouver. For a full schedule of shows and events go to queerartsfestival.com.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra