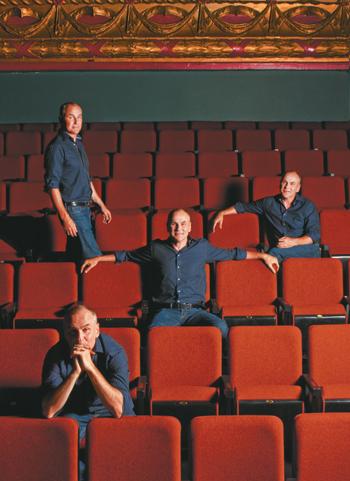

MacIvor's newest play, His Greatness, opens at Toronto's Factory Theatre on Thursday, Sept 22. Credit: Ryan Faubert

“Things move in cycles,” actor, playwright and producer Daniel MacIvor tells me as we chat on the fire escape at Toronto’s Factory Theatre. It is the day before rehearsals are to begin for his latest play, His Greatness.

MacIvor has become synonymous with the do-it-yourself aesthetic that typified his work with the seminal Augusta Company in Toronto, where he collaborated with Don McKellar, Daniel Brooks and the late, great Tracy Wright. The story of his journey from those experimental roots is one of an eminently intuitive, endlessly curious artist following his instincts down the many rabbit holes of his own career.

After helping to kick-start one aesthetic movement with the Augusta Company, MacIvor created a series of one-man shows, with Brooks directing and Sherrie Johnson producing. This work, with the company da da kamera, included hits such as Monster, Here Lies Henry and House and earned MacIvor national and then international recognition. MacIvor’s lacerating wit, transmitted through the razor-sharp precision of Brooks’ directorial minimalism, exploded the toxicity burbling under the veneer of polite Canadian society. It brought to mind the words of British theatre critic Kenneth Tynan: “Not content with holding the audience in the palm of his hand, he goes one further and clenches his fist.”

MacIvor shifted artistic gears again in the mid-2000s, deciding to take a crack at the well-made play.

“My mother said, ‘Can you please write a play that I would like?’” he says.

Since closing da da kamera in 2007, he has created a series of such plays. In his review of one of these works — Communion, a psychoanalytic dramatic-comedy that played the Tarragon Theatre in 2010 — Toronto Star theatre critic Richard Ouzounian wrote of “a kinder, gentler Daniel MacIvor.” For MacIvor, though, this apparent shift from more overtly subversive fare comes down to a consideration of his audience: “I’m always conscious of the audience. Every play is not for everybody.” And it doesn’t seem likely, incidentally, that all of his well-made plays would have pleased his mother.

An attempt to synthesize the aesthetics of the Augusta Company and da da kamera with his more recent plays is an idea that occupies space in MacIvor’s fertile mind. He elaborates: “I think narrative is very important. There’s a way to use the elements of the well-made play and the elements [of] DIY… it requires rigour, but I think it’s possible.”

His Greatness is based on a notorious encounter between Tennessee Williams and a local hustler during the 1980 Vancouver Playhouse production of Williams’ play The Red Devil Battery Sign. Though, in MacIvor’s view, he doesn’t quite marry the many facets of his artistic practice with His Greatness, he does promise, “It’s absolutely informed by the other work that I’ve done.”

MacIvor takes on the role of the Williams character’s put-upon assistant in this production. Given his perspective as both playwright and performer, I ask MacIvor who was, to his mind, the real Tennessee Williams.

“I tend to believe he was all the things that he presented himself to be, struggling with the modern world… and how he was supposed to fit into it. His Greatness makes a case for the importance of theatre, that it’s essential.”

MacIvor is a man thoroughly acquainted with greatness, continuing to challenge our expectations and interrogate his own identity as an artist. Perhaps in the end, this is his greatest gift to his audience: he keeps us guessing about which direction he will take, which questions he will pose and where his curiosity will lead us next.

“Rightness is irrelevant,” he concludes. “It’s authenticity and presence and generosity and service,” to which he adds modestly, “I work at those things; I don’t master them.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra