It seems like a small accident that Stephen Andrews is alive. Diagnosed with HIV in 1985, he was part of a generation of gay men that was very nearly wiped out. Watching those around him drop like flies (1993 alone saw him attend 15 funerals, including that of his partner, writer Alex Wilson), he not only survived, but continued to produce work.

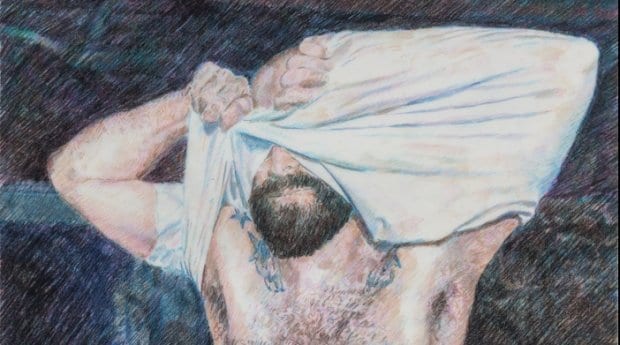

Despite the darkness of his subjects, Stephens’s art often takes a slightly playful approach to melding documentary elements with current technology. Facsimile, from 1991, repurposed portraits of men who had died by sending them through a fax machine (cutting edge for the time). The Quick and the Dead, from 2004, rendered video stills from the Iraq War in crayon.

This time he brings a new show to Paul Petro Gallery, which melds an educational series he created for CATIE (Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information) and a selection of abstract works. Xtra caught up with him to chat about the exhibition and how living with HIV for half his life continues to inform his work.

Xtra: This show includes pieces you produced as part of a project for CATIE around “risk communication” for gay men relating to HIV. What were you trying to achieve with those works?

Stephen Andrews: CATIE had approached a group of us — including Daryl Vocat, Julian Calleros and myself — to develop a visual language for a new education program. Each of us was trying to reach different groups in the community and spread specific, recent information about HIV. Essentially, the crisis is mostly being driven by people who are positive but don’t know. Someone is at their most infectious shortly after they seroconvert. We want to encourage people to get tested. Positive people on medication and using condoms are unlikely to transmit the virus. This is all information that people across different communities aren’t necessarily aware of, so we were working to disseminate it in a sex-celebratory way that helped to combat stigma and blame.

A lot of your works from the 1990s focused on HIV. It seems like you took a break from dealing with it to focus on other issues, such as the Iraq War, but came back to it more recently.

Unfortunately, one doesn’t get a break from HIV. There were a lot of gains made in the fight against HIV during the 1990s, so I felt I could focus my attention on other political issues. But I still helped friends and acquaintances that were seroconverting, making treatment choices and accessing the new services available to them. Even with the medications, a diagnosis is a very fraught emotional experience, so shepherding someone through the early stages of living with HIV is an important thing to do.

There’s also a pair of works in the show looking at the “butterfly effect,” the idea that very small actions can have huge cascading consequences.

My interest in chaos theory stems from a few personal stories that could have had very different outcomes had the slightest action been different. I guess you could extend that idea to the day someone learns they’re positive. What a difference a day makes. The Butterfly Effect paintings play with those ideas in a formal way, moving a series of different-coloured shapes on a canvas to produce completely different abstract paintings.

The exhibition is completed with a group of paintings about describing light. How do you see these different bodies of work relating in an exhibition?

For the most part, my work is about a life lived. I’ve been living with HIV since the mid-1980s, so that experience colours how I see the world. Everything I put into a work of art comes from the world as I see it. My subjects could come from either the day’s headlines or simple encounters with people. Light is a metaphor for life, so my work in the simplest terms is about life, I suppose. I am reminded every day, twice a day, it should never be taken for granted.

Possible Outcomes, featuring the work of Stephen Andrews, runs Fri, Oct 10–Sat, Nov 8 at Paul Petro Gallery, 980 Queen St W.

paulpetro.com/exhibitions

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra