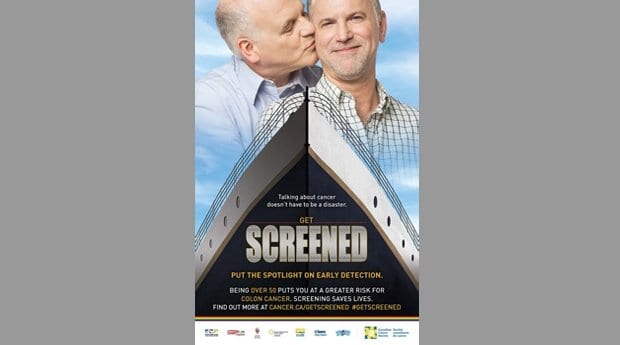

A sample ad for the Get Screened program. Credit: Get Screened

Talking to a doctor about your sexual organs is uncomfortable for many people. But for LGBT people, asking questions and getting examined can open up a whole host of embarrassing, and scary, issues.

The Canadian Cancer Society (CCS) believes that fear causes queer people to avoid being screened for treatable cancers, thereby endangering their lives. The organization is launching a new program called Get Screened to encourage LGBT people to screen for colon, breast and cervical cancers early while also training doctors to approach LGBT health issues in a sensitive way.

“When working with LGBT clients, many have faced barriers to care in the past and may not absolutely be comfortable about discussing issues of sexual orientation or gender identity,” says Ed Kucharski, a physician at the Sherbourne Health Centre and a member of the Get Screened steering committee. “Often there’s sensitivity around discussing cancer screening because they’re in sensitive parts of the body, such as breasts or the cervix.”

A targeted campaign has already distributed quirky, romance-movie-themed flyers and posters to doctors’ offices and LGBT organizations, while print ads are being placed in select newspapers and on public transit.

The CCS is helping to train health ambassadors in the LGBT community to help start the discussion on cancer screening.

“We have a cross section of all LGBTQ communities of different races and abilities, and they go out and talk to their friends and families, so if someone is experiencing a barrier to getting screened, they can talk about it with their friends,” says Arti Mehta, a coordinator of the Get Screened initiative.

The message is clear: cancer doesn’t care if you’re gay, straight, bi or trans — everyone over 50 should be tested regularly for colon cancer. Women over 50 should get regular mammograms to check for breast cancer. These types of cancers, if caught early enough, can be successfully treated, and the tests are covered by provincial health plans.

Not only concerned with empowering patients, the campaign looks to educate doctors and other healthcare providers about LGBT issues.

“Lesbian women are still told that they don’t need pap tests, and we know that’s completely untrue,” Mehta says. All women who have ever had sex, even once, need to have regular pap smears to check for and prevent cervical cancer.

A trans man, however, may not feel comfortable in a gynecologist’s waiting room or coming out to a technician who performs a mammogram.

“Some providers will very coarsely say, ‘Everybody needs a pap who has a cervix’ and try and encourage a patient to get a pap smear for screening for cervical when they might not be ready,” Kucharski says. “I look at is as kind of a journey you have with a patient in developing trust and talking about the risks and benefits to screening.”

The CCS is compiling research on best practices in LGBT health to help train practitioners, but there is not a lot of conclusive research on treatment and screening options for trans people.

“We don’t have a comprehensive evidence-based approach for how hormones and surgeries affect cancer and cancer screenings, but we’ve compiled as much information as is out there for service providers and trans people around how to get screened and how often,” Mehta says.

The Get Screened materials were developed with the support of the Public Health Agency of Canada, but its ongoing operations are funded out of donations to the Canadian Cancer Society. A fundraiser for the program, Cancer Is a Drag, will take place Nov 7 to 9 at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre.

Learn more about cancer screening for LGBT people at cancer.ca/getscreened.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra