James Stewart was many things to many people.

Memories of Stewart, who died Dec 3 after succumbing to multiple myeloma, change with each person you talk to, although all describe him as a multifaceted person who was humble and kind.

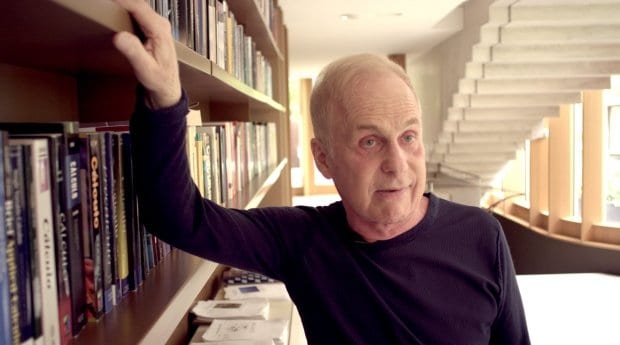

Stewart was a brilliant mathematician. He wrote textbooks that are read the world over. “He was treated like a math superstar whenever he went abroad,” brother-in-law Don Smith recalls. “People . . . would ask him for his autograph.” On the McMaster campus in Hamilton, where he taught for many years, his contribution lives on, inscribed on a building — the James Stewart Centre for Mathematics. At the University of Toronto, in the city where Stewart was born, the library at the Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Sciences is also named in his honour.

Smith, who knew Stewart from a young age, remembers him as a precocious child who was interested in everything — except sports — and always worked toward a goal. Even as he rose in the field of mathematics, Stewart still was the humble person Smith knew as a youth.

“We never really thought of him being like a Bill Gates,” Smith says. “He’s just treated as an ordinary individual who was part of the family.”

Stewart was a musician. A talented violinist, he was the concertmaster for the McMaster Symphony Orchestra and played violin professionally with the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra. “Math paid the bills, but he was very much in love with music,” Smith says. Stewart’s famed textbooks even included a sound-hole insignia on the covers, the same as those found on the body of a violin.

His home, Integral House, is a monument to his passion. Built by Canadian architects Brigitte Shim and Howard Sutcliffe in Toronto’s Rosedale neighbourhood, the home includes a concert hall that seats 150 — though it might be more accurate to say it’s a concert hall that includes a home. The concert space was Stewart’s only requirement, according to reports — he gave the architects free rein otherwise.

And Stewart was a gay man. He was out when he lived in Hamilton, a working-class town built on the edges of steel mills, in the late 1960s and early ’70s. His family knew he was gay, and it was never an issue — Smith says he was just family and that’s all there was to it.

Stewart was deeply involved in LGBT activism. According to Joseph Clement, a documentary filmmaker who is working on a film about Stewart and Integral House, Stewart brought gay rights activist George Hislop to speak at McMaster in the early 1970s, when the LGBT liberation movement was in its infancy, and was involved in protests and demonstrations until mathematics began to dominate his life. Clement says that to write his first textbook, Stewart wrote 12 to 14 hours a day, 364 days a year, for seven years.

But Stewart’s activism was near and dear to his heart. “When I was interviewing Jim, he said to me that probably the most important thing he has ever done his entire life was his work in the gay rights movement in Hamilton,” Clement says, noting that Stewart was so modest, few people know about the role he played in LGBT activism.

Stewart continued to support LGBT educational programs and charities, often by throwing fundraisers. He also threw big, lavish parties for Pride every year. The last one, coinciding with WorldPride, was a bittersweet affair attended by friends who knew it could be the last time they saw Stewart, close friend Riko Gunawan says.

These are parts of Stewart’s life, but not the sum of them. For all the accolades and achievements he earned, it doesn’t describe the man who had a family that loved him and a best friend he spoke to almost every day.

When Gunawan moved to Toronto, Stewart was one of the first people he met. “We just hit it off since then,” Gunawan says, despite their large age difference. They bonded over their shared love of classical music, going to many musical performances together. “For the last 14 years, I spoke to him every single day. The last two days is really the first time I didn’t talk to him,” Gunawan says. “It’s weird.”

Stewart even changed Clement’s life, inadvertently. When Clement was working as a landscape architect in New York City, he saw photos of Integral House under construction. “I went back to my desk and I stared at my computer screen and I said, ‘What am I doing with my life?’” Clement went back to graduate school and became a filmmaker.

In the end, Stewart was a man who faced his own mortality as few could. He planned his own wake, then decided that he wanted to attend it. “He felt that the musical lineup was so outstanding that he just had to be there for it,” Smith says. At the wake, Smith says, Stewart received standing ovations just for the act of standing up — his illness had rendered Stewart physically weak and he needed help to rise to introduce the performers.

It was appropriate that he held his own send-off in Integral House — a dream home that he got to live in for only six years. Gunawan is happy that Stewart got those years: “He had a great life, and he had accomplished everything that he had wanted in his life.”

Smith says that Stewart wanted his beloved home to be used as a performance space, a goal Smith hopes can be fulfilled.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra