With the recent news that 1990s TV shows Twin Peaks and The X-Files are being revived, it seems we may have reached the end of ’80s nostalgia. Every movie, every song, every cartoon, every weird fashion from that era has been rebooted and recycled, except for one vital genre: the AIDS novel.

“I don’t want to read a book with AIDS in it,” I was recently told, “It’s too depressing.” This was not the first time I’ve heard such a thing and, while understandable, it’s a tragedy that works of genius like Paul Monette’s Borrowed Time or Dale Peck’s Martin and John might be slipping from history because reading about AIDS nowadays is considered “a downer.”

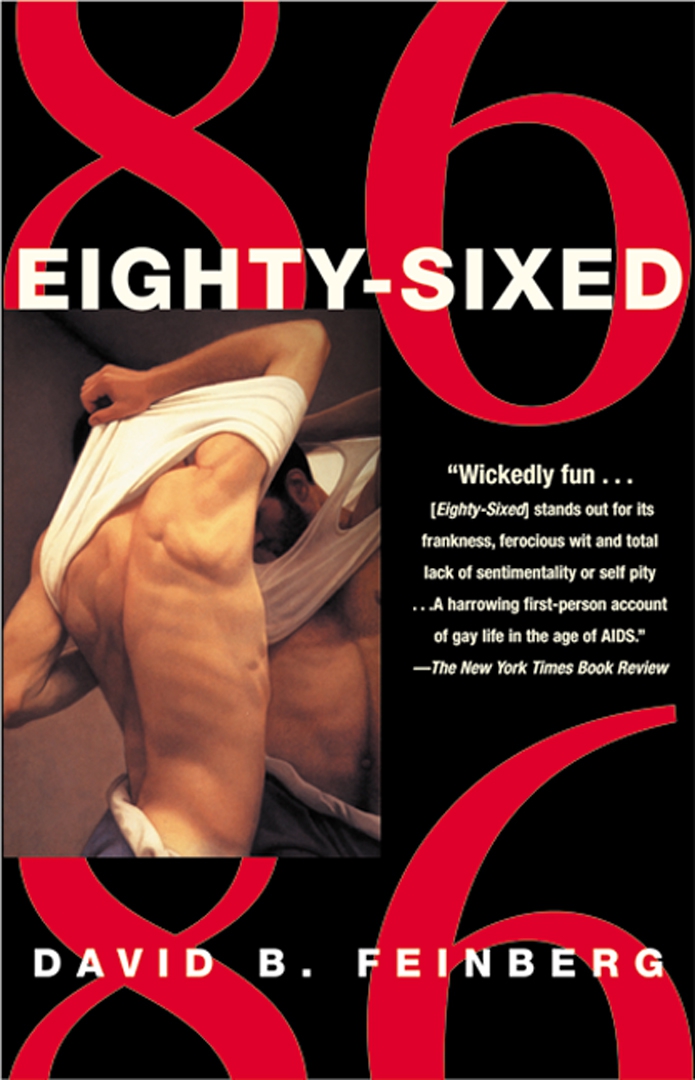

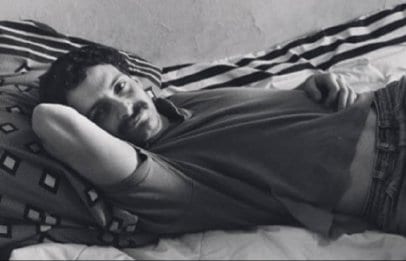

But what if the AIDS novel was funny? What if it was sharp and caustic and contemporary, even now? There’s still room for David B Feinberg on our bookshelves. He was a writer and activist whose first novel, Eighty-Sixed, achieved the dual feat of perfectly capturing both the heady days of gay liberation and freewheeling sexuality of New York in the ’70s and early ’80s and the later horrors of the “gay plague” that engulfed his community of friends and lovers while being ignored by the rest of America. And it’s all somehow hilarious.

“In an absurd world,” he said of his work, “humor may be the only appropriate response.” As a chronicler of “Safe Sex in the Age of Anxiety” in his books, columns and pieces for the daring Diseased Pariah News, Feinberg tackled the pressing questions of how to cruise when you’re losing your peripheral vision or how to disclose your positive status over Thanksgiving dinner (“I’m sorry I contracted the deadly HIV virus, Mother, and I promise I won’t do it again”).

“David had a talent for making everyone feel as uncomfortable as he did,” wrote John Weir in his 1995 POZ magazine eulogy for Feinberg. “His three books, Eighty-Sixed, Spontaneous Combustion and Queer and Loathing are filled with his acid, delirious, silly, irresistible brand of humor. He will be remembered as an AIDS activist and a very inventive, charming and unrelenting flirt.”

In his two novels, Feinberg’s thinly concealed version of himself jokes through funerals and injustices galore. He’s horrified when he gets his photo taken while marching in a New Jersey AIDS protest–not because he’s been outed in the newspaper but because people might think he lives in New Jersey. He contrasts the fury of being arrested at an Act-Up demonstration at a Catholic church with the boredom of the activists waiting in their holding cells: “We discussed the typical New York topics: homoerotic art, apartment rents, the pros and cons of outing, the size of various activists’ members and where they might be found at any given time.”

Feinberg’s processing of anger through glibness didn’t work for everyone. Reviewing Eighty-Sixed in the Los Angeles Times, author Daniel Curzon wrote, “The book seems to have been written to show that a superficial, snotty man can remain true to himself throughout the AIDS crisis by continuing to be superficial and snotty . . . If this book was written to make readers think a lot of vacuous gay men have gotten AIDS so good riddance, then it succeeds admirably.”

But Curzon’s ironically superficial and snotty review misses the point — Feinberg was railing against the public’s desire to either hide the AIDS crisis from view or, when it couldn’t be avoided, to focus on “innocent victims” like the young hemophiliac Ryan White. The characters in Feinberg’s books are no innocents yet they still deserve life, love and respect and will fight for it. After brunch, of course.

In the essay collection Queer and Loathing, published a month after his death in 1994 at the age of 37, Feinberg writes, “Humor is a survival tactic, a defense mechanism, a way of lessening the horror. I would probably go literally mad if I had to deal with AIDS at face value.” In the decades since Feinberg’s work was published, the overwhelming terror of the AIDS era has thankfully eased but it would be a crime to see its lessons, its stories and its heroes also fade from our consciousness. If the 1980’s synthpop songs can be sampled again and again and its tiny plastic Transformers toys can be recycled into blockbuster movies, surely there’s room to keep Feinberg’s spirit of ’86 alive.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra